Jewish Word // Blitspost (Email), tekstl (text), zikhele (selfie) & more

Yiddish: New, Old and Profane

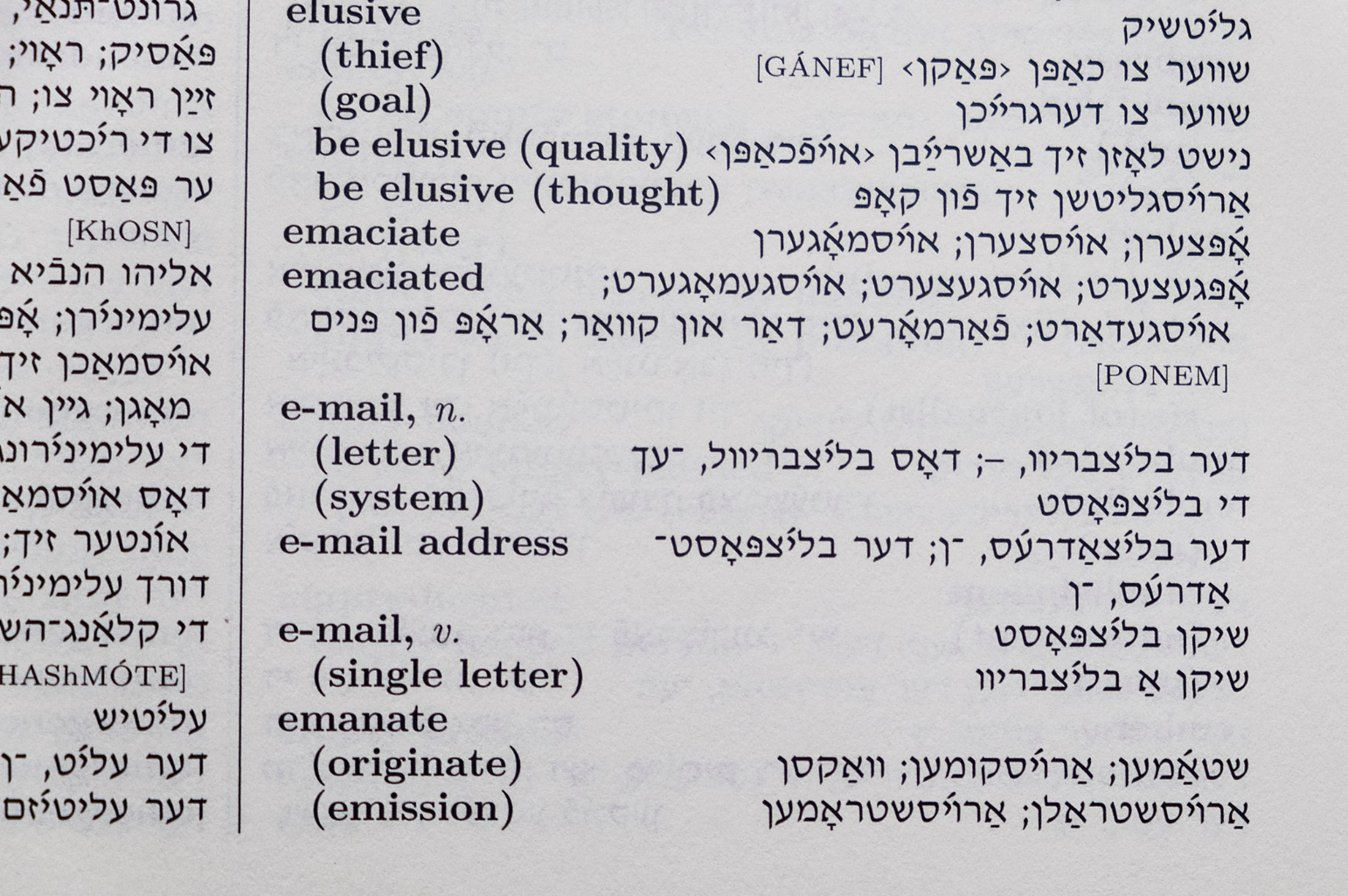

A lexicographic tour de force, the Comprehensive English-Yiddish Dictionary, published this year by Indiana University Press, is an expedition through the layers of a language spoken by rebbes and poets, nurses and prostitutes, schoolchildren and soldiers. Acquaint yourself with the mame-loshn’s multiple personalities: These 50,000 entries are a varied cast of characters.

