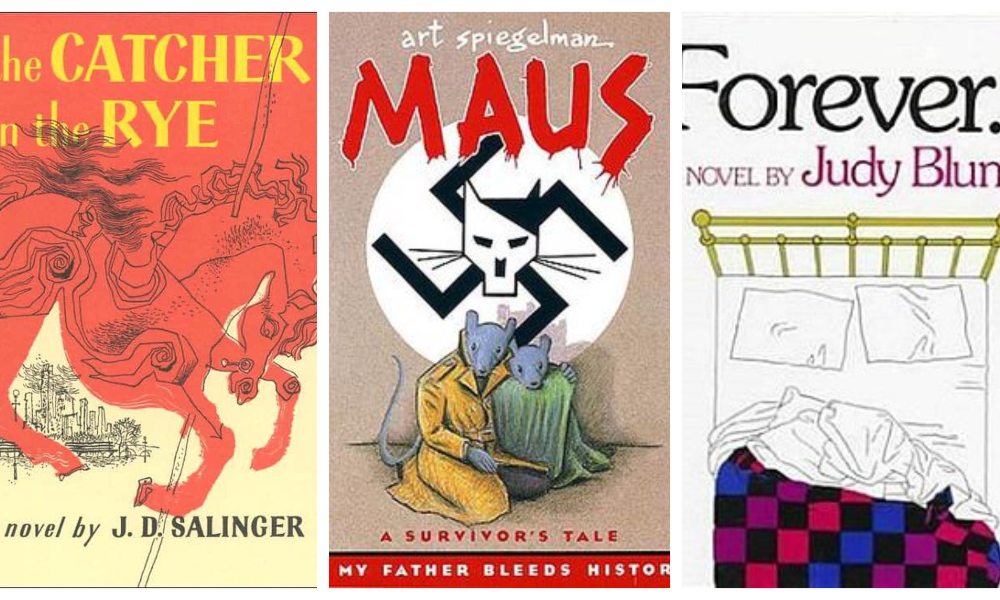

The ‘Maus’ Trap: Famous Banned Books by Jewish Authors

The McMinn County school board in Tennessee did not cite Jewish content or author Art Spiegelman’s Jewish origins when it yanked the graphic novel Maus from the eighth grade curriculum. Rather, the board cited obscene language and nudity—leading a number of people on social media to comment, “they’re mice!” (In Maus, Jews are depicted as mice, Nazis as cats, and non-Jewish Poles as pigs.)

But the question is nonetheless begged: Isn’t the disputed content of Maus, published in 1991, intertwined with Judaism’s greatest historic disaster, the Holocaust? And given the long history of antisemitism and Jewish suffering, is it any surprise that artistic expression of that legacy might yield arguably offensive language and content?

Jewish-American writers represent only a handful of the thousands of authors in recent decades whose books have been challenged or banned. The American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom has documented nearly 8,500 instances of blocking books in American libraries and schools between 2001 and 2020. The ALA, which observes “Banned Books Week” in late September, compiles data of both “challenged” books (ultimately unsuccessful attempts to remove books from shelves) and “banned” books (actual removal).

These are some of most famous examples of banned books by Jewish authors:

The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

Cited as one of the most banned books in the history of American literature, The Catcher in the Rye caused outrage from the moment it was published in 1951. The controversy over its use of profane language, religious slurs and an encounter with a prostitute may have helped propel it to bestseller status. The Catcher in the Rye became a must-read for generations in the coming-of-age bracket. While protagonist Holden Caulfield is a WASPy prep-school boy, Salinger himself was raised Jewish and didn’t learn his mother was in fact not Jewish until after his bar mitzvah. As a successful author and later a recluse in New Hampshire, he embraced a variety of religions and belief systems, including Hindu spirituality and yoga, Dianetics (a forerunner of Scientology) and Christian Science.

Portnoy’s Complaint by Philip Roth

Alexander Portnoy’s tryst with a slab of liver amounted to a page or two in a novel of 200-plus pages. But the outrage over that one episode dwarfed any other deeper analysis of the novel’s merits. It was enough to get the book, published in 1969, barred from some library shelves, and it was famously banned in Australia until 1971. But if anything, the liver scene is emblematic of Roth’s effort to get at the darker side of Jewish growing-up in America. Arguably Portnoy’s sexual hunger is an extended metaphor of guilt and shame over breaking down barriers that isolated Jews for centuries. According to Roth’s obituary in The New York Times, “Gershom Scholem, the great kabbalah scholar, declared that the book was more harmful to Jews than ‘The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.’”

Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark by Alvin Schwartz

Scary Stories, a three-volume series, has the dubious distinction of being the most banned book of the 1990s, according to the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom. Schwartz wrote the stories for children, but he and illustrator Stephen Gammell pulled no punches in depicting horror—whether it’s bloody heads falling down chimneys or a spider infestation on a woman’s face or a grotesque sewer rat turned into a household pet. Jewish literature and tradition has its occult side, although there’s no evidence Schwartz drew on Jewish sources for inspiration. From its publication in 1991 through the early 2000s, schools and public libraries faced major pressure to take Scary Stories off the shelves. Indeed, the series made the bestseller list precisely because young readers couldn’t get enough of the at-times graphic horror, even if the stories induced nightmares. Much like The Catcher in the Rye, attempts to ban Scary Stories only stimulated greater sales. Sadly, Schwartz died of lymphoma in 1992 and never saw his notoriety fully blossomed.

Forever by Judy Blume

With its frank discussion of budding teenage sexuality, Forever was the seventh most banned book of the 1990s, according to the same list that put Scary Stories at number one. Forever slipped a bit in the 2000s to number 16. Blume, who is Jewish, wore the notoriety as a badge of honor. Her books, especially those popular with teenage girls, sold 85 million copies. Forever, published in 1975, follows high school senior Katherine and her love interest Michael. Mostly it surfs the wave of romantic attraction and its undertow of sexual tension. The explicit sex (Michael’s penis is nicknamed “Ralph”) was enough to get the book thrown out of countless libraries and reading lists. Although Judaism does not play into Forever, other Blume books feature it prominently. Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret is about a girl with interfaith parents who doesn’t know which religion to choose. Starring Sally J. Freedman as Herself roughly parallels Blume’s own life, including a temporary move to Miami after World War II because of her brother’s fragile health. (Blume’s father had six siblings, and most of them died while she was growing up; according to the Jewish Women’s Archive, Blume once said, “a lot of my philosophy came from growing up in a family that was always sitting Shiva.”) However, neither Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret or Starring Sally J. Freedman as Herself was subject to the same level of censorship as Forever.

You are important to the conversation. Please contact us at editor@momentmag.com and let us know what you think.

2 thoughts on “The ‘Maus’ Trap: Famous Banned Books by Jewish Authors”

Just a point of clarification

Per the ALA, definitions, McMinn County neither “challenged” nor “banned” Maus, as they merely removed the books from the curriculum and did not even attempt to remove books from shelves

too bad they haven’t read the OLDE TESTAMENT …….. eve is Naked