Interviews by Sarah Breger, Ellen Wexler and Anis Modi| March/April 2019 | Big Questions

Millennials are not like other generations. Or so we are told. Defined by the Pew Research Center as anyone born between 1981 and 1996, millenials are now the world’s largest living generation. In Jewish life, millennials have shown themselves to be less interested in joining Jewish institutions or observing Jewish rituals, and more distant from Israel than their parents. The 2013 Pew survey of American Jews found that 32 percent of millennials self-identified as “Jews of no religion.” But when we asked 18 millennials to describe how their Judaism and Jewish identity diverge from that of their parents, a more complex picture emerged. Of course, no sample this small can be representative; nor is it likely to capture the young people who’ve left the community behind (or, left Judaism behind entirely).

But we found a group who feel deeply Jewish—even as they also value other parts of their identities. They are at home in multiple worlds and proud of it. And like generations before them, they are evolving: For some seeing the rise of the alt-right and encountering anti-Semitism for the first time has led them to reconnect with their Jewishness; for others parenthood has enhanced their commitment to their faith and heritage. They value text study, have reimagined rituals and enjoy celebrating Shabbat—although often differently from the way they were raised. We think you’ll enjoy meeting them.

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]Eve Peyser, 25[/custom_font]

Credit: Elizabeth Renstrom

My parents didn’t raise me with much awareness of my Jewish identity, or what it meant to be Jewish. As a kid I had this impulse to reject religion and tradition, so when people would ask me, “What’s your religion?” I’d say, “Oh, I’m an atheist,” but note that my grandparents are Jewish. My mother is the child of two Jewish refugees—my grandmother was from Austria, my grandfather was from Germany. They sought asylum in Australia in 1939, and my mother was born there in the 1950s. Her mother never really imparted much about the trauma of having to leave Vienna. My mom moved to New York in the 1970s, where she met my dad, who is the child of second-generation Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe.

Jewish identity wasn’t something I thought about much. I grew up in New York City, where it was normal to be Jewish. Throughout my childhood, I went to a lot of lavish bar and bat mitzvahs, so I associated Jewish identity with an upper-class culture that I didn’t have access to. There was this idea that Jewish people are very privileged and oppressors in some way, which made me feel alienated from my Jewish identity.

When I went to Oberlin, I started thinking about it more. On campus there was a lot of pro-BDS activism, a culture of extreme leftism and radical college politics. My parents don’t support the Israeli occupation, and we’ve always been quite critical of Israel. The campus politics made me feel embarrassed about my Jewish identity.

But after I graduated, especially when I started writing about politics in 2016, I experienced a fair amount of anti-Semitic harassment online, like many other Jewish journalists. I realized that I can’t escape being read as Jewish, nor did I want to. This is an inescapable part of my identity, and it’s something I’m going to receive abuse for. The persistent myth about anti-Semitism is that it doesn’t exist, and that Jews don’t experience violence based on their religion and ethnicity. That’s just not true, especially in the Trump era. We had this deadly synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh; conspiracy theories about Jewish people run rampant. Anti-Semitism has not gone anywhere, and because of that, the way I understand my identity has changed. It almost inadvertently made me feel proud of who I am, because I want to push back against all of those violent stereotypes. For me, Judaism is still more of a cultural affiliation—reading great Jewish authors like Philip Roth and Hannah Arendt, learning how to make Jewish food that I love, having Jewish friends and talking about our identities with each other.

To me it’s not religious at all—especially since Jewish culture here in New York is so vibrant. And even though I don’t really have a Jewish community, over the past couple of years I started to very strongly identify—I’m a Jew. It’s not something that I push into the back of my mind. Regardless of my past feelings, this is who I am.

Eve Peyser, 25, is a writer and producer at VICE.

______________________________________________________________________

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]Alissa Thomas-Newborn, 30[/custom_font]

Credit: Shulamit Seidler-Feller and Maharat

My Judaism and my parents’ are surprisingly very similar and very different all at once. My parents are both spiritual people who are deeply connected to Judaism. My mom is a Reform rabbi and cantor who raised my brother and me with a strong focus on belief in Torah and Hashem and observance of mitzvot. When I started to define my own relationship with Judaism, I ultimately found my spiritual home in Modern Orthodoxy, but the truth is that my beliefs and observance feel like an extension of how I was raised. I have embraced all my parents taught me—most profoundly their strong love of God and their faith in God’s hand in our lives—and have built a home that is my own and a continuation of theirs.

Now I’m really working in my dream job. I get to serve God and His people, and I am very blessed that I live at a time in history when I can do all that my job entails. I love learning, teaching, providing pastoral care and being with our community members in moments of joy and, God forbid, sorrow. It’s avodah—holy service—more than “work.” And my own relationship with Hashem is deepened through it. Orthodox Judaism has always had space for learned spiritual women to lead, and my job is an extension of that. There have certainly been tough times, but it’s all been worth it. And Baruch Hashem, my parents are so proud of me! Judaism exists in so many beautiful forms in my family—Orthodox, Reform, Conservative, Reconstructionist and cultural—and we all love each other. My family supports me in serving God in the way that is right for me. And we try to look at the differences we have as opportunities to learn more and connect more.

