Mixed* Marriages

*How to survive when the state of your union divides along party lines

When the couple visits friends and family, liberal Democrat Amy Weiss has a simple admonition for her conservative Republican husband, Lou: “Just don’t be yourself.”

“I’ve been known to clear dinner parties,” Lou says, with sharp-edged conservative remarks that grate the ears of their mostly liberal Jewish social circles in Pittsburgh. To assuage his wife’s sensitivities, Lou printed up formal-looking cards that say: “Amy Weiss wishes to apologize for her husband’s behavior on the night of ——-.” Says Amy: “I make Lou hand them out on the spot, sometimes upon arrival at someone’s home before he has said anything.”

Lou and Amy Weiss

Are the cards a gag, or a practical way to head off trouble? “Both,” Amy says. In the lead-up to the 2016 presidential election, she half-jokingly threatened what she described as the Lysistrata treatment if Lou voted for Trump. “He’s a bad liar, so when he said he wrote my name in for president, I knew he was telling the truth,” she says. This year, Lou maintains his vote is up for grabs. “If the Democrats nominate Bernie,” he says, “I’m voting for Trump.”

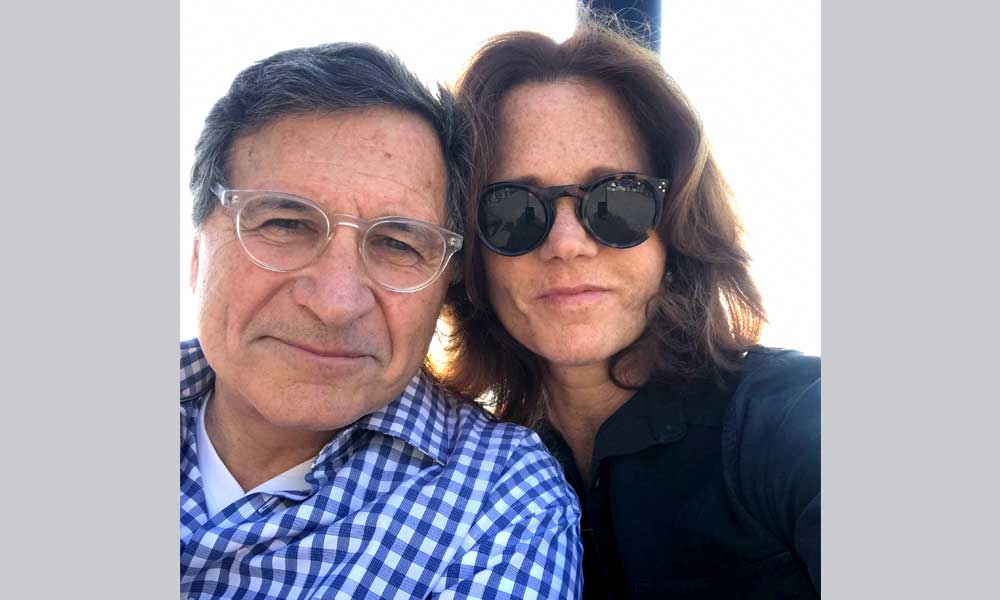

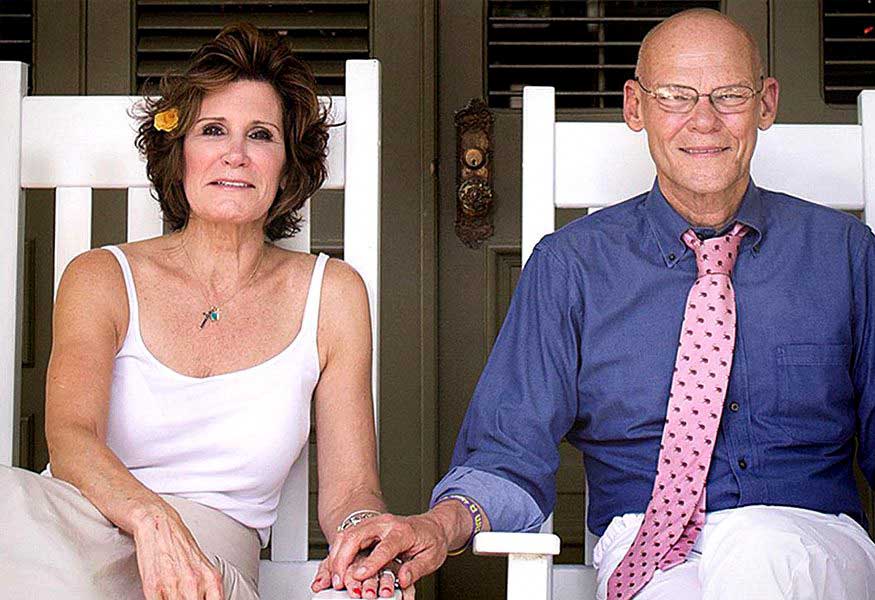

Celebrity couples in politics, such as James Carville and Mary Matalin or Kellyanne and George Conway, have given the politically “mixed marriage” a certain panache—and even a dose of bankability.

Kellyanne and George Conway

