A Moment Big Question

A SOUNDTRACK OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE

A musical journey through time

and space charting the breadth of the Jewish soul

A Moment Big Question

A SOUNDTRACK OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE

A musical journey through time

and space charting the breadth of the Jewish soul

One of the great powers of music is that it brings people together. It’s one of those rare realms where people of varying beliefs and proclivities can find common ground. Take, for example, the late Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia, who strongly disagreed on matters of jurisprudence but bonded and became dear friends over their shared love of opera. With unity in short supply, and with sheer delight, Moment embarked on an ambitious year-long undertaking—talking with a diverse array of musicians, scholars and music lovers—to gather together music with Jewish significance. The result is a rich tapestry of genres, evoking the breadth of Jewish spirituality, culture, experience and history. We’ve also created playlists, so your ears can feast on the beauty and healing power of these Jewish and Jewish-inspired sounds.

This “Big Question” is a collaboration between Moment and the Milken Archive of Jewish Music.

Interviews by: Diane M. Bolz, Suzanne Borden, Sarah Breger, Brianna Burdetsky, Nadine Epstein, Dan Freedman, Lilly Gelman, Dina Gold, George E. Johnson, Leslie Maitland, Ellen Wexler, Amy E. Schwartz, Francie Weinman Schwartz and Laurence Wolff.

featuring:

WHAT IS JEWISH MUSIC?

Jewish music is modern and ancient, sacred and secular, communal and personal, universal and particular. Although there are few clues as to what it sounded like in ancient times, we know that music formed an essential part of ritual and daily life in early Jerusalem. Today, Jewish communities around the world showcase an astonishing diversity of musical styles and practices. Jewish music encompasses liturgy for the Sabbath, for the High Holy Days, and for festivals, all of which are different for the various branches of Jewish religious observance. It encompasses folk traditions from the many parts of the world where Jews have lived: klezmer from Eastern Europe; Sephardic songs from the Iberian Peninsula; and Musiqa Mizrachit from Arab countries. It includes popular and theatrical music that has various connections to the Jewish experience and a particular Jewish resonance. The idea of Jewish music is inconceivable without a Jewish community, but the music itself has broad reach. There’s an old definition that Jewish music is music which is made by Jews, as Jews and for Jews. That definition is too narrow: There have long been non-Jews involved in creating Jewish music, and as we all know, the audience for Jewish music is universal.

— Jeff Janeczko, curator, Milken Archive of Jewish Music

read by song:

ADIO QUERIDA

ANA EL NA

ARBA BAVOT / ALTER REBBE’S NIGGUN

ARVOLES LLORAN POR LLUVIAS

AVINU MALKEINU

AVODAT SHABBAT

BABY MOSHE TAKEN FROM THE WATER

BIENVENUE/ABIADI

CANTATA OF THE BITTER HERBS

CUANDO EL REY NIMROD

DEFIANT REQUIEM

DER GOLEM

DIE WEISE VON LIEBE UND TOD DES CORNETS CHRISTOPH RILKE

DI ZUN VET ARUNTERGEYN

ESHET CHAYIL

ESTRO POETICO-ARMONICO

EVENING OF ROSES

FANFARE FOR THE COMMON MAN

HATIKVAH

HAVA NAGILA

HIGHWAY 61 REVISITED

IF I HAD A HAMMER

IF I WERE A RICH MAN

IT AIN’T

NECESSARILY SO

JERUSALEM OF GOLD

KADDISH

KOL NIDRE

LIGHT ONE CANDLE

LITHUANIA

MAOZ TZUR

MY YIDDISHE MOMME

OLAM CHESED YIBANEH

OVER THE RAINBOW

PSALM 136

QUARTET FOR THE END OF TIME

READING SHALOM ALEICHEM

RHAPSODY IN BLUE

RIDE ‘EM JEWBOY

RIVERS OF BABYLON

ROZHINKES MIT MANDLEN

ROZO D’SHABBOS

SCHELOMO: RHAPSODIE HÉBRAÏQUE FOR VIOLONCELLO

SHALOM ALEICHEM

SHEMA

SHIVITI (HAVAYA)

SIM SHALOM

SNOW

ST. MATTHEW PASSION

SYMPHONY NO. 13 IN B FLAT MINO (OP 113) BABI YARDAGES

SYMPHONY NO. 1 IN D MAJOR

SYMPHONY NO. 3 KADDISH

SZOL A KAKAS MAR

TZUR MISHELO AKHALNU

WE ARE A MIRACLE

WHO BY FIRE

WOMEN OF VALOR

YA LGHADI ZERBAN

YOU ARE THE ONE

YOU WANT IT DARKER

Have a suggestion of an essential Jewish song we forgot?

Tell us about it here!

One of the great powers of music is that it brings people together. It’s one of those rare realms where people of varying beliefs and proclivities can find common ground. Take, for example, the late Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia, who strongly disagreed on matters of jurisprudence but bonded and became dear friends over their shared love of opera. With unity in short supply, and with sheer delight, Moment embarked on an ambitious year-long undertaking—talking with a diverse array of musicians, scholars and music lovers—to gather together music with Jewish significance. The result is a rich tapestry of genres, evoking the breadth of Jewish spirituality, culture, experience and history. We’ve also created playlists, so your ears can feast on the beauty and healing power of these Jewish and Jewish-inspired sounds.

This “Big Question” is a collaboration between Moment and the Milken Archive of Jewish Music.

Interviews by: Diane M. Bolz, Suzanne Borden, Sarah Breger, Brianna Burdetsky, Nadine Epstein, Dan Freedman, Lilly Gelman, Dina Gold, George E. Johnson, Leslie Maitland, Ellen Wexler, Amy E. Schwartz, Francie Weinman Schwartz and Laurence Wolff.

featuring:

WHAT IS JEWISH MUSIC?

Jewish music is modern and ancient, sacred and secular, communal and personal, universal and particular. Although there are few clues as to what it sounded like in ancient times, we know that music formed an essential part of ritual and daily life in early Jerusalem. Today, Jewish communities around the world showcase an astonishing diversity of musical styles and practices. Jewish music encompasses liturgy for the Sabbath, for the High Holy Days, and for festivals, all of which are different for the various branches of Jewish religious observance. It encompasses folk traditions from the many parts of the world where Jews have lived: klezmer from Eastern Europe; Sephardic songs from the Iberian Peninsula; and Musiqa Mizrachit from Arab countries. It includes popular and theatrical music that has various connections to the Jewish experience and a particular Jewish resonance. The idea of Jewish music is inconceivable without a Jewish community, but the music itself has broad reach. There’s an old definition that Jewish music is music which is made by Jews, as Jews and for Jews. That definition is too narrow: There have long been non-Jews involved in creating Jewish music, and as we all know, the audience for Jewish music is universal.

— Jeff Janeczko, curator, Milken Archive of Jewish Music

read by song:

ADIO QUERIDA

ANA EL NA

ARBA BAVOT / ALTER REBBE’S NIGGUN

ARVOLES LLORAN POR LLUVIAS

AVINU MALKEINU

AVODAT SHABBAT

BABY MOSHE TAKEN FROM THE WATER

BIENVENUE/ABIADI

CANTATA OF THE BITTER HERBS

CUANDO EL REY NIMROD

DEFIANT REQUIEM

DER GOLEM

DIE WEISE VON LIEBE UND TOD DES CORNETS CHRISTOPH RILKE

DI ZUN VET ARUNTERGEYN

ESHET CHAYIL

ESTRO POETICO-ARMONICO

EVENING OF ROSES

FANFARE FOR THE COMMON MAN

HATIKVAH

HAVA NAGILA

HIGHWAY 61 REVISITED

IF I HAD A HAMMER

IF I WERE A RICH MAN

IT AIN’T

NECESSARILY SO

JERUSALEM OF GOLD

KADDISH

KOL NIDRE

LIGHT ONE CANDLE

LITHUANIA

MAOZ TZUR

MY YIDDISHE MOMME

OLAM CHESED YIBANEH

OVER THE RAINBOW

PSALM 136

QUARTET FOR THE END OF TIME

READING SHALOM ALEICHEM

RHAPSODY IN BLUE

RIDE ‘EM JEWBOY

RIVERS OF BABYLON

ROZHINKES MIT MANDLEN

ROZO D’SHABBOS

SCHELOMO: RHAPSODIE HÉBRAÏQUE FOR VIOLONCELLO

SHALOM ALEICHEM

SHEMA

SHIVITI (HAVAYA)

SIM SHALOM

SNOW

ST. MATTHEW PASSION

SYMPHONY NO. 13 IN B FLAT MINO (OP 113) BABI YARDAGES

SYMPHONY NO. 1 IN D MAJOR

SYMPHONY NO. 3 KADDISH

SZOL A KAKAS MAR

TZUR MISHELO AKHALNU

WE ARE A MIRACLE

WHO BY FIRE

WOMEN OF VALOR

YA LGHADI ZERBAN

YOU ARE THE ONE

YOU WANT IT DARKER

Have a suggestion of an essential Jewish song we forgot?

Tell us about it here!

Shalom Aleichem

REGINA SPEKTOR

Hebrew • 16-17th century • Lyrics attributed to Safed kabbalists;

classic melody by Rabbi Israel Goldfarb, 1918

I FEEL VERY connected to “Shalom Aleichem” (“Peace Be Unto You”). This song is sung every week as Shabbat begins. It has a traditional melody that feels simultaneously mournful and uplifting. When I first heard it, I felt like I’d always known it. The words are so simple but deep. The song begins with “Peace be unto you, ministering angels.” I love the idea that humans can bless angels, and not just the other way around. Then the song takes on the structure of a human life in the following verses. Birth: “Come in peace;” Development: “Bless me with peace;” Death: “Go in peace.” Of course it makes sense that a nation of wanderers—persecuted, pogromed and battling anti-Semitism—still would wish to be blessed with peace, that most deep and eternal of Jewish dreams, being dreamed daily by most of us wherever we are.