Alissa Thomas-Newborn, 30, a rabbanit at B’nai David-Judea Congregation, is the first Orthodox woman to serve as a clergy member in Los Angeles.

______________________________________________________________________

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]Abby Stein, 27[/custom_font]

I grew up in Williamsburg, in the Hasidic community where Judaism is your entire life. From the second you wake up to the second you go to sleep, from the moment you were conceived until the end of the shiva, everything is determined. The way you go to the bathroom is regulated, the way you dress, what you’re supposed to talk about and what you’re supposed to do. I struggled a lot growing up. Since I can remember, I identified as a girl. In that community, gender is a huge part of who you are. Men and women don’t interact at all, unless you’re in a huge family. There are radically different roles for boys and girls. I was married when I was 18, and then when I was 20, my son was born. With fatherhood, gender again felt so prevalent. At that point I was going to go down a very similar path as my father had and become a rabbi. And that became really hard when I was questioning my whole identity, and as a result also questioned a big part of Judaism.

I left religion at 20, and I remember exactly the Shabbat that I used my phone: It was January 2012, seven years ago. That was a really big deal for me. At that time, I was done with Judaism—not just Hasidic Judaism. I didn’t want to have anything to do with it. In 2013, my idea of celebrating Yom Kippur was arranging a camping trip for a bunch of people who also grew up Hasidic and had left. And everything on the menu was pretty much made out of pork, which was just our way of saying, “Fuck you, fuck everything and we’re just going to do this.” Slowly, though, there was this realization that there were parts of Judaism that I missed. I started reading and I remember the first book of what I call modern Judaism that I read was Judaism as a Civilization, Mordecai Kaplan’s book. This was the first time I was aware that there are liberal and progressive Jews. I also started really falling in love with Shabbat, but a very different kind of Shabbat from the one I grew up with. If you asked me if I observe Shabbat, I would say no; if you asked me if I celebrate Shabbat, I would say yes.

About four years ago, before I transitioned, I was going through a lot of struggles, and I decided that every Friday night I’m going to do something. For a lot of people who have been through depression or really hard times, one of the biggest problems they have, and I had, was getting into this zone of weeks—sometimes months—where you don’t interact with anyone. And once a week, I’m forced to make a short stop and do something different and go out and be with people. Whatever that is—going to a service, going to a meal, just going out with friends—I’m going to do something to celebrate Shabbat. Yes, I’m going to use my phone and watch TV, because that doesn’t seem like a contradiction. That just seems perfect to me. Growing up we would make fun of all these people who change the traditions and decide what they do and what they don’t do. Even in the more progressive world, people almost have these expectations where there’s a straight line of observance, and there are all these bullet points. But I take some things that are radically Hasidic and celebrate those at the same time as I’m being totally secular—and it doesn’t just feel okay, it feels beautiful.

Abby Stein, 27, a transgender activist, is the first openly transgender woman raised in a Hasidic community. Her book, Becoming Eve,

comes out in November.

______________________________________________________________________

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]Jeremy England, 37[/custom_font]

My Judaism is an idealism derived from the Torah and built on top of an ethnic and national sense of identity that my mother experienced growing up. My mother was born in Poland right after World War II and lived there until the age of 10. Although she didn’t have a religious upbringing, she’s always been very confident about her Jewishness as a national identity. Growing up as an American kid in New Hampshire, I knew I was a Jew but also knew I could never be Jewish in the way that she was. When I was studying in the UK during graduate school, it was the first time I had moved away from the Boston area and outside the protective bubble of home. I encountered so much hostility to Israel, and it just woke me up to the point of saying, I have to decide what this means to me, and if it matters to me, because it suddenly felt like a very high-stakes game. Discovering that there was still so much animus toward the Jewish people in the world was the first thing that really struck me. Even though I didn’t know what was going on in Israel, I instinctively had a strong sense of closing ranks and just wanting to protect Jews. I visited Israel, and I fell in love with the land and learned the language. As a result, I also read Tanach and Talmud, which felt like an unparalleled intellectual opportunity to me. I drank deeply of Torah and became very addicted to it.

For me, Judaism is a set of tools for approaching the deepest questions of the human condition. There are things that I love and cherish about the traditions and the customs, but what I’m ultimately compelled by are the ideas about how to relate to the Creator of the world, how to serve Him and how to keep the covenants that are laid down in the Torah. One of the wonderful things about the peculiar trajectory that my life ended up taking is that I had reached adulthood as a scientist before taking any interest whatsoever in the texts or tradition. As a result, I came to the Torah not wanting to give up on science. I made a choice to say, this is a covenant that was given to the people of Israel by the creator of the world. He knows all that I know and more. When some things seem kind of hard to square, then I am the one who needs to work more. I think that maintaining a discomfiting intellectual tension, and not resolving the tension by rejecting God or rejecting this letter or that word in Torah because it must be a mistake, was possible for me because of where I was coming from. From where I stand now, I know this insistence on the truth of the Torah helped me climb to heights of understanding I wouldn’t have been able to reach otherwise.