But in the bruising era of President Trump, the Weisses’ banter is emblematic of a deep political divide that is breaching the walls of many American homes. “I’ve been in practice 35 years and I’ve never seen anything like it,” says one Washington area psychologist, whose patient load now includes federal employees and spouses in conflict over how best to counter Trump policies. And while vigorous political discourse within families is a long-standing tradition, seldom if ever has a president driven a wedge into the body politic like the one wielded by Trump. His explosive tweets and combative personality—coupled with the heat generated by the Mueller investigation and impeachment—have widened the domestic red-and-blue gulf.

James Carville and Mary Matalin

For Jewish couples, these tensions are often exacerbated by the ongoing arguments surrounding anti-Semitism and Israel, as well as the president’s—and other politicians’—responses to them. The majority of American Jews have identified as liberal Democrats for generations, dating back to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Great Depression, and before that to Jewish labor activism in Lower Manhattan sweatshops. But over time some Jews gravitated to the Republican Party, at first because the GOP offered an alternative to the Tammany Hall Democratic machine. “The spectrum of the parties was much broader then,” says Pamela Nadell, professor of history and Jewish studies at American University. “There were liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats. You don’t have that anymore.” Nadell adds that Jewish conservatism got a major boost from neoconservatives such as Irving Kristol and Norman Podhoretz. But Jews still remain overwhelmingly liberal. Seventy percent are Democratic or lean Democratic, while 22 percent are Republican or lean Republican, according to a 2013 Pew Research study. In addition, about 49 percent consider themselves liberal, with 29 percent moderate and 19 percent conservative.