Regina Spektor, a Grammy-nominated singer-songwriter and pianist, has released seven albums. Born in the Soviet Union, she immigrated to the United States at age nine.

Kaddish

LEONARD SLATKIN

Aramaic • 1914 • Lyrics based on the traditional Kaddish prayer; music by Maurice Ravel; part 1 of the musical composition Deux Mélodies Hébrïques

MAURICE RAVEL WAS NOT Jewish, but from my perspective, he composed a piece of music that sums up the spirit of faith beautifully. In his “Kaddish” from Deux Mélodies Hébraïques, Ravel takes the Aramaic text of the traditional prayer—usually recited at a time of mourning—and weaves a spell of extraordinary stillness, with the voice conveying a Middle Eastern-like chant. The song was written in 1914 but still retains its incredible freshness.

Leonard Slatkin is a conductor, composer and author. He is the winner of six Grammy awards and the National Medal of the Arts, among other accolades.

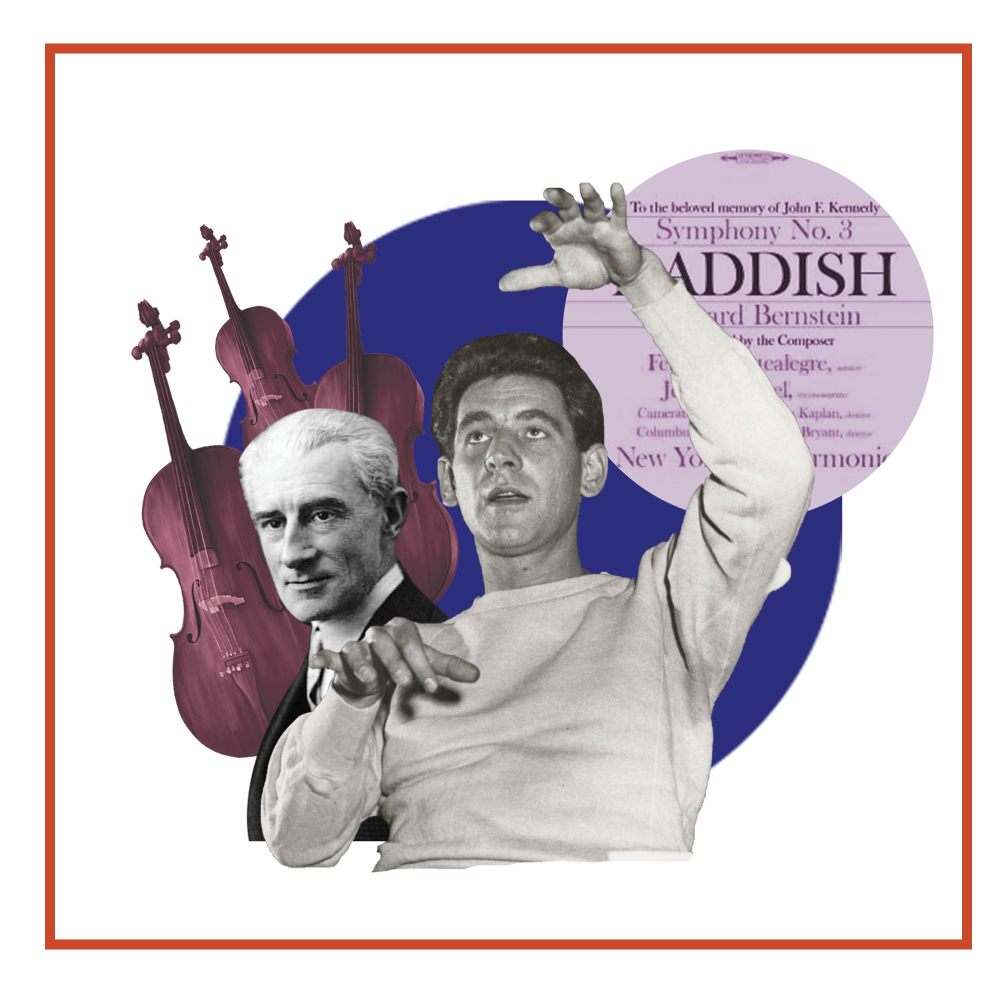

Symphony No. 3: Kaddish

JAMIE BERNSTEIN

Aramaic & English • 1963 • Lyrics and music by Leonard Bernstein

MY FATHER, Leonard Bernstein, wrote his “Symphony No. 3: Kaddish” in 1963, and dedicated it to the memory of John F. Kennedy. I experience my father’s Judaism through this music. It’s a prime example of a thread that runs through so many of my father’s compositions that express a fist-shaking at the heavens, this argument with God, this tussle with the Creator. It’s Talmudic. My father says to God, “If You’re up there taking care of us, why is everything such a mess down here, and why are we so terrible to one another?” When my father wrote this symphony he was preoccupied with nuclear annihilation, the Cold War, the aftermath of World War II and the Holocaust—with how grisly human beings could be to one another.

The piece pits tonality, a striving toward harmony, against the atonal, a tendency toward dissonance and violence. “Kaddish” includes a lot of forces—a huge orchestra, a chorus, a kids’ chorus, a soprano soloist plus a narrator. The chorus sings the Kaddish prayer in Aramaic. The narration, which he wrote for my mother to recite in English, is a contemporary argument with the Creator. It cries, “Tin God, Your bargain is tin.” And there was no question more urgent in that part of the 20th century for Jews, or anyone else, for that matter, than how to affirm life in the face of evil and suffering. My father went to the heart of the problem, an argument that is not yet resolved. At the end, the narrator forgives God for His flaws, and God forgives humankind. The final words are:

Recreate, recreate, each other!

Suffer, and recreate each other!

Jamie Bernstein, the eldest of composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein’s three children, is the author of Famous Father Girl: A Memoir of Growing Up Bernstein. A writer, broadcaster and filmmaker, she has written and performed her own narration for the symphony.

Maoz Tzur

LESLIE ODOM JR.

Hebrew • 13th century • Lyrics and composer unknown

I WOULDN’T HAVE HAD an answer to this question a year ago, but while putting together my latest holiday album, I asked my wife, Nicolette Robinson, who’s biracial—her mother is Jewish and her grandfather was a rabbi—if there were any Hanukkah songs I should include. I wanted to make sure that the Festival of Lights was represented in the album. Nicolette said that “Maoz Tzur” (“Rock of Ages”) had a beautiful melody and that the Hebrew was really lovely.

We’ve been together 12 years now. So that’s 12 Passovers, 12 Hanukkahs. Experiencing the Jewish traditions and incorporating them in my life in a meaningful way has expanded my idea of how big God is. I connect to holiness. I connect to anything that is getting at that chamber that exists within us, that exists within humanity. I call it the God chamber. It really can only be filled with a relationship with God. So I connect to the song’s beseeching of God, the begging of God to come to your aid, to come to your defense and the humility of that.

There’s a mystical, ineffable quality about music that is not meant to be spoken about. It’s meant to be heard and experienced. That’s why it exists. So my words are going to fall short, but I can feel the Holy Spirit in the “Maoz Tzur” melody and in what is happening between the notes. There will be people who listen to that Hebrew and have no idea what’s being said, but they’re still going to feel and understand the God in it. Capital G.

Leslie Odom Jr. is an actor and singer who originated the role of Aaron Burr in the Broadway production of Hamilton, for which he won a Tony Award for Best Actor in a Musical and a Grammy Award as a principal soloist on the original cast recording.

Estro Poetico-Armonico

JAMES LOEFFLER

Italian & Latin • 1724-1727 • Lyrics by Benedetto Marcello;

music adapted from the melody of “Maoz Tzur”

IN 1528, A GROUP of Ashkenazi Jews who had fled German persecution established a synagogue in Venice. Their musical repertoire featured an alternative version of the Hanukkah song “Maoz Tzur,” whose precise origins remain shrouded in mystery. Unlike the jaunty major-key version so well known today, this plaintive melody better matches the 12th-century poem itself. Spare and mournful, yet dignified by its stately, measured pace, the tune accentuates the text’s aching plea for divine deliverance in recognition of Jewish suffering.

Two centuries later, the Italian Catholic aristocrat and composer Benedetto Marcello visited the 17th-century Venetian ghetto, where he transcribed several melodies, that early “Maoz Tzur” among them. Since Jews did not regularly use written musical notation until the 19th century, Marcello’s work provided precious documentation of an oral tradition. It inspired him to assume that these Italo-German Jewish melodies constituted the lost music of the ancient Jerusalem Temple. He went on to employ the “Maoz Tzur” melody in his masterpiece, “Estro Poetico-Armonico,” a setting of the first 50 psalms for voices, with figured bass and various instrumental soloists. Marcello created a nice contrast between the ornate Italian Psalm 15 (Psalm 16 in the traditional Jewish reckoning) and the Hebrew chant, which combine in a harmonious duet in the piece’s final verse.

Every Hanukkah season, as my ears grow tired of musical parody songs and saccharine children’s ditties, I turn to this unique “Maoz Tzur” for an aural salve. Its doleful elegance provides the perfect antidote to Christmas-envy and neo-Maccabean triumphalism. Its Baroque-era reinterpretation recalls a more hopeful moment in Jewish-Christian relations in European history. And the mystery of its origins—and the story of Marcello’s own curiosity about its provenance—speak to the powerful hold of the Jewish musical past on our own imaginations today.