Jeremy England, 37, an associate professor of physics at MIT, is credited with creating a new theory of the physics of lifelike behavior.

______________________________________________________________________

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]Gaby Dunn, 30[/custom_font]

Credit: Doug Frerichs

My parents were not that religious until I was in the third grade. My dad was an alcoholic and a drug addict, and my mom wanted us to become religious so that he would get sober. She thought if we leaned into Judaism and became real Jews, it would motivate him. In some ways, maybe it helped, but I think it was a false equivalency. He didn’t get sober until I was 17. So I don’t know how much of an influence it had. My mom found a synagogue when I was nine and joined, and she threw herself into it. She was like, “This is great. I love this. I’m friends with the rabbi, I’m taking adult education courses and I’m learning all this stuff.” Then she moved me from public school to a Jewish day school. Both my parents served as presidents of the temple, and they brought a bunch of people over and koshered the kitchen. They changed from being very hippy-dippy Florida redneck to very, very intensely Jewish. It seemed like it happened in the blink of an eye, but I think it was over a few years. There wasn’t a lot of thought put into, “I wonder what kind of Judaism they’re teaching.” We were at a Conservative synagogue that shared a building with an Orthodox synagogue. We had a male rabbi, a male cantor. The cantor’s wife and the rabbi’s wife were expected to do certain things like setting up food and cleaning. It just read to me as a very patriarchal system.

Spoiler alert: I ended up gay. When I was in middle school and high school, there was a lot of stuff that was like, “Don’t have sex, and also don’t be gay.” It was worlds away from when I would go to friends’ synagogues that were Reform or Reconstructionist and say, “Oh, there’s a woman rabbi.” Or, “Oh wow, that’s the cantor and her wife.” So by the time I was around 15, I was like, “I’m an atheist and I hate everything.” I fought my parents on everything and didn’t want to do confirmation. My sister ended up transferring back into public school.

My parents are still very Jewish, but they have relaxed a little bit. My dad actually did get sober of his own accord, so it became less dire that they be so super Jewish. And by the time I was 19 or 20, I was like, “Okay, I don’t hate it.” I had all of this knowledge: I knew the songs and the prayers. I started getting closer to my grandmother, who was a Holocaust survivor, and I met other LGBTQ Jewish kids. Now I feel it would be like renouncing an ethnicity to reject Judaism. I make all the foods because those are the foods I know how to make. Or I speak a certain way because those are the words I know. The Jewish star necklace comes back on, the one I got at my bat mitzvah—I still wear it. It’s interesting now where Judaism comes up. My girlfriend is the biggest goy of all time, but we do Hanukkah and we got a little Hanukkah sweater for the dog. We don’t have a kid—we don’t have any plans to have a kid at any point—but I once said, “Well, at our future child’s bat mitzvah…” And my girlfriend was like, “Why would they have a bat mitzvah?” And I don’t know if my mom just put a tip in my head, but I was like, “Oh, she’s having a bat mitzvah.” She doesn’t exist; she’s not a real child! I’m 30 now, so it’s been interesting as I get older, realizing what I had taken for granted as being a thing. I’m not a synagogue-going Jew, but I acted like it was the craziest thing my girlfriend ever said, that our nonexistent child wouldn’t have a bat mitzvah. So I don’t know how it got so deep, but it’s in there.

Gaby Dunn, 30, is a comedian and the host of the “Bad With Money” podcast and co-creator of the YouTube show Just Between Us.

______________________________________________________________________

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]Jared Jackson, 36[/custom_font]

Credit: Sasha Aleiner

My family framed Jewish identity in a way that emphasized how a lot of Jewish values are humanistic. We saw them as cornerstones of our humanity rather than as a separate space. My mother’s side is from Russia and Poland and comes from a long line of Hasidim, and my father’s side is African American from South Carolina and Philadelphia. My father passed away very young, and my mom tried her best to keep us a part of the Jewish community and religion. At home we did certain things, like always coming home for Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah. After 13, I started fasting on Yom Kippur. Our version of Yom Kippur was fasting and watching Sanford and Son reruns, or Good Times—basically black television and fasting. Laughing really hard and fasting don’t really go together, but it was what we did.

While we kept certain traditions at home, it wasn’t as safe for us to be in the synagogue because we looked different. In some places it was overt racism, even from rabbis and in the synagogue. At others it was more covert, where we were being told that we might not “fit what the community is looking for” or that “we can’t have you here because you will impact our image.” I must have been five or seven, and I remember vividly all the things that were said. We weren’t physically kicked out of synagogue, but I was told and shown from an early age that me being Jewish in the body I inhabit was not allowed. That happened in all of the six or seven places around us that we tried to go to.