It’s founded on the life’s work of the philologist and lexicographer Mordkhe Schaechter (1927-2007), who spent nearly every waking moment promoting, standardizing, analyzing and teaching the language; most of today’s academic Yiddishists trace their pedigrees to him. Schaechter collaborated on Uriel Weinreich’s Modern English-Yiddish Yiddish-English Dictionary (1968), and he originally planned a supplement to include words that didn’t make it in. As Schaechter’s collection of words and references grew (comprising thousands of annotated cards by the time of his death), the project began to assume its present outlines: a dictionary of its own, introducing coinages as well as plundering the capacious storehouse of already-existing Yiddish words and phrases. The complete work has caught the attention of casual reader and scholar alike as the largest, most modern and most accessible English-Yiddish dictionary to date.

Two of Schaechter’s collaborators brought the dictionary to fruition: Gitl Schaechter-Viswanath, a Yiddish poet and one of Schaechter’s daughters, and Paul Glasser, a linguist and close associate of Schaechter’s. The coauthors used their judgment (as well as a number of dictionaries in a variety of modern languages) to figure out which Yiddish words to use, or which to invent, in search of the most felicitous equivalents to English terms. I know the editors well and contributed a few suggestions in my field of medicine. To use the dictionary’s words, I hope I am not biased up the wazoo (“het iber der mos,” or “disproportionately”).

Have a senior moment ……… Af a minutkele fargesn

A likely story! ………. A bobe-mayse!

Be in the driver’s seat ………. Firn dos redl; Haltn di leytses; Zitsn afn bretl

Be on top of (an issue) ………. Visn genoy vos se tut zikh

There’s no mistaking what she said ………. Nishto keyn frage vos zi hot gezogt

Is he for real? ………. Er meynt es af an emes?

Up yours! ………. Kh’hob dikh in tokhes! / Valgert zikh op!

While we’re on the subject… ………. Az me redt shoyn vegn dem…

What’s the turnaround time? ………. Vi lang vet (es) gedoyern?

Put up or shut up! ……….Oder shvim oder shvayg!

Many will be tickled by the neologisms, one-word poems at their best and as catchy as advertising slogans: “blitspost” (email), for example, fusing “lightning” and “mail”; or “shilshl-peh” (verbal diarrhea), which makes use of the language’s Hebrew component. No one sent a “tekstl” (text) in the shtetl, nor did Glikl of Hamlin, the diarist of the 17th-century Jewish ghetto, take a “zikhele” (selfie). But it is 2016; Yiddish speakers use “smartfons” (smartphones), even if many religious leaders forbid them. Meyle (whatever)!

When I first open any dictionary, I turn to the obscenities. In this case, there are delightful equivalents for pillow talk (“betshmuesn,” or “bed-chat”) and sexting (“sekstlen”). The f-, s-, d- and c-words have colorful counterparts that can’t be spelled out in a family publication. “Opshpritsn” (or “spray off”) is “shoot one’s wad.” Go and study.

But my favorites are pedigreed phrases that, as a predecessor dictionary put it, hold a mirror up to modern-day English. “Butterflies in the stomach” translates to “se tsitern mir di kishkes” (or “my insides are trembling”). To “bust one’s butt” is to “onhoreven zikh vi an eyzl” (to “work as hard as a donkey”). “The blind leading the blind” becomes “tsvey meysim tantsn” (“two corpses go dancing”).

With this new monument to Jewish stamina and creativity, you can write a learned article, seduce a lover, discuss your taxes, yell at your child, pray with intention or steal from your grandmother. Or do it all: Just gvald geshrign (for God’s sake), do it in Yiddish.

—Zackary Sholem Berger

3 thoughts on “Jewish Word // Blitspost (Email), tekstl (text), zikhele (selfie) & more”

Excellent post. A gantza mechaya to read.

“Are you for real” ……… Du machts sich o du bist!

As Jewish kids in the 50s we never learned to speak the momma loshen Yidish, but we did pick up enough words that we were able to describe others without them having the slightest idea of what we were calling them. It was an important part of our Jewish youth.