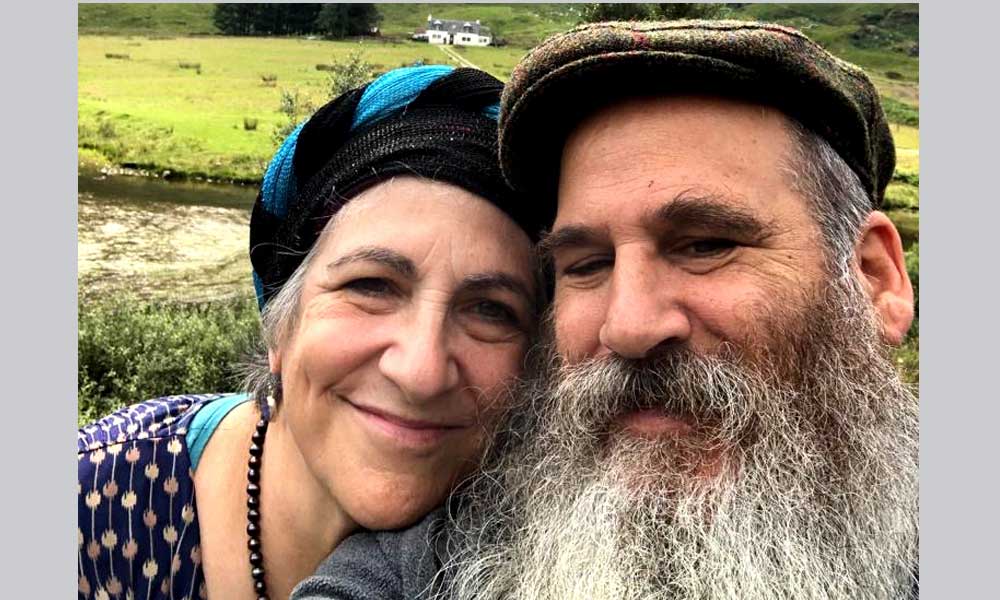

Shoshana and Aaron Shamberg

Orthodox Jews, however, are increasingly moving into the Republican party. More than 54 percent of Orthodox Jews voted for Donald Trump, according to an American Jewish Committee survey, compared to 18 percent of American Jews overall. But differences exist even in the Orthodox world. Shoshana Shamberg in Baltimore says that she and her husband, Aaron, are not on opposite ends of the spectrum “but I am definitely more liberal.” Both are Baal Teshuvha, born into secular families, who became what Shoshana terms “unaffiliated observant Jews.” Shoshana voted without great enthusiasm for Hillary Clinton in 2016 and Aaron voted for a Libertarian candidate. He is a registered Independent and she is a Democrat. Aaron’s father got stiffed in business dealings with Trump, so “our family has always had a big conflict with his ethics in business, and his rhetoric is pretty disgusting too,” Shoshana says. Aaron has grown somewhat more liberal in recent years, and Shoshana has gravitated toward his pro-gun position. He owns several guns and they both go to a target range to practice. “I see now that defense is crucial, which is shocking that we Jews have to face such things in this era,” she says. They both like Trump’s stand on anti-Semitism and his role in the assassination of the Iranian military leader, Major General Qasem Soleimani. For the 2020 election, she says, “we are watching.”

Also following this election closely are Mark and Susan Goldhaber. Mark Goldhaber met Susan Moskowitz in 1983 at a Conservative temple singles’ night in Washington, DC. As young people working for the federal government—she for the Environmental Protection Agency and he for the Department of Housing and Urban Development—they seemed to have a lot in common. It wasn’t until around their fourth date that she realized Mark was not just another career civil servant. “Are you a Schedule C?” she asked, Washington code-speak for a political appointee brought in by the administration of then-President Ronald Reagan. “I had never met a Jewish Republican,” says Susan. “My parents were dyed-in-the-wool Democrats and I had always voted Democratic. This wasn’t the norm I grew up with.”

But it was not a deal breaker. “When he told me, I said ‘OK, but you have to be open minded. We’ll see what happens,’’’ Susan recalls. They married in 1984. Mark, who describes himself as a “pro-growth conservative Republican,” encountered headwinds from Susan’s family early on. A relative of Susan’s greeted him at the door with “I hear you work for Reagan. Shame on you!” Rather than turning away, Susan was sympathetic. “I felt bad for him because I didn’t want him to be constantly defending himself,” she says. “If he had been a non-Jewish Democrat, it would have been easier for them.”

The fact that Mark and Susan lived through the Reagan crucible has helped them survive Trump as well. In 2016, Mark voted Libertarian, Susan for Clinton. Like many conservative Republicans, he supports a number of Trump administration’s policies—particularly on anti-Semitism and Israel. Agreement with Susan in those areas helps to ease some of his rough edges. Nevertheless, “we don’t talk about issues like we used to because it’s too upsetting,” Susan says. The gap between them has manifested itself in unusual ways. These days they watch a lot more home improvement and gardening shows.

Lynne and Steve Toporov

Sometimes conflict emerges gradually. Lynne Toporov grew up in a strong Jewish Democratic household in Northeast Philadelphia and voted twice for Barack Obama. Her husband Steve is a Democrat. They are in their late seventies and are retired in Sarasota, Florida. As the 2016 election approached, Lynne started listening to conservative talk radio and agreeing with the hosts on a variety of issues, from abortion to immigration. On Election Day she did the once-unthinkable: She voted for Trump.