Now I belong to two synagogues and a minyan. My kid goes to preschool at one, and the other two are just a short walk away. It can still be a difficult experience sometimes. The pervasive nature of racism and bigotry that still lives in Jewish culture is there. I sometimes have a really hard time connecting spiritually because I’m worried about what might happen, like some clearly racist members of the synagogue trying to silence me when I speak up or making derogatory remarks. But today I have more tools to deal with these situations. My Judaism has always been tied to interactions with fellow human beings. As far as identifying as Jewish, I don’t use one label or another, but being Jewish has always been a deeply rooted part of my identity. I feel like more and more people are moving away from labels. I’m seeing more and more Jews of color, multi-heritage Jews, as well as mixed families, claiming what’s rightfully ours. And while some organizations have programs for Jews of color and some organizations are moving toward integrating Jews of color into their actual leadership, it hasn’t made it to leading organizations in our community yet. The community has to realize we are not a program, we are a people.

Jared Jackson, 36, is the founder and director of Jews in All Hues, a group advocating for inclusion of dual-heritage Jews in the Jewish community.

______________________________________________________________________

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]James Kirchick, 35[/custom_font]

Credit: Niels Blekemolen

My Judaism is probably more Israel-focused than my parents’. Israel wasn’t as much of a disputed issue in the United States among young people when my parents were growing up in the era of the Six-Day War. But I was in high school during the Second Intifada in 2000 and Israel was in the headlines all the time, so I was forced to learn about the conflict. I was becoming very politically aware at that time in general, and then Israel became this major geopolitical issue, which I recall being very formative for my own political development and development of my Jewish identity.

My views on Israel and my views on a lot of issues are sort of old-school liberal views. They’re views that liberal Democrats, like Scoop Jackson, held. But today, I think a lot of millennial Jews are estranged from Israel; they don’t understand the history of Israel, the history of the conflict. It’s sort of an annoyance to them. There’s this Jewish country and it has this problem with its neighbors, the Palestinians. And it’s sort of embarrassing, as liberals and leftists, to have to be associated with this country that is portrayed as a colonial occupier. If you actually spend time studying the history of the conflict, you realize how erroneous and unfair this categorization is. I think it’s really just an ideological laziness. A lot of young, left-wing Jews have been privileging their ideological leftism and their desire to be liked by their peers on the left at the expense of truth and justice and what’s right. There’s this whole movement to disassociate from the State of Israel, and I don’t buy it. I don’t think you have to choose between being a liberal and being a Zionist; I think they’re both perfectly compatible. And if the government of Israel now happens to be right-wing, it’s because of the failures of the left in that country and the fact that the left doesn’t speak to that many Israelis anymore.

Anti-Semitism is also becoming more of an issue for me, strangely, than it was for my parents. Obviously they were growing up at a time when it was probably harder to be Jewish. My parents went to college in the late 1960s, and they were just at the end of the era of quotas in the universities. It was more of a genteel anti-Semitism back then, of the country club and the Ivy League schools. It wasn’t like what happened in Pittsburgh, and it wasn’t like what’s been happening in Europe over the past 15 or 20 years. I never felt more aware of being a Jew than when I lived in Europe. It’s not something that you really are forced to confront living in America as a secular Jew. Obviously if you’re Orthodox, it’s a different story. But as a secular Jew living in America, growing up in Boston, going to Yale, working in Washington, DC, for The New Republic magazine—none of these are environments where you’re really made to feel out of place as a Jew. You expect that you’re going to be treated as an equal. In Europe, it’s completely different. You are made immediately to feel like an outsider.

James Kirchick, 35, is a journalist and a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution. He is the author of The End of Europe: Dictators, Demagogues and the Coming Dark Age.

______________________________________________________________________

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]Lahav Harkov, 30[/custom_font]

Credit: Michael Alvarez-Pereyre for Nefesh B’nefesh

The difference between my parents’ Judaism and mine is that I live in Israel now. I made aliyah when I was 17. In Israel, Judaism permeates everything. It’s part of life, whereas in the United States you have to make an effort to have it in your life. One example is that, growing up, it was important for my parents that we wouldn’t intermarry. In Israel it’s still important, but also kind of a non-issue because the chances that a Jewish religious person here would intermarry are very small. In communities outside of Israel, Jewish institutions are the centers of Jewish life. In Israel it’s not like that. Jewish life is everywhere. So you don’t have to specifically join a place and pay your dues to be part of the Jewish community like in the States.

Another difference between my parents and me is that I grew up being Modern Orthodox, whereas they came from a less religious background. Because of that, they tend to be more strict about the exact details of the practice of religion, whereas for me it’s less important. I definitely consider myself Modern Orthodox and live within that traditional framework, but I don’t get hung up on any details. I think fitting into the box of the community has been more of a concern for them than it is for me. As far as practice and how it affects my day-to-day life, Shabbat is non-negotiable. I turn my phone off. I do read newspapers, but I don’t work or write. I observe Shabbat halachically and I think it’s beautiful, because I get to spend time with my family. Part of the advantage of being in Israel is that my employer understands that. Even when I was managing the Jerusalem Post’s website, which is a 24/7 job, I would have plans for what other people should be doing but made sure that I could disconnect.