James Loeffler, a Jewish studies professor at the University of Virginia, curated concerts of Jewish classical music at the Kennedy Center for ten years.

Over the Rainbow

BEN SIDRAN

English • 1939 • Lyrics by Yip Harburg; music by Harold Arlen

TO MY MIND, there has never been a more Jewish-American song, in terms of authorship, thematics and circumstance, than “Over the Rainbow.” Completed in 1939, just as Hitler was planning his invasion of Poland, the song alludes to a time in America when being a Jew meant, once and for all, that one was obligated to come out of hiding, to accept the real world and build on it rather than bury one’s head in the sands of time. It was a time when Jews experienced a remarkable personal freedom for the first time and also felt a deep responsibility for tikkun olam: in Harburg’s words, “We worked in our songs for a better world, a rainbow world.”

Harburg, a businessman, lost everything in the crash of 1929. He turned to song writing as a kind of last resort and was forever grateful. Arlen, ever aware of his Jewish roots, was the son of a cantor and was a gifted pianist: He spent much of his time in Harlem learning piano from the great jazz pianists and working as house arranger at the Cotton Club. His experience of the remarkable synergy of Blacks and Jews in America helped give “Over the Rainbow” its universal sentiment, a longing for belonging in rapidly changing times.

The soaring opening of the melody of “Over the Rainbow” (“Some…where”) is a full octave leap, cantorial in its boldness and reach. At the same time, the harmonic structure of the entire song, like that of other songs being written at the time by Jewish composers such as George Gershwin and Jerome Kern, used the relative minor in the context of the major. This haunting contextualization of minor and major reminds us of that particular brand of Yiddishkeit the great Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich thought of as the Jewish penchant for “laughter through the tears,” a complex moment when darkness meets light, when the sun breaks through the clouds, if only for a moment, creating the sensation of hope, before one is plunged back into existential despair.

Ben Sidran is the author of several books on popular music, including There Was a Fire: Jews, Music and the American Dream. He holds a PhD in American studies and divides his time among academia, journalism and performing as a professional jazz musician.

Over the Rainbow

ANGELA BUCHDAHL

English • 1939 • Lyrics by Yip Harburg; music by Harold Arlen

“OVER THE RAINBOW” captures the age-old longing of an exiled people for a home. It’s no surprise it was written and composed by two Jews: Yip Harburg (born Isidore Hochberg) and Harold Arlen (born Hyman Arluck), the son of a cantor. The song captures the optimism of the Jewish people— that no matter where they have been or what they have weathered, there is another land or another time—an olam haba, a world to come—where things are beautiful and dreams come true and we are safe. When we say there is no place like home, it’s an invitation to create a home wherever you are, and an expression of the duality that the Jewish people have always had between a physical home and a spiritual home. I think it’s not a coincidence that the rainbow is a symbol of our Covenant from God. This has become my signature song. I love listening to it, and I love singing it. I sing it in the style that is closer to Eva Cassidy’s version than to Judy Garland’s. People in my community have an incredibly strong positive reaction to it. In synagogue, we sing it during the week we read the Torah portion about Noah, where the sign of the flood’s end is a rainbow.

Angela Buchdahl is the senior rabbi of Central Synagogue in New York City. She is the first woman to lead the 175-year-old Reform congregation.

Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke

PHILIP V. BOHLMAN

German • 1944 • Lyrics inspired by and based on Rainer Maria Rilke’s 1899 poem of the same name; music by Viktor Ullmann

VIKTOR ULLMANN’S “Die Weise von Liebe und Tod des Cornets Christoph Rilke” (“The Chronicle of Love and Death of the Flag-Bearer Christoph Rilke”) is stunningly beautiful music, glorious music. It’s a staged work for piano and a dramatic speaker, inspired by and based on a prose poem by Rainier Maria Rilke. It was the last piece composed for the stage in a concentration camp. Ullmann created it in Theresienstadt as he realized he’d be deported—literally composing it to accompany his own death.

Ullmann was born in 1898 in what is now the Czech Republic. The poet Rilke, who was born in Prague in 1875, was not Jewish. The poem tells the story of a romantic young recruit at the end of the Thirty Years’ War in Europe who realizes once he is in battle that war is brutality and death. It was intimately familiar to Ullmann and others in the camp, and many had memorized long parts of it. In Theresienstadt, Ullmann turned increasingly inward, toward Jewish themes. His work there became about the tremendous tragedy of the Shoah itself. It captures the powerful notion of duality in the Jewish experience: tradition and modernity, German and Jewish, sacred and secular, love and death, being outside of Jerusalem yet yearning to sing the Lord’s song in a new land.

Ullmann finished sketches for this work on September 27, 1944, was transported East ten days later and was killed in the Auschwitz gas chambers in October. While Ullmann had known the piece would never be performed in Theresienstadt, he kept working on it in the hope it would survive. Thankfully, after the war and liberation, it was rescued by the renowned author and musicologist H. G. Adler, a native of Prague who had been imprisoned with Ullmann at Theresienstadt and, like him, deported to Auschwitz in 1944. Adler survived, and in 1945 he returned to the Czech camp and found that Ullmann had given his music for safekeeping to another prisoner, philosopher Emil Utitz, who directed the camp library.

Philip V. Bohlman is a professor of Jewish history in the Department of Music at the University of Chicago. He is also artistic director of the New Budapest Orpheum Society, an ensemble in residence at the university that performs Jewish cabaret music and political songs from the turn of the 20th century to the present.

Click here to read an extended answer from Bohlman.

Arvoles Lloran

por Luvias

SARAH AROESTE

Ladino • Date unknown • Lyrics and music based on a traditional Ladino folk song and reinterpreted by Koro Saloniko in the 1940s

THIS TRADITIONAL LADINO Ladino folk song was once sung by Sephardic Jews in the Eastern Mediterranean. While it seems like a love song at first (“Trees cry for rain, and mountains for air/Just as my eyes weep for you, my love”), the chorus takes on a different meaning: “Torno y digo, ke va ser de mi/En tierras ajenas yo me vo morir” (“I turn and ask, what will become of me/In foreign lands I will surely die”). While the foreign land may refer to the heart of a lovesick boy, the words also could have been adapted from a medieval Spanish song in which a boy going off to war knew that he would not be returning home. This was his farewell to his loved ones back home.

Fast forward to World War II, when a group of Jews from Rhodes famously sang this song as they were being deported to Auschwitz. They knew that in foreign lands they would surely die. Later, a liberated group of Sephardic Jews from Salonika, Greece formed a chorus, the Koro Saloniko, in which they reinterpreted this song into the version I have come to love today. Rewriting the final verse, they sang these redemptive words: “Ven veras, veremos, en l’amor ke mos tenemos, ven mos aunaremos” (“Come and we will see together, with the love that we share, one day we will be reunited”). Ever since, this song has become an anthem for many Sephardic Jews like myself. Whether we consider our homeland to be Greece or medieval Spain, Israel or elsewhere, we are all united. No matter where we have scattered across the globe, or what hardships our communities have faced, there is a profound cultural bond that links us all.

Sarah Aroeste is an international Ladino singer, songwriter, author and cultural activist who draws upon her Sephardic family roots from Greece and Macedonia (via medieval Spain) to help bring Judeo-Spanish culture to a new generation.

Sim Shalom

RICHARD COHN

Hebrew • 1953 • Lyrics adapted from the Amidah prayer; music by Max Janowski

THE MUSIC MAX JANOWSKI composed for “Sim Shalom” (“Grant Peace”) has a kind of soaring simplicity and a very compelling spiritual narrative. The climactic passages are built in such a way that they sound out the tones of all creation. And at the same time, the cantorial writing is exquisitely detailed and incorporates the traditional nuance of the artistry that a cantor brings to the expression of a text. The way that the cantor’s singing is integrated with the voices of the congregation and with the textures of the accompaniment is as close to perfection as we hear in a piece of Jewish music.

I happened to study with Janowski, who was born in Berlin and spent most of his career as the musical director at KAM Isaiah Israel Congregation in Hyde Park in Chicago. He told me the opening motif of this piece comes straight from the Torah cantillation. To that he added the improvisational voice of the cantor, who chants with great attention to the importance of every word. Because, after all, this is not just any prayer; this is a prayer for peace, an outpouring of the heart for wholeness and for light. Wherever I’ve been involved in performances of this work, it proves to be incredibly uplifting and is received with understanding by people of very different backgrounds. Janowski dedicated his “Sim Shalom” to African-American diplomat Ralph Bunche, who won the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize for his work mediating the Arab-Israeli armistice in 1948.

Cantor Richard Cohn is the director of the Debbie Friedman School of Sacred Music at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion.

You Are the One (Reb Nachman’s Prayer)

JULIE SILVER

English • 1995 • Lyrics based on Reb Nachman of Bratslav prayer; music by Debbie Friedman

“YOU ARE THE ONE” is based on a prayer by Reb Nachman of Bratslav (1772-1810), and was edited and put to music by Debbie Friedman (1951-2011), a singer-songwriter whose songs and melodies are used by hundreds of congregations across America. “You Are the One” is one of my favorite Jewish pieces and one of the most important pieces for me on many levels.

It’s a prayer to God—Reb Nachman’s prayer. And when he says “May all the foliage of the fields, all grasses, trees and plants awaken at my coming,” it’s saying we have an imperative, that we should awaken at our being here. It is about oneness. Friedman writes the song in a major key that moves into a minor, where she’s talking. She’s made the words of this man—about the oneness of God, of nature, and of us—even softer and more accessible. It’s her magnum opus.

When I first heard Debbie sing “You Are the One” live, I knew immediately how complicated, powerful, and important this woman was. I was just embarking on my career, and I thought to myself, if this is the kind of music I could write, or be a part of, or perform, or learn from in any way, I’m there. And so the song became part of my being.