Steve also ended up voting for Trump because he disliked Hillary Clinton. But he soon came to regret his decision. “We don’t agree on a lot of things,” Lynne says. “I’m in favor of Trump and what he’s accomplished. Steve thinks he’s a womanizer and can’t get past it.” (Steve declined to be interviewed for this story. But while Lynne was being interviewed on the phone, Steve could be heard chanting “Vote for Bernie! Vote for Bloomberg!” in the background.) Lynne acknowledges that friends don’t want them to come over anymore, and family gatherings are tough. Once Lynne was told she would have to leave if she mentioned Trump. “My whole life I was always able to talk to anyone about anything,” she says. “And now you can’t. I find that very upsetting.”

Lavea Brachman and Andrew Smith

Lavea Brachman and Andrew Smith in Columbus, Ohio manage to talk about politics despite different views. Lavea, vice president of programs for a foundation, is horrified by Trump and dreads the prospect of his winning re-election. Her husband, CEO of a company that makes paints and resins, generally votes Republican and considers himself a “conservative with a strong dose of late-18th-century libertarianism.” He is not and never was a Trump fan. “There were 16 Republicans running (in the 2016 primary), and Trump was 17th on my list,” he says. Nonetheless, he gives Trump credit for positive developments in the economy. While Democrats condemn the 2017 tax cut as a giveaway to the wealthy and corporate America, Andrew says his company used the lower corporate tax rate to invest in equipment and machinery, and hire more workers. Smith has always enjoyed verbal jousting over politics and compares it to jogging—a form of mental exercise that helps him clarify his thinking. “But it gets me into trouble with Lavea,” he says. “I’m more sensitive about it than in the past.”

Lavea and Andrew’s differences go to the philosophical underpinning of Democratic liberalism and Republican conservatism. In a joint interview, Andrew expressed strong beliefs in the marketplace as a force for economic growth and equity. “I’m always skeptical of government action; sometimes the cure is worse than the harm,” Andrew said. “Those who believe government has the solution to every problem have been proven wrong.” “And I diverge there,” Lavea responded. “I believe in the importance and impact of public policy in areas where the market does not work.” Lavea’s months-long homefront lobbying effort in 2016 led Andrew to cast his ballot for Clinton instead of Trump or a third-party candidate. “I did everything but go into the ballot booth with him to make sure he voted for Hillary,” Lavea says. Andrew says he did so “reluctantly.”

But pairs like Lavea and Andrew may soon be extinct. A massive data-dive and survey in 2018, “The Home as a Political Fortress,” concluded that as political polarization has skyrocketed in recent decades, these kind of political mixed marriages are becoming more unusual. The study found that between 1965 and 2015, spousal political agreement rose by over 8 percentage points, from 73.2 percent to 81.5 percent. In the same time frame, disagreement dropped by a comparable margin, 13 percent to 5.8 percent. That 5.8 percent roughly corresponds to the overall percentage of mixed couples, according to study coauthor Tobias Konitzer. “Couples married 30, 40 years have had a lot of time to adjust to political differences,” says Konitzer, the chief science officer of PredictWise, which helps progressive groups utilize public-opinion data. “For young married couples, this is about choice.” It’s normal for millennials to incorporate political compatibility into online dating apps. Dating platforms now routinely allow users to sift incompatible politics out of pools of possibilities. OKCupid reported a 187 percent rise in references to politics in dating profiles between 2017 and 2018, according to the newsite Axios.

Whether young or old, ultimately, politically mixed couples can stay together if the relationship is otherwise strong and there is mutual respect. For couples like the Weisses, married in 1980, and the Toporovs, married in 1960, the long years together help to keep Trump-era vitriol in perspective, if not totally in check. “Lou is a compassionate, generous and loving guy,” Amy Weiss says. “If anyone can give conservatives a good name, it’s him.” A dash of romance doesn’t hurt. Lou characterizes Amy as “the most beautiful woman that I’ve ever met, inside and out.” And Amy calls Lou “a hunk.” But peace inside the home doesn’t always translate into peace outside. Asked if the schism has had an effect on their social life, Amy responds: “Come to think of it, we’ve been home a lot on Saturday nights.”

Jewish Political Voices Project

One thought on “Mixed* Marriages”

I think a revisit to these interviews would be interesting after the Coronvirus crisis and the presumptive Joe Biden Democratic candidate. It might be very revealing for what’s coming in November.