Outside of that, I am Orthodox, but I’ve always been on the liberal end of Orthodoxy, which can be difficult in Israel. I know there are other people out there like me, but there aren’t many institutions that reflect that way of life. I have a two-year-old daughter. I hope that by the time she is in school, there will be more humanist and more feminist values about treating women more equally in Orthodox institutions. The place of these values in the Jewish experience has always been an issue for me within Orthodoxy. There’s nothing that my daughter loves more than Shabbat. Every time she sees candles, she covers her eyes and thinks it’s Shabbat. Being a parent adds a whole other level of meaning to being Jewish. I learned a lot from my parents, and I hope I’m going to impart that knowledge to my children.

Lahav Harkov, 30, is A Senior Contributing Editor at The Jerusalem Post.

______________________________________________________________________

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]Ben Lorber, 30[/custom_font]

My parents were proud to be Jewish, but Jewishness was more of a cultural habit (bagels and lox, Seinfeld). We belonged to a Conservative synagogue in the suburbs of Washington, DC, which my grandparents had helped found, and we would go to shul on High Holidays. I went to Hebrew school, was bar mitzvahed and went to a nominally Jewish summer camp; but besides that, Jewishness was not a big part of my family life or identity.

In college I found myself drawn to Jewish thinking and Jewish philosophers. I had friends who became baal teshuva and were more religious and they convinced me to come to Israel and spend a couple of months in yeshiva, where I deepened my Jewish identity and developed a strong connection to the land of Israel. In the years since, I’ve grown my Jewish learning and observance, been part of many vibrant Jewish communities, made Jewish music and am today applying to rabbinical school. It’s interesting how, in my generation, many of us have ended up becoming more Jewishly engaged than our parents!

While in Israel, I also spent time as a journalist and activist in the West Bank, and I came face to face with the reality of Israel’s occupation and ongoing denial of Palestinian rights. As a Jew committed to the pursuit of tzedek and tikkun olam, I found it painful to realize that these injustices were being committed against the Palestinian people. I was also angry that I wasn’t taught any of this growing up, in a Jewish community where too often, we were only presented with a surface-level, one-sided understanding of the conflict, and it was assumed that if you are Jewish, you support Israel—no questions asked.

Back in America, I became a part of a growing movement of young American Jews who demanded an end to Israel’s occupation and deep-rooted injustices against the Palestinians. We are very proud to be Jewish, and we are also very proud to support Palestinian rights. This led me to work for Jewish Voice for Peace for several years as their campus coordinator and to become a member of IfNotNow.

For me, and for many of my generation, being Jewish is about engaging with our rich histories, rituals and traditions; grappling with our legacies of trauma and resilience; standing against anti-Semitism and all oppression; and wrestling, compassionately and bravely, with the vital issues facing our people—including the moral crisis in Israel/Palestine. We hope, we pray and we work for a just peace that feels ever more elusive every day.

Thankfully, my parents have been generally supportive of the many novel paths, religious and political, my Jewish journey has taken. They had always supported Israel by default, without thinking about it that much—and while they haven’t always agreed with my activism, they listen and engage, and we learn from each other.

With my grandmother, our Israel conversation has been harder. For her generation, Israel was the phoenix rising from the ashes after the Holocaust—the David, never the Goliath. While she is also very liberal—certainly no fan of Israel’s emboldened right wing—it was hard for her to stomach my fervent, vocal activism. The issue was especially fraught because she and I share a deep Jewish connection, a love of Hasidic lore, progressive Jewish culture, Yiddish and Jewish song.

For years, there was pain and frustration between us. But gradually, we have come to a greater understanding. I have worked to understand what Israel means to her and her generation. She has developed a deeper understanding of how my activism is rooted in Jewish love and pride, a Jewish yearning for justice and peace. Building this open-hearted, honest understanding between generations is vital for Jewish communities right now, as we grapple with the deepest issues facing our people, and work to build a renewed future.

Ben Lorber, 30, is a writer, researcher and former campus organizer at Jewish Voice for Peace.

______________________________________________________________________

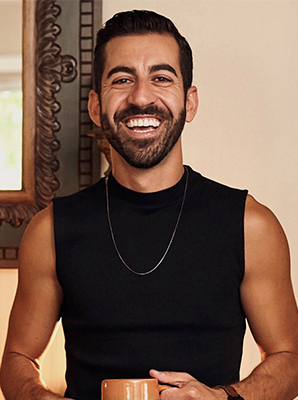

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]Arya Marvazy, 32[/custom_font]

For Iranian Jews, Shabbat is our Torah. That’s always stayed a consistent, powerful element of our Judaism. And that consistency is beautiful. When I was younger, I remember struggling with, “Why can’t I just go out?” I remember when I was 16 sitting at my grandmother’s house, being with my family, and a lightning bolt hit me, and I realized that I’m lucky to have this. To this day I text my mom to see what they’re doing for Shabbat before I make other plans. My parents both keep kosher, my brother, sister and I don’t.

Many Iranians also feel that their Persian identity is inseparable from their Jewish identity, and they always make sure to say they’re Persian-Jewish. When my family came here after fleeing the Iranian revolution, they found it comforting to be embedded in this community in Los Angeles that still had some feeling of home. Growing up, that was very true for me. My identity as a Jew also centers around my Mizrachi identity. At the same time, I’ve felt that otherness of being Persian when institutions, organizations or even individuals make the assumption that the Ashkenazi way is the most normal, organic, widespread way to think about Judaism. I do feel very lucky to be in this generation, because the conversation about “ashkenormativity” has been happening for a while now.