Julie Silver, an American Jewish folk musician, has released eight albums. Several of her songs and compositions are now integral works of Reform Jewish liturgy.

Arba Bavot / Alter Rebbe’s Niggun

SHLOMO GAISIN AND ZACHARIA GOLDSCHMIEDT

Traditional Hasidic Niggun • 18th century • Melody by Reb Schneur Zalman of Liadi

ONE OF THE MOST powerful pieces of Jewish music is “Arba Bavot” (“Four Gates”), probably better known as the “Alter Rebbe’s Niggun.” It was said that some Hasids once came to the founder of Chabad, Reb Schneur Zalman of Liadi, with an issue: They couldn’t understand his sefer [“book”], the Tanya. The Rebbe responded that in order to understand the teachings, they needed to learn the music that comes along with it. With melody, he said, we can unlock the gates to not just the heart but also the mind. And with that, he began to teach them this niggun [“melody”].

The fifth Lubavitcher Rebbe—Sholom Dovber Schneersohn—taught that each stanza of the niggun corresponds to a letter of Hashem’s essential name (Y-K-V-K). Similarly, these four letters correspond to the four worlds as discussed in depth in Kabbalah and Hasidism. We learn that these worlds start closer to Hashem’s revelation and ultimately work their way to where Hashem is most concealed. Our purpose is to reveal Hashem’s light in every thing and every experience and to make that reality apparent to the whole world.

The melody of this niggun is so deep and meaningful that it is only sung at very special occasions, such as weddings. It captures the general essence of our purpose as the Jewish people and also our specific purpose as individual souls. It reminds us what our purpose is, and also that to fully understand Hashem’s wisdom, we need music.

Singer Shlomo Gaisin and guitarist Zacharia Goldschmiedt make up the Hasidic folk band Zusha. Their most recent album is Cave of Healing.

Reading Shalom Aleichem

EVGENY KISSIN

Russian • 20th century • Lyrics and music by Rafail Khozak

IN 1986 IN THE Soviet Union, when I was about 14 and a half and at a music retreat, I met a Russian composer by the name of Rafail Khozak. I had not heard of him before. A few days after I met him, he said he wanted to show me something. He sat down at a piano and began to play soft and melancholy music. He confirmed, after the first few bars, that it was, to my surprise, Jewish music. Composed for violin and piano, it was a piece from the suite he had written, entitled “Reading Shalom Aleichem.” At first the piece, which was called “I shall tell you, sonny…,” was melancholy, but in the middle it became more dramatic. The second piece, “Hopes, Hopes…,” was much livelier, and the third, “And again we are together,” which was in a minor key, was energetic and joyful.

After that we started spending time together. He introduced me to Jewish music and to many other things. He taught me about Jewish history and culture, about the State of Israel and that the Soviet Union was the most anti-Semitic state. Up until then, my only knowledge was through Soviet propaganda. I had grown up an assimilated Jew in a nonobservant, nonpolitical home.“I want you to get to know yourself,” he said. He told me not to be ashamed of my Jewishness.

The interaction with Khozak, who was originally from Latvia, opened my eyes and I was grateful for that. He died three years later at age 59. I want his name and music to be known worldwide. Recently, I managed through one of his relatives to get a copy of the score of his Jewish suite. Unfortunately, I haven’t had an opportunity to play the music in concert yet, but I very much hope that I’ll be able to do so in the not very distant future. That would give me great pleasure and satisfaction.

Evgeny Kissin is a pianist and composer known for his interpretations of Chopin, Schumann, Liszt, Brahms and Rachmaninoff, who also performs Yiddish poetry.

Highway 61 Revisited

JOE LEVY

English • 1965 • Lyrics and music by Bob Dylan

THERE ARE MANY great songs about the Jewish experience in America, but they are about America itself, and rather than enact assimilation, they reshape the America they are describing. They are by Irving Berlin or Sammy Cahn or Leiber and Stoller. The one I’m listening to now is by Bob Dylan. It is called “Highway 61 Revisited.” “God said to Abraham, ‘Kill me a son,’” it begins. “Abe said, ‘Man, you must be putting me on.’”

To appreciate this song, you do not have to know that Bob Dylan’s father was named Abram Zimmerman, or that Dylan grew up Jewish in Hibbing, Minnesota, 75 miles north of Duluth, where Highway 61 begins its run straight down to New Orleans. You do not need to know the song “61 Highway” as recorded in 1964 by Mississippi Fred McDowell, or even the story of the binding of Isaac, as told in Genesis 22. Maybe it helps to remember that America was a mess when this song was written, as it is now. But really the song requires nothing more than open ears. It is a comedy with menace, a vaudeville routine about the end of everything. It smiles. It cries. And it never stops moving, changing the landscape as it goes.

Joe Levy is a former editor of Rolling Stone and currently editor-at-large for Billboard. He also hosts the podcast “Inside the Studio.”

Lithuania

EZRA FURMAN

English • 2002 • Lyrics and music by Dan Bern

DAN BERN IS A perennially underappreciated folk singer from Iowa whose records taught me to write songs when I was a teenager. “Lithuania” is probably his longest song, exceeding 11 minutes in the studio version released on his 2002 Swastika EP. The first half of it is the part that really gets me. That half is less song than memoir, or a kind of cultural manifesto monologued over two alternating chords. For five melody-less minutes, Bern tells us why he has “one foot in the black-and-white two-dimensional ghosts of Lithuania and the other foot in sunny California where the people are all friendly as they drive their Mercedes to the mini-malls and take a lunch or network with you or drive past and kill you for no reason.” His father’s extended family was killed in the Holocaust; somehow his father escaped to the United States and had children.

The song as a whole is a confession of Bern’s failure “to be a good American and write an elegy to the automobile.” One senses a touch of resentment of all-American imagery like that offered by Bruce Springsteen, one of Bern’s heroes. But where rock’n’rollers with American ancestors feel belonging and a sense of unconscious familiarity, the child of European refugees feels alienation and no small amount of envy. He feels utterly dislocated in California, where materialism means freedom and freedom has no limit. He is only barely historically removed from mass slaughter at the hands of the powerful, and psychically it’s at the center of his life. Though he sometimes tries to push those ghosts away and lean into the American dream, it never quite takes.

I’m the grandchild of Holocaust refugees. This song gets at a haunted, displaced feeling that I’ve known my whole life and that I think is familiar to many Jews descended from survivors. But it’s the triumph and resolve that move me most, when Bern imagines dancing on Hitler’s grave and shouting the names of Jews who made it in America: “Groucho Marx, Lenny Bruce, Leonard Cohen, Philip Roth,” and on and on. He marvels at his father’s ability to have a sense of humor after his family was all shot by Nazis, and it hits him: “I must go on…It would be an aberration to do anything else.” And at last, he’s able to start singing.

Ezra Furman, a singer-songwriter, has released eight albums, most recently Twelve Nudes. In 2019 Furman scored the soundtrack to the Netflix comedy Sex Education.

Rhapsody in Blue

HOWARD REICH

English • 1924 • Composed by George Gershwin

THE WORLD MAY NOT think of George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” as a piece of Jewish music, but to me it embodies the Jewish experience in America—at least in the early 20th century. Yiddish melodic inflections coursed through the art of its composer, a son of Russian Jewish immigrants born Jacob Gershwine in Brooklyn. The piece’s opening clarinet wail, an ascending glissando of a sort never heard before in American music, simultaneously fused Old World klezmer music with “le jazz hot.” From the composition’s first notes, Gershwin was proclaiming that a new sound and a New World were upon us, a thrilling—if unexpected—merger of Yiddish culture, European classical music and African-American jazz (not necessarily in that order). After that still-stunning clarinet solo, the piece surges forward with unstoppable, ferociously syncopated rhythm, the lifeblood of jazz. In no time at all, Tchaikovsky-like phrases, blue-note melody-making, whinnying jazz-band horns and Lisztian piano virtuosity are tumbling one upon the other. These far-flung musical cultures are freely mixing and merging, just as the Jewish immigrants and others like them did as they passed through Ellis Island. Were it not for America’s open arms at that time, Jewish culture would not have gone on to shape Broadway and Hollywood, and “Rhapsody in Blue” would not exist.

No piece of music more dramatically crystallizes what Jews brought to American culture than “Rhapsody,” with its oft-frenetic pace, passages of deep nostalgia and longing, and then-groundbreaking celebration of Black music. When Gershwin and Paul Whiteman and his orchestra played “Rhapsody” at its world premiere on February 12, 1924, in New York’s Aeolian Hall, they weren’t just bringing jazz to the highbrows; they were spotlighting Jewish and Black art as central to the American experience.

Howard Reich has been a music critic at the Chicago Tribune since 1978. He has written six books and written and co-produced three documentary films.

It Ain’t Necessarily So

TOVAH FELDSHUH

English • 1935 • Lyrics by Ira Gershwin; music by George Gershwin

GEORGE AND IRA Gershwin, the children of Russian immigrants, immediately come to mind as a composer and lyricist who took Jewish melodies and transformed them into some of the great classics of the American songbook.

For instance, most extraordinarily, take the blessings that one says on the bimah before reading from the Torah. The words are “Bar’chu et Adonai ham’vorach, Baruch Adonai ham’vo-rach l’o-lam va-ed” (“Let us praise the one to whom our praise is due, praised be the one to whom our praise is due now and forever”). In his opera Porgy and Bess, George Gershwin echoes those Torah blessings in the song “It Ain’t Necessarily So.” The lyrics go: “So the things that you’re liable to read in the Bible/ It ain’t necessarily so.” But the melody and phrasing of the music are almost identical to the blessings, as is the rhythmic repetition.

George probably heard those melodies as a little boy going to synagogue with his parents. He certainly heard them when his brother, Ira, was bar mitzvahed, as he flanked his brother at the bimah with his father, Maurice. There were many other melodies that George extracted from childhood. One of them was a Russian Yiddish lullaby by Abraham Goldfaden called “Schlof in Freydn” (“Sleep in Joy”). George referenced it as the inspiration for his song “My One and Only,” from the musical Funny Face. You can hear it under the words, “My one and only/What am I gonna do if you turn me down/When I’m so crazy over you?”

The Gershwins not only took Jewish music and spread it out into American culture, they also took Jewish music and made it personify metropolitan culture. There is nothing more bustling and more emblematic of the great city of New York than George’s “Rhapsody in Blue.”

Tovah Feldshuh is an American actress, playwright and singer. She has been a Broadway star for more than four decades and has also appeared on television and in films, earning four Tony and two Emmy Award nominations.

Fanfare for the

Common Man

ARI SHAPIRO

1942 • Composed by Aaron Copland

AARON COPLAND’S “Fanfare for the Common Man” feels like one of the most quintessentially American pieces of music ever written. It was written for the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra under conductor Eugene Goossens in response to the U.S. entry into World War II. It was inspired in part by a speech made earlier that year by then-U.S. Vice President Henry A. Wallace, in which Wallace proclaimed the dawning of the “Century of the Common Man.”

The chords are open, expansive and optimistic. And the fact that it was written by a gay Jewish son of immigrants strikes me as essential. In Copland’s music, the Jewish experience isn’t a thing apart from American identity but is indistinguishable from it. His “Fanfare” is both heroic and universal. It is a promise that anyone can achieve greatness, no matter their history or origins.

Ari Shapiro is the cohost of NPR’s “All Things Considered” and a frequent guest singer with the band Pink Martini.

If I Were a Rich Man

MICHAEL STEIN

English • 1964 • Lyrics by Sheldon Harnick; music by Jerry Bock

FIDDLER ON THE ROOF tells the story of Jews living in the Pale of Settlement in the early 1900s, a world lost to pogroms and persecution. Inspired by Shalom Aleichem’s character Tevye the Dairyman, the musical uses the modes that make Jewish music sound like Jewish music—the mode called phragish or Ahava Rabba, the mixture of minor and major keys that became part of not just the Jewish musical lexicon, but also the American musical vocabulary. Most Americans can hum songs from the show, and most do not realize that they are singing in the style of our great Hasidic masters and their communities. That is why this stage play had such a powerful impact on the Jewish experience and culture. Songs about Shabbat, about prayer, about the secular-religious struggle paint a picture of life in the shtetl for everyone to see and contemplate. Jerry Bock, Sheldon Harnick and Joseph Stein (who wrote the book for the musical) didn’t think Americans would be that interested, but Fiddler became one of the longest-running shows on Broadway and remains as popular and beloved today.

There is one song in particular that I would like to point to. “If I Were a Rich Man” teaches us that riches, to the Jewish soul, are not possessions but rather our rich heritage, filled with love of Torah and our fellow beings. Tevye was poor, but how did he describe being wealthy? Having the time to be the Rebbe who would teach his flock, having a seat by the Eastern Wall, having time to study and to pray—these Jewish values that have “no prescribed measure” as we pray each morning (Mishnah, Peah 1:1).

My friend, the late Theodore Bikel, performed the role of Tevye and sang this song more than anyone else. When I talked with Sheldon Harnick recently, he said that Theo was “the best Tevye that there ever was, because he lived the part.” Harnick went on to say that Theo did not play the role for comedy, but with a seriousness that yearned for days gone by and with hope for a better future.

When I first saw Fiddler on Broadway, I remember my mom sat there and cried from the first note of the overture. As a child, I was embarrassed that she cried, but when I saw Theo play Tevye in Los Angeles about 18 years ago, I too cried, because I was reminded of the richness of our history.

Why do the Jewish people continue to exist? Some would say it’s because of the Passover seder—a night where we gather, tell our story and sing. Fiddler on the Roof is America’s Passover seder. It captures our story, our spirit and our culture because it is genuine, and based on our story of our people, Am Yisrael.

Michael Stein has been the hazzan at Temple Aliyah in Los Angeles for almost 20 years, and began his career as a member of the original cast of Jesus Christ Superstar on Broadway.

Avodat Shabbat

LOWELL MILKEN

Hebrew & English • 1958 • Text from the Reform Friday evening Shabbat service;

music by Herman Berlinski

AFTER RECORDING more than 600 works, choosing one favorite is a tall order! The work I have done in preserving Jewish music has brought me into contact with so many remarkable artists and compositions. Yet Herman Berlinski’s “Avodat Shabbat” left a deep and profound impression.

I got to know Berlinski in April 2000, while recording this masterpiece with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra. Berlinski was an individual of intense spirituality and vitality. He had an infectious personality and a fantastic sense of humor. But “Avodat Shabbat,” an elaborate Sabbath eve service, will remain forever close to my heart for three reasons.

First, it validated the Milken Archive’s work to preserve and disseminate music of American Jewish experience. People have many opportunities to hear sacred services by well-known composers like Ernest Bloch and Darius Milhaud. Yet there are equally great sacred works that few know or will ever get the opportunity to hear. Indeed, the Berlin recording was the composer’s first opportunity to hear it performed with a full orchestra, soloists and a chorus of the highest caliber.

Second, the experience we had recording this work in the country that Berlinski once fled highlighted music’s ability to heal, to transcend differences. To be part of the process that brought Berlinski back to Germany for the first time since 1933; to watch his face as he listened to a 100-voice German chorus, not one of whom was Jewish or had sung in Hebrew previously; to be seated next to the composer as he listened to his magnum opus being played as he had conceived it describes one of the most moving experiences of my life. The composer at my side felt it, too.

Finally, “Avodat Shabbat” is the most important piece of Jewish music for me because it moves me in a way that few other works can. Its majesty and grandeur, its emotional peaks and valleys, its melodic freshness and harmonic complexity personify what all great music should be, Jewish or otherwise.

Four months after the time we shared in Berlin, I received a handwritten letter from Berlinski: “A score is nothing but paper. It is silent and unlike painting, does not reveal itself by just looking at it. A recording however…brings the work to the attention of those who eventually may want to perform it, or at least will form an opinion about it. This, to a living composer, means the possibility of survival.”

Sadly, Herman Berlinski died not long after writing those words. His life was a triumph of survival and talent. How grateful I am for the opportunity to have played a part in ensuring that his music lives on.

Lowell Milken is the founder of the Milken Archive of Jewish Music, which collects, records, preserves and documents Jewish musical history for current and future generations.

Baby Moshe Taken

from the Water

BARBARA C. JOHNSON

Malayalam • 1876 • Lyrics and composer unknown

“BABY MOSHE Taken from the Water” is a song from a collection of more than 300 folk songs in the Malayalam language of Kerala, on the southwest coast of India, traditionally sung by women from the Jewish community there. Their ancestors lived a safe and prosperous life there for at least a thousand years before their 20th-century migration to Israel, where they are popularly called “Kochinim” because most lived in the former Kerala kingdom of Cochin (Kochi).

Kochini women sang their Jewish folk songs at home and in community gatherings, where the men listened respectfully. Women knew the Hebrew liturgy and piyyutim [liturgical poems] too and sang along with the men at the table and from their separate section in the synagogue. To preserve their Malayalam folk songs, the women singers wrote them down in notebooks, which were passed on from one generation to the next.

I chose the song “Baby Moshe Taken from the Water” in particular because it has such a Kerala cultural flavor. The coastal backwaters of Kerala flow to the sea from small streams through bigger rivers to lagoons surrounded by villages, and as you listen to the Bible story of how the baby Moses was saved by his mother, if you’ve been in Kerala, you can just see it all happening. You can imagine this box being gently lowered into one of the streams, then floating into a bigger river and landing by a grand house—the palace of Pharaoh, whose daughter rescues baby Moshe.

The song is also a tribute to Kochini women’s Jewish education. Like many of their songs it refers to Midrash as well as the Bible, in this case the legend that the daughter of Pharaoh made Moses strong by caressing and nourishing him. The melody is very gentle, sort of a rocking melody that could be sung as a lullaby. It is a song about women, sung by women and passed down to women—Jewish women who sang to their children like women everywhere, and who also were educated and respected for their knowledge.

Barbara C. Johnson is emerita professor of anthropology and Jewish studies at Ithaca College in New York. She is the coauthor of Ruby of Cochin: An Indian Jewish Woman Remembers with the late Kochini song expert Ruby Daniel, and editor of the audio collection Oh, Lovely Parrot: Jewish Women’s Songs from Kerala.

Recording: Performed by Simcha Yosef and Hannah Yitzhak, from the CD Oh, Lovely Parrot!: Jewish Women’s Songs from Kerala

Click here to read an extended answer from Johnson.

Rozo D’Shabbos

JEREMIAH LOCKWOOD

Aramaic • 1928 • Text adapted from the Zoohar; recorded by Cantor Pierre Pinchik

“ROZO D’SHABBOS” (“The Secret of Shabbos”), originally recorded by Cantor Pierre Pinchik in 1928, is for me one of the touchstones of what Jewish music can achieve. I’m not alone in this opinion; “Rozo D’Shabbos” is still one of the most popular pieces of the cantorial canon. Pinchik was born to a Hasidic family and started his musical life as a choirboy in elite choral synagogues in Ukraine. A classically trained tenor and pianist with modernist leanings, he was a star of the early Soviet folk music circuit. After immigrating to the United States, he reinvented himself as the greatest cantor in the Eastern European style.

Pinchik’s recording takes as its subject a text from the Zohar found in the Hasidic liturgy, not the “standard” Ashkenazi prayer book. His setting of “Rozo D’Shabbos” is one part auto-ethnography of Hasidic prayer, two parts theatrical restaging of memory as a site of mystical experience, and three parts outrageous hyper-emotional outpouring that lifts you into an experience of prayer. It was well known that Pinchik was not strictly observant, and it was whispered that he was gay—items in his profile that were a matter of interest but that did not keep him from being invited to officiate from the most prestigious synagogue pulpits of his day. My grandfather told me that his grandfather, a misnagdishe rabbi, said of Pinchik, “That damned apikoros (non-believer) made me cry.”

Jeremiah Lockwood is a singer, instrumentalist and composer known for his work with traditional Jewish music and blues. He is the front man of the band The Sway Machinery.

Cantata of the

Bitter Herbs

GERARD SCHWARZ

English & Hebrew • 1938 • Lyrics by Jacob Sonderling and Don Alden; music by Ernst Toch

IF I HAD TO PICK pick one piece that has a deep significance for me, it’s Ernst Toch’s “Cantata of the Bitter Herbs.” I fell in love with this piece from the moment in 2000 when I started studying it, while conducting it in Prague for the Milken Archive with the Czech Philharmonic and the Prague Philharmonic Choir.

Toch, who would go on to win a Pulitzer Prize, was born in Austria. He came to New York to teach in 1934, then went to California and wrote film scores, symphonies, operas, chamber music, choral music and vocal music. He was Jewish, but he wasn’t a regularly practicing Jew. When his mother died in Austria in 1937, he couldn’t go back for the funeral, and he was very upset. He decided to try to find some kind of peace by going to the Fairfax Temple in Los Angeles. There, the very well-known and highly educated rabbi, Jacob Sonderling, befriended him. Toch became part of that congregation and ended up writing this cantata, with lyrics by the rabbi. It’s not an opera but a dramatic vocal work based on the story of the Jews’ exodus from Egypt and the Haggadah. In our 2000 recording, it was poignantly narrated by Theodore Bikel.

Interestingly, the cantata has never really entered the standard repertoire as it should have. It’s only about half an hour long, while most of the great Old Testament oratorios by Mendelssohn and Handel are a whole evening’s work. If you’re going to assemble four soloists, a chorus, a narrator and an orchestra, it has to go with other works. As a result, it’s been very rarely played.

Gerard Schwarz was the music director of the Seattle Symphony for 26 years. Currently the music director for the All-Star Orchestra and the Eastern Music Festival, he has received numerous honors, including Emmys and Grammy nominations.

Eshet Chayil

PERL WOLFE

Hebrew • 1953 • Lyrics from Proverbs 31: 10-31; music by Ben Zion Shenker

I HAVE ALWAYS loved “Eshet Chayil” (“Woman of Valor”), which is sung before the Friday night Kiddush in Jewish homes, perhaps since the 17th century. I love both the classic tune and the words. Specifically what I love is that it’s about this bad-ass woman. She’s an entrepreneur building her empire; she is humble and kind. Some might view the song as old-fashioned and think that it sets expectations to be a perfect woman. But the last line of the 22 verses is “Sheker hachen v’hevel hayofi ishah yir’at Adonai hi tit’halal/T’nu lah mip’ri yadeiha vihal’luha vash’arim ma’aseha” (“Charm is deceptive, and beauty is naught, a woman who fears God, she shall be praised/Give her praise for her accomplishments and let her deeds laud her at the gates”). Her work speaks for itself. The focus is on her accomplishments, not on her looks, and I have always found that empowering.

Perl Wolfe is a singer, songwriter and musician. She cofounded and was the lead singer of Bulletproof Stockings, an all-women Hasidic rock band. She released her debut solo album, Late Bloomer, this year.

Women of Valor

NOREEN GREEN

English, Hebrew & Yiddish • 2000 • Lyrics drawn from the Bible and modern poetry and prose; music by Andrea Clearfield

AS A CONDUCTOR of a symphony, I’m always looking for new music of the Jewish experience. “Women of Valor” presents music of the women of the Bible, composed by a woman, conducted by a woman, sung and narrated by women. It’s all about the women’s perspective in the Bible. Clearfield came up with ten arias that highlight the stories of ten biblical women: Sarah, Leah, Rachel, Yocheved, Miriam, Hannah, Yael, Michal, Ruth and Esther. For instance, in the story of Leah and Rachel, Rachel fell in love with Jacob, and Laban tricked Jacob into working seven more years because he gave Jacob his older daughter Leah first. Can you imagine that wedding night? What was it like for Leah, knowing that Jacob thought she was Rachel? And what was Rachel thinking, giving her beloved up because her father wanted to marry off the older daughter first? We don’t get the women’s perspectives in the Bible.

The text and the lyrics are by contemporary female lyricists or poets or writers such as Alicia Ostriker, Marge Piercy and the Israeli poet known as Rachel, and drawn from the Bible, including portions from Genesis, Judges and the Book of Esther as well as the entire “Eshet Chayil” (“Woman of Valor”) poem from Proverbs, traditionally read on Friday nights in Jewish homes. The work is called “Women of Valor,” because that text is the glue that holds the spoken dialogues together. Very much as in an opera, you have recitatives and arias. The musical material for “Women of Valor” incorporates ancient Hebrew synagogue chants as well as other traditional melodies.

For me as a female conductor and Jewish woman, this piece—and the music is just gorgeous—exemplifies a different aspect of Judaism. Clearfield starts the piece with Sarah, the mother of Judaism. And the last woman is Esther, who saves the people. As a result, “Women of Valor” concludes with the idea that a woman saves the Jewish people.

Noreen Green is the artistic director and conductor of the Los Angeles Jewish Symphony, which she founded in 1994, and the newly formed Jewish Community Chorale.

NURIT BAR-JOSEF

WHAT COMES TO mind is the connection I always feel when playing a Gustav Mahler symphony. It is partly because Mahler was Jewish. He converted to Catholicism in the late 1800s, apparently to further his conducting career in Austria and Germany.

I love all of his symphonies, but my favorite is “Symphony No. 1.” In the slow third movement, you can hear, very well, coming out of nowhere, a faraway sound of klezmer music in Bars 39-60 (according to one commentator, “redolent of Bohemian village bands from Mahler’s youth”). What makes it sound like a klezmer band is the way Mahler uses the trumpet duet and clarinet melodies, with the strings playing “col legno” (a percussive technique where we flip the bows and hit the strings with the wooden part of the bow), and the cymbals keeping the beat. Then it goes away, and we return to a big Mahler symphony.

Mahler was not religious. He did convert to Catholicism and married a non-Jew. But the fact that he brought these klezmer melodies and little bursts of his background into his music tells me that there was perhaps always a struggle there. He died young, at age 50. I wonder what else he would have composed and how far he would have dug into his Jewish ancestry. What other melodies would he have thrown into his music that were Jewish?

There are also Jewish songs that I am drawn to. One of the most beautiful is “Jerusalem of Gold,” “Yerushalayim Shel Zahav” in Hebrew. It was commissioned by the mayor of Jerusalem and written for the Israeli Festival held on May 15th, 1967, the night after Israel’s 19th Independence Day. It was initially offered to be the Israeli national anthem. As a kid in the 1970s, I spent many summers in Jerusalem and I heard that song a lot and it brought tears to my eyes. It reminds me of what my people went through, including my grandparents, who arrived with nothing, taken away from their own families at such a young age, having to raise children and make things work for themselves—the suffering that they had to go through. And it is just a beautiful song, whether you are Jewish or not.

Violinist Nurit Bar-Josef has been concertmaster of the National Symphony Orchestra since 2001.

YEFIM BRONFMAN

Symphony No. 1 in D Major

1887-1888 • Composed by Gustav Mahler

THERE ARE NUMEROUS Jewish themes running through the music of Russian composer and pianist Dmitri Shostakovich. His string quartets come to mind, and his piano trio has a fantastic Jewish theme. He lived through World War II, the Holocaust and the murder of the Jews in Russia, which nobody talks about. He wasn’t Jewish but his wife was. He knew exactly what was happening and captured it very well, for example, in his 1962 “Symphony No. 13 in B Flat Minor (Op 113),” subtitled “Babi Yar.” His symphony was inspired by a 1961 poem by Yevgeny Yevtushenko that protested the Soviet Union’s refusal to recognize Babi Yar—the ravine on the outskirts of Kyiv where Jews were massacred in 1941—as a Holocaust site.

While Shostakovich reflected on the Holocaust, Ernest Bloch, a Swiss-American Jew, reflected the Jewish religious sensibility. I would say that Bloch’s “Schelomo: Rhapsodie Hébraïque for Violoncello and Orchestra” has great significance for Jews. It was part of his Jewish cycle and is based on the Bible and Jewish religious themes. Shlomo or Schelomo is the Hebrew form of Solomon, and Bloch uses the violoncello to represent the voice of King Solomon. Then there is Gustav Mahler, the Austro-Bohemian Romantic composer and opera conductor. Although he converted to Christianity, Jewish folklore runs in and out of his symphonies, for example, in the klezmer-like melodies in his Symphony No.1. Musically, Mahler was very much influenced by the German opera composer Richard Wagner. But maybe there also is some Jewishness. He converted, but you cannot change your heart. The Jewishness comes through in the string sounds and some other sounds that we associate with Jewish music. In retrospect I think that klezmer music comes from Mahler’s music rather than vice versa. I don’t think that Mahler could have predicted that.

Yefim Bronfman is one of the world’s foremost concert pianists. Born in the Soviet Union, he immigrated to Israel at age 15 and became an American citizen in 1989.

Hatikvah

EDWIN SEROUSSI

Hebrew • 1877/1888 • Lyrics from Naftali Herz Imber’s 1886 poem “Tikvateynu;” music adapted by Samuel Cohen from “Carul cu Boi” in 1888

“HATIKVAH” TODAY is revered as an anthem, but at its roots it is a folk song, made by the people, sung by the people. We don’t usually know the provenance of folk songs’s words or music, but in the case of “Hatikvah” we do. When the poet Naftali Herz Imber came to Ottoman Palestine, he toured around the Jewish settlements and recited his poems in public. His poems became beloved, and he eventually published a collection of them in Jerusalem in 1886. One was called “Tikvateynu” (“Our Hope”). People tended to attach well-known melodies to poems so they could sing them, and many people suggested melodies for “Tikvateynu.” One new immigrant from what is now Moldova, Samuel Cohen, set the poem to the melody of “Carul cu Boi” (“The Ox-Driven Cart”), a nostalgic Moldavian song, itself one of many versions of a melody floating around Europe at the time.

The melody is almost identical to the melody of “Hatikvah.” What is important, however, is that the “Hatikvah” melody has two parts, an A part and a B part. There’s a big jump, an octave, at the beginning of the B part, which is unique to “Hatikvah.” That jump says that we still have not lost our hope. It’s like a cry. It’s a shout. It’s repeated, and then you go back down and you are back where you started. The Romanian folk song also goes up in the second part, but it doesn’t go up so dramatically or by an octave. Both songs end the same way.

Why this melody succeeded over other melodies put to “Tikvateynu,” nobody knows. But it’s obvious that one reason is its simplicity. It’s easy to learn, it has this Jewish sadness, but it also has the jump of the octave, which is assertive and hopeful and forward-looking.

The song leaped over the sea and spread like wildfire around the world, becoming the anthem of the Zionist movement in 1933, and eventually, Israel’s anthem. (It only became the official national anthem in 2004!) Usually anthems are commissioned or selected by some authority. “Hatikvah” is one of the few anthems that came from the bottom up.

Edwin Seroussi is a professor of musicology and director of the Jewish Music Research Centre at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. He was awarded the Israel Prize in 2018.

Click here to read an extended answer from Seroussi.

Hava Nagila

Hebrew • 1918 • Lyrics and music by Moshe Nathanson and Abraham Idelsohn

NISSIM BLACK

“HAVA NAGILA” (“Come, Let Us Rejoice”) is probably the most classic Jewish song. It’s about simcha, joy, and Judaism should be about simcha. That joy is in the lyrics, but the niggun—melody—itself is so upbeat and happy. It’s such a classic that I definitely heard it before I was Jewish. When I started listening to Jewish music, some of the first things I came across were medleys of songs without words, and “Hava Nagila” was one of them. I used to listen to it all the time.

In Judaism, all of our holidays are times for simcha. Shabbat is a time to have oneg, enjoyment, and even throughout the week there is always some sort of special occasion—a wedding, a bris, a bar mitzvah. There are so many things in Judaism that call for people to be joyful, and that’s especially meaningful for me as a Breslover Hasid. Rav Nachman says that the main mitzvah is lehiot b’simcha tamid—to always be joyful. This experience of Judaism has influenced my music. Music is a keli, a vessel, so whatever is inside of you pours out into your music. I live a Jewish life, so naturally, that’s what comes out in my music.

Nissim Black, born Damian Jamohl Black, is an African-American Hasidic Jew who converted in 2012. His latest rap single, “RERUN,” was released earlier this year.

ROBERTA GROSSMAN

“HAVA NAGILA” is hands down the most important song in the Jewish canon—maybe not the most loved song, maybe even the most derided song, but still the most important song. If you meet any Jew (and most non-Jews!) and start singing the first couple of bars, they will know exactly what song you are singing. It’s the most ubiquitous piece of Jewish cultural identity, with maybe the exception of the bagel. “Hava Nagila” is a little snowball that becomes a giant glacier as it rolls across continents and decades, picking up the entire Jewish experience of the 19th and 20th centuries as it goes, from Ukraine to YouTube. Its origins are a wordless Hasidic niggun in Ukraine, from where it then traveled to Palestine, where lyrics were added to the tune by Abraham Idelsohn. It became a beloved Israeli folk song and eventually found its way to America, becoming the quintessential expression of American Judaism in the 1950s and 1960s, only to become universally hated in the 1980s and 1990s. Part of its impact is the catchy tune that is both joyful and melancholy coupled with the simple lyrics (“Come! Let us rejoice and be happy!”) Ultimately the song’s lasting resonance is perhaps due to its being associated with the happiness of weddings, bar mitzvahs and other joyous milestones.

Roberta Grossman is a film producer, director and writer, with a focus on social justice and Jewish history. Her feature-length documentary Hava Nagila: The Movie was released in 2012.

YAAKOV SHWEKEY

Jerusalem of Gold

Hebrew • 1967 • Lyrics and music by Naomi Shemer

AS A SINGER for 20 years, touring around the world and going to so many different communities, you realize that some songs break the barrier of speech and language and whatever differences there are in culture. Music is something that goes into the heart, into the soul, of every Jew. I think the greatest language we have today is the language of music. And that’s the language of the soul.

My father’s family was Egyptian and Syrian, but my mother was Ashkenazi. She was born in a displaced persons camp. Her mother had survived Auschwitz. She was a very, very humble, righteous woman. She was always proudly saying that she was Jewish. She never wanted to hide the fact. I wrote a song titled “We Are a Miracle” because it relates our history as a Jewish people, and because the greatest miracle in the world is the fact that the nation of Israel is still around, after all we’ve been through—so many pogroms and so many Inquisitions and the Holocaust. I think music is probably one of the greatest ways to teach our youth history. They have to see, they have to feel, and they also have to hear.

So “We Are a Miracle” is something that we should sing with pride. We have a great tradition that goes back thousands of years.

I also want to mention “Jerusalem of Gold” (“Yerushalayim Shel Zahav”). I sang that song in 2017 at a Jerusalem Day assembly of some 100,000 people at the Western Wall commemorating 50 years since the liberation of the Wall. It’s probably one of the most famous Israeli songs. I decided to sing it because it is a song that is very well known among so many different types of people. It’s a very poetic song, and I wanted the audience to feel what the city is all about. We were there to celebrate the fact that we have Jerusalem, we have the Western Wall, and we’re able to go there and pray. It’s a miracle that we’re able to go there and connect.

Yaakov Shwekey is an Orthodox Jewish recording artist and entertainer. He was born in Israel and immigrated with his family to the United States.

Click here to read an extended answer from Shwekey.

Kol Nidre

KENNY VANCE

Aramaic • Date Unknown • Traditional Yom Kippur liturgy

IN THE 1950s, I was into doo wop music. It vibrated inside of you. It wasn’t an intellectual thing, it was something your parents told you not to do. My father would take me to shul in Brooklyn on the High Holy Days. I wasn’t very interested in Judaism then but I remember, the night before Yom Kippur, hearing this incredible guy wearing these majestic robes and maybe some sort of ornate metal thing around him sing “Kol Nidre.” It was awe inspiring. It was reverential. There was a certain type of trepidation attached to it. It was the first piece of Jewish music that I had an inner connection with. Even then, “Kol Nidre” was more to me than just a song.

Kenny Vance was an original member of Jay and the Americans and sang with the group on all their hits, including “Only in America” and “Come a Little Bit Closer.” He still sings with his own group, The Planotones.

Click here to read an extended answer from Vance.

DAVID BROZA

THE MOST SIGNIFICANT piece of music coming from my Jewish heritage is “Kol Nidre,” which is deeply connected to the culture of Jewish life around the world. Literally meaning “all vows” in Aramaic, it is actually a declaration of vow annulment. The prayer itself is older than the haunting melody, which may have originated in Germany between the 11th and 15th centuries. Together, the words and music have been passed from one community, one country, one continent to the next, and “Kol Nidre” has become the central and most important moment in prayer on the eve of Yom Kippur.

Another piece from my heritage is the beautiful Israeli love song “Evening of Roses,” “Erev Shel Shoshanim” in Hebrew. My mother, Sharona Aron, was Israel’s first folk singer. She played the guitar, and there was always music at home. Her albums are found all over the world and were part of the emerging Israeli folk-song movement. I’ve always loved her recording of “Erev Shel Shoshanim,” which became a hit. The song was written by Israeli composer Yosef Hadar and the lyrics by poet Moshe Dor. The piece is often played at weddings when the bride enters the chuppah. Many synagogues use the melody to sing the piyyut [liturgical poem] “Lecha Dodi” (“Come, My Beloved”) during the Kabbalat Shabbat prayer service on Friday night.The melody is even used in Christian prayer as “Hymn No. 15” in the Lutheran Church in northern Europe.

Raised in Israel, Spain and England, singer-songwriter and guitarist David Broza blends a folk rock and rock-and-roll sound with modern pop and flamenco rhythms. His newest, and first all-instrumental album, En Casa Limon, was produced by Grammy-award-winner Javier Limon.

Olam Chesed Yibaneh

NESHAMA CARLEBACH

Hebrew & English • 2001 • Lyrics and music by Menachem Creditor

“OLAM CHESED YIBANEH” (“We Will Build a World of Love”) is a song written by my husband Rabbi Menachem Creditor—but was meaningful to me way before I married him. “Olam Chesed Yibaneh” has become an anthem for these contentious times. It’s been sung all over the world—at rallies, in the Senate, even Bernie Sanders has sung and tweeted it. It’s everywhere; it has become like “Am Yisrael Chai” (“The Nation of Israel Lives”) for this generation. The words “I will build this world from love, you must build this world from love” are such a simple message; not only does hatred have no place here, but our world is ready to be transformed. The thing that moves me most about it is that people are now ready to hear it. The melody is super-simple, but hypnotic. It has a Jewish sound—once you hear it you know it. It’s gorgeous and simple all at once. It has the capacity to bring light and hope. There is so much about which we feel helpless, but if you can harness your own power to build from love it can really bring goodness to the world. We are living in a difficult world, and if we don’t speak our truth it crumbles around us. The first time I performed “Olam Chesed Yibaneh” was at the gate of Auschwitz during the March of the Living. Who better than survivors to tell us to bring a better world and look at brokenness and say we are blessed enough to bring a better tomorrow?

Neshama Carlebach is an award-winning singer, songwriter and educator who has performed and taught in cities around the world. Since her debut album, Soul, in 1996, she has released ten records.

Rozhinkes Mit Mandlen

ZALMEN MLOTEK

Yiddish • 1880 • Lyrics and music by Abraham Goldfaden

THE SONG “Rozhinkes mit Mandlen”(“Raisins and Almonds”) was written in 1880 by Abraham Goldfaden, who was considered the father of the Yiddish theater. He was a lyricist and a composer with no formal musical training, but he had an amazing ear, and memory, and he wrote Yiddish songs at the time when the Haskalah (Enlightenment) movement was just beginning. This particular song was from an operetta called Shulamis. Sung by traveling Yiddish theater troupes, it became a popular folk song all over the Jewish Pale of Settlement. It was comforting, and parents would sing it to their children as a lullaby. Many people remember hearing parents or grandparents or great-grandparents sing it to them.

The melody is beautiful in itself. What makes it a hit is the catchy tune. But more than that, I think, is the idea that there’s hope. While a baby boy is being rocked to sleep, the lyrics explain, the little goat standing under his cradle goes to market and returns with raisins and almonds. It’s a loving lullaby to children in the same way as “Hush little baby don’t say a word, Mama’s gonna buy you a mockingbird.” Despite the poverty and hardships people faced in ghettos at the time, mothers were singing to children about the idea that life and its possibilities are unlimited.

Zalmen Mlotek is a conductor, pianist, musical arranger, accompanist, composer and the artistic director of the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene.

Di Zun Vet Aruntergeyn

DANIEL KAHN

Yiddish • 19th century • Lyrics by Moshe Leib Halpern; music by Leibu Levin

I BECAME A FATHER recently, and I was just walking around the neighborhood with my wife, with our baby strapped to my chest, and he was crying. I started singing different songs, and the one that ended up putting him to sleep was a Yiddish song called “Di Zun Vet Aruntergeyn” (“The Sun Will Be Setting”), which is a poem by Moshe Leib Halpern. It’s important that in Yiddish there’s no difference in the word for “song” and the word for “poem”; they’re both called a lid. It’s in some ways a lullaby and in some ways a meditation on death, mortality, impermanence. The words—which are very beautiful, very mysterious—mention the sun going down behind the mountain. It’s also a love song; it has the image of the golden pave, the golden peacock, which is a symbol of Yiddish poetry. I’m a big fan of dark, sad folk music and ballads, and it definitely resonates with my musical sensibility. I’ve heard it sung by many of the Yiddish singers who inspired me to become one: Adrienne Cooper, Theodore Bikel, Michael Alpert, Lorin Sklamberg, Sarah Gordon.

I had considered picking a song by Leonard Cohen, something like “The Story of Isaac” or “Hallelujah.” But somehow, in finding the Jewish soul of some of our more familiar American music, you’re finding the ghost of that amazing Yiddish song and poetry material from the modern era that floats in the background of so much of the music that I love. “Di Zun Vet Aruntergeyn” is an example of that. It has a kind of eternal quality.

Daniel Kahn, a Berlin-based musician, leads the band The Painted Bird, which describes itself as “a mixture of klezmer, radical Yiddish song, political cabaret and punk folk.”

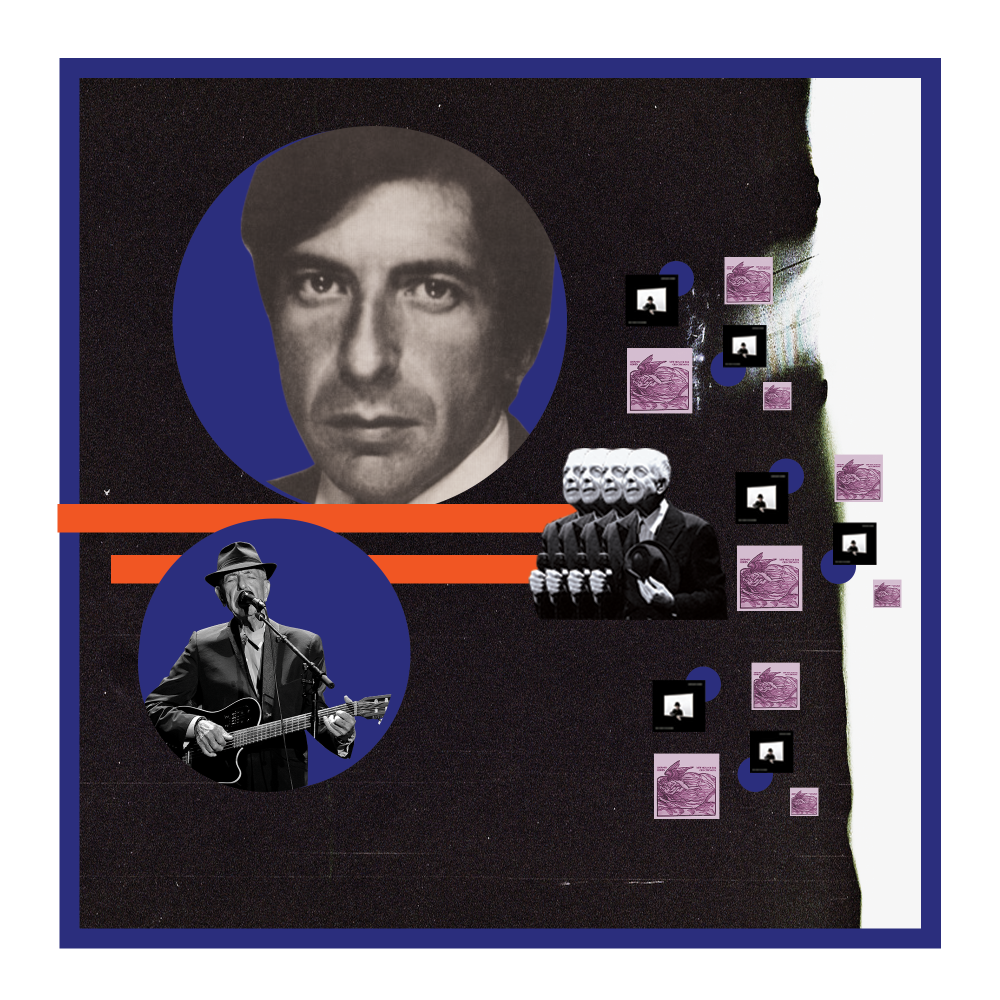

FRANCIS MUS

You Want it Darker

Hebrew & English • 2016 • Lyrics and music by Leonard Cohen

LEONARD COHEN often said that it was difficult for him to subscribe unambiguously to one religious tradition because he saw himself as a traveler, a stranger, who lived on the outskirts of many traditions. Yet his Jewish identity was often affirmed both in his work and life, and sometimes in a very ironic way. On his 1992 album The Future, he sings “I am the little Jew who wrote the Bible.” There is also a poem in his 2006 collection Book of Longing that is entitled “Not a Jew.” In the text itself, he says, “Anyone who thinks I am not a Jew is not right.”

“Who by Fire,” a track from 1974, is based on the Jewish prayer Unetaneh Tokef, which is chanted on Yom Kippur and asks who will live and who will die. The traditional version of the prayer raises issues that ultimately boil down to the fundamental question, “Who will be there in the end?” In Cohen’s version, he retains the form of the prayer as well as its melody. Each repetition ends with the question: “Who shall I say is calling?” Throughout his life, Cohen borrowed from religious and other traditions because ordinary language did not suffice to communicate the intensity of his experience.

For his 2016 album You Want it Darker, released several weeks before he passed away, Cohen literally returned to his hometown, Montreal, to collaborate with Gideon Zelermyer, the cantor of Congregation Shaar Hashomayim, the oldest and largest traditional Ashkenazi congregation in Canada, where back in the 1940s he had celebrated his bar mitzvah. On the title track, “You Want it Darker,” you can hear Zelermyer and the synagogue’s men’s choir performing in the background. There are several explicit religious references, starting with the repetition of the word hineni (“Here I am”). Cohen sings the Hebrew word Abraham uttered when God called upon him to sacrifice his son, then translates it as “I’m ready my Lord.” In the same song, he also sings, “A million candles for the help that never came.” When I first heard that line, I immediately thought of my own trip to the Yad Vashem’s Children’s Memorial in Jerusalem. Hollowed from an underground cavern, it pays tribute to the 1.5 million Jewish children who were murdered during the Holocaust. The memorial candles remembering them reflect infinitely in the dark and somber space, creating the impression of billions of stars shining in the firmament.

Francis Mus, a postdoctoral researcher in translation studies at the University of Antwerp, is the author of the book, The Demons of Leonard Cohen.

Click here to read an extended answer from Mus.

Avinu Malkeinu

FRANK LONDON

Hebrew • Date Unknown • Origins of the traditional prayer and melody unknown;

recorded by Alter Karniol, circa 1900