The messages in the Jewish community and from my parents were very traditional, and their understanding of LGBTQ identity and community was limited. So being gay, I never had any role models or examples of people who were like me and were out. So inadvertently the message was I wouldn’t be able to be me if I stayed in the Jewish community. But I have always had a rich Persian-Jewish circle, and in college my circle and I started building a Jewish life that was relevant to us. That was the catalyst for an exploration of my Jewish faith and identity. As I engaged more, I began to embed Jewish learning on a weekly and monthly basis, I explored my identity as a Jew, and I really tuned in to it. While in my youth, Judaism was more of a cultural idea; over the last ten years I’ve explored it through adult learning, Kabbalah, reading texts and working with organizations. I’ve independently pursued a richer understanding of Judaism, and I now experience it in a much more significant way. What deeply informs me in my work is my focus on tikkun olam and the idea of “justice you shall pursue.” My whole life as an activist has been built on the feeling that, in my role as a Jew, I’m responsible for making the world a better place. Working for a Jewish LGBTQ nonprofit, my Judaism is never separated from my daily life.

Arya Marvazy, 32, is a first-generation Iranian-Jewish American, an LGBTQ advocate and a Jewish community organizer.

______________________________________________________________________

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]Marisa Michelson, 36[/custom_font]

My father comes from a very strong cultural Jewish background. He grew up in Brooklyn, and I’d say he is a very typical traditional-cultural-atheist Jew. My mom grew up Methodist and chose to convert to Judaism. She actually converted to Judaism the day I was born—she had just left the mikvah when she went into labor and rushed to the hospital. I grew up in what I consider an atheist household, but still with Jewish culture as a central element of life. We did all of the large Jewish holidays, the High Holidays, Passover and Hanukkah, but also celebrated Christmas and Easter. There were times when we did Shabbat, but it wasn’t a consistent, regular occurrence. On the other hand, my father is very situated in the Jewish community as a poet and a writer and the owner of an art gallery. He recently won a National Jewish Book Award, so I’d say a lot of his work has always been centered in Jewish culture.

I went to Sunday school for a little while. Having a bat mitzvah wasn’t a given for me, but I remember talking to my parents and telling them that I wanted one. Initially, it might have been part of the fact that it goes along with having a party. But learning the chanting and the singing turned out to be a meaningful experience. Standing there during the service was a transcendent moment where I felt fulfilled and had a sense of a deep connection to Jewish faith and tradition. I remember thinking, after the ceremony was over, that I didn’t need a party anymore because that was enough for me.

I’ve always felt that the remembrance of the Holocaust was a part of my Jewish identity. There were books everywhere about the Holocaust, and I feel like I read every Jewish children’s book about it. It cultivated in me early on an understanding of the Jewish experience and of being oppressed, but also a deep sense of empathy and compassion. When I was 12, I played Annette in an opera called Brundibar, which had been performed in the Terezin concentration camp, and I played Anne Frank in the Meyer Levin stage version of her diary a few years later. I got to meet Holocaust survivors, and the feeling of carrying the torch of these stories was significant for me both as a Jew and as a human being.

My Judaism has always had something to do with the music, too. The songs that were sung in congregation struck a deep chord within me that always felt so natural, alive and full. The music inspired me, and I feel that it entered my blood in a way that felt like drinking a glass of water—it was nourishing and beautiful. In my work I’ve drawn stories from the Torah to make my musicals and compositions. One of my favorite pieces I’ve composed is “Song of Song of Songs,” obviously based on the “Song of Songs.” That text is something that intrigues and feels familiar to me.

I feel that I have enough ownership of it that I can interpret it.

There’s a groundedness and sense of family that I get from my Judaism. It is also a way to interpret the world, because it has a great wealth of space for questioning and critical thinking. I’m a seeker; I love learning and I’ve always had a deep spiritual longing. I’ve explored many different texts and cultures over the years, but Judaism has always been my home.

Marisa Michelson, 36, is an award-winning singer, composer and writer of interdisciplinary music-theater performances.

______________________________________________________________________

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]Adam Serwer, 36[/custom_font]

Credit: Shawn Theodore

My paternal grandmother extracted a promise from my mother before we were born that we would be raised Jewish, which was partly rooted in an argument over conversion. My mother refused to convert (though she eventually did, right after my bar mitzvah), and the compromise was that my brother and I would be raised Jewish and bar mitzvahed. My parents raised me with a Jewish identity and the understanding that that meant something. And that’s never been in question for me, which is in part why I always found the barriers of exclusion that we ran into so absurd. One way to fulfill the “assimilation will lead to the destruction of the observant Jewish population” argument is to exclude Jews who are interfaith, who actually want to be Jewish and want to be part of the community, as opposed to just having a secular identity. It took a while for my family to find a congregation that would accept us as an interfaith family. My brother was bar mitzvahed at a Reconstructionist synagogue, after other congregations would not accept him.

My father was in the Foreign Service, so we lived abroad for a significant portion of my childhood, in places that didn’t have Reform congregations. I did have a bar mitzvah, I did read Torah. But I also had to deal with anti-Semitism fairly early. We spent a significant amount of time in Italy, and I very distinctly remember being told that I had killed Jesus, and things like that.

Now I would say that my observance isn’t super different from my parents’. They go to temple on Fridays more often than I do, although I go more than twice a year for the High Holidays. Probably the only real difference is that I try to avoid pork and shellfish, and meat and cheese, and my parents absolutely do not care. I don’t have separate silverware or anything like that. I just try to avoid consciously eating it.

As a biracial Jew, there have also been moments when people treat you like you don’t actually belong there. Those are rare, but they happen enough that I remember them. Part of it is a kind of benign ignorance—“Oh, are you Jewish?”—you get that question. For the most part, it’s that kind of stuff. People trying to exclude you because your mother’s not Jewish, or because you’re a curiosity.

Today, the rise in anti-Semitism has brought up a lot of memories. I would say that the current climate has provoked a civic impulse in me. Precisely because it feels like there are people who don’t like the fact that I’m Jewish, I want to make a point of it. I don’t think that’s about religious observance. It’s about asserting identity.

Adam Serwer, 36, is a staff writer at The Atlantic covering politics.

______________________________________________________________________

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]Dana Schwartz, 26[/custom_font]

We were Reform growing up; I was bat mitzvahed, and that was really important to my family. My parents were pretty regular in attending services and observing certain traditions. Today, I think I’m less—maybe rigorous isn’t the right word—probably less formal in my practice. Part of my career path means I’ve been moving around a lot, and it’s been harder for me to find a Jewish community, and it’s also harder for me to get home to my family to celebrate some holidays.

But I also think that, as part of my career path, I am always surrounded by cultural Jews, and I’m engaging in the social side of it. So maybe even though my Judaism is less formal and ritualized, I’m just as culturally engrossed as my parents were. As an adult, being able to find a Jewish community is not something I take for granted. It’s something I’m really grateful to my parents for, for instilling a love of tradition and the importance of those moments of ritual.

But also, more so than my parents, I’m someone who works with part of my identity public facing. When I worked for the Observer, owned by Jared Kushner’s publishing company, I wrote an open letter to Kushner about the anti-Semitism in Trump’s presidential campaign. I really just wrote it out of pure fury at the time, just in a fugue state. I was shocked and furious and gaslit by the entire campaign, which either ignored or sort of winked at those forces and people. The harassment I received in response was beyond anything that I knew existed. You know in the abstract that it exists obviously, but I had never internalized it in that way. I think it further entrenches me in my pride and cultural heritage. Being true to my own identity is something that’s really important to me. Being Jewish is not something I ever am able to hide, both in my face and my last name, nor is it something I would ever want to hide.

Dana Schwartz, 26, is a correspondent for Entertainment Weekly and the author of And We’re Off and Choose Your Own Disaster.

______________________________________________________________________

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]Elad Neohrai, 30[/custom_font]

Like many Jews, I grew up culturally Jewish. My parents are Israeli, originally from Kiryat Gat, so they grew up in a typical, secular Israeli mindset. I grew up in the suburbs of Chicago, which is similar in that it’s culturally Jewish but religiously pretty secular. Probably the most religious experience for me back then was having my bar mitzvah, but that was pretty common in Jewish communities that aren’t really religiously observant. You spend the year going to a million bar mitzvahs, and that was it.

When I went to Arizona State Uni-versity, I started going to Hillel early on, and spent a year after graduation going to the local Chabad. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with myself, so I went to a yeshiva for baalei teshuva (those becoming more religious) in Israel, and that’s where my journey to Orthodoxy started. Two things really attracted me to Judaism: the belief and the practice. The belief system that I was attracted to is Chassidus. I think Judaism can be all-encompassing, but what interested me are the parts that deal with mystical ideas and things that are less based in the day-to-day. You can say it’s the big questions, like what is God? and why are we here? I always wanted to know more about these topics, but felt like I had no system to address them. So to have tools that help me engage these questions on a spiritual level is really powerful. One practice I really love is farbrengen, a Hasidic tisch. It’s usually an experience where a bunch of hasidim get together, sing and talk about deep spiritual ideas, and try to elevate each other through this practice, and it’s meant to reach a higher spiritual level than one can get to on his own. Now, I run these things called creative farbrengen in my home. Creativity is my access point into Judaism.

When I started my journey into Orthodoxy, my parents were a little nervous. They were a bit suspicious, but I think that once they saw I wasn’t going crazy they were supportive. My mom’s only difficulty was having to adjust to have kashrut in her home when my wife and I visited their house. What’s been interesting, as I’ve grown spiritually, is that they have started to admire what I’m doing and support it more. In the Orthodox world I’m seen as a bit of a rebel, but maybe I’m just going back to my roots. I’m more on the same page with my parents than I used to be, even before I became religious.

By now I’ve stopped calling myself Chabad. There are things in that community that I strongly disagree with, but I still think there’s so much truth and value to it. I call myself Modern Orthodox when I’m speaking publicly. I was drawn toward this change because I was bothered by the fact that the wisdom of the world—things like culture, science, math and so on—are not taken into account in the Haredi and ultra-Orthodox world. So I call myself Modern Orthodox today, but in my head I think of myself as half Chabad and half Modern Orthodox. Once you have a family, it becomes easier to practice in some ways because there is a lot of structure in which to be involved in the Jewish world. Going to shul on the High Holidays and having Shabbat every week with your family is very invigorating and special. It’s funny because that aspect of Jewish practice is not that different from other sects of the community, and I think it’s a big part of what ties us together.

Elad Nehorai, 30, Founded Hevria, a creative Jewish community, and is a leader of Torah Trumps Hate, a progressive Orthodox group.

______________________________________________________________________

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]Mikhl Yashinsky, 30[/custom_font]

Credit: Sam Sonenshine

My parents were raised pretty differently. My father came from an Orthodox home, where they kept Shabbos, kashrus and mitzvahs. My mother grew up in the same neighborhood, a suburb of Detroit called Oak Park, but she was raised in a very different environment. It was very Jewish—her parents spoke Yiddish—the difference was that both of her parents were artists and actors, so their Judaism was different from the connection my father’s family had to their religion. Our level of observance landed somewhere between their backgrounds.

I have three older brothers, and there was always a focus on raising us Jewish. We weren’t Orthodox but would often have Shabbos dinner together. We wouldn’t keep all of the prohibitions of Shabbos. We did fast on Yom Kippur and keep the dietary rules of Pesach, but we never had a feeling that we must do things a certain way. Only my middle brother and I went to Jewish day school, and I think that’s one of the ways my identity was shaped by the forces of history. Going to day school, I was required to learn Hebrew and understand Jewish texts. The learning and literacy that I gained there added to my own experience and to my Jewish life as a whole.

When I really started to study Yiddish, it felt very natural, like it was within me, and that I just had to train my lips around the contours of the words. When you learn Yiddish, it’s not just a language. You learn what it means to be a Yid, a Jew. For me, being Jewish means reading and speaking Hebrew and Yiddish, feeling connected to the land of Israel, observing the holidays with friends and family, and feeling at home at shul. It’s also a state of being, a state of connectedness to your peoplehood, which means ritual and culture. That doesn’t mean I keep all of the mitzvahs in the book, but I’m happy that I have that knowledge, and I could go back and study more if I wanted.

All of the ruptures of the 20th century, the tragedies and destruction, created a major break in the way Jews relate to their history. But these events also brought a kind of rebirth. It’s one thing that was lacking in my Jewish education. You study biblical and rabbinical texts, and then you jump forward to the Holocaust and the State of Israel, and now you’re here. There are all of these years of civilization in between that we weren’t exposed to, all of these rich cultures and texts, and I think that was a major fault. I don’t think the name of the writer Shalom Aleichem was uttered once in my school. But a lot of people of my generation are trying to go back and learn what we didn’t learn, and I think it connects us more deeply to our national history.

Mikhl Yashinsky, 30, is a theater director, playwright, actor and Yiddishist. He is currently performing in the Yiddish production of Fiddler on the Roof in New York.

______________________________________________________________________

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]David Yarus, 32[/custom_font]

I’ve been on a Jewish identity rollercoaster. My parents were Reform until I was about six. In kindergarten they sent me to Jewish school, so we also made the house kosher so we could have people over. In that transition, my parents became kosher and started keeping Shabbat. In Miami, Jewish identity was based on how observant you were. Almost everyone in our neighborhood was Jewish, and it was more of a question of “what do you keep?”

Then I went to St. Albans in Wash-ington, DC, after applying on a whim without telling my parents. I was the most affiliated and engaged Jew in the school. So my experience shifted from where my identity was based on practice, to being the “billboard Jew”—whatever I was doing was seen as “this is what Jews do.” It was a crazy amount of responsibility. But it also helped my understanding of being a global citizen and seeing my Jewish identity in the broader context of the world. In college, I did my own thing and was not really practicing. Later on, I started getting into Jewish mysticism and re-engaging with my identity. When I moved to New York in 2010, I started keeping Shabbat and kosher again.

During my professional and philanthropic experiences I became turned off to the Jewish experience. But two years ago at Burning Man, I had Shabbat with a thousand people from all over the world, and it was the most beautiful Shabbat I’ve ever had. From there, I began questioning and reframing my Jewish identity and experience. I’m more excited about my practice now. I don’t do anything just because that’s how it’s done. Practicing without the kavana (intention) or understanding of why, that would lack integrity for me. Once I leaned into designing the tradition I really wanted, it ignited a new wave of excitement in my practice. What does that look like? Instead of going to synagogue and sitting through three hours of prayers I don’t understand, it means designing meditation and sound work around that holiday that allow me to get the most out of that holiday experience.

All of the institutions and organizations that are running the Jewish world were built and run by our parents’ and grandparents’ generation who practiced and lived Judaism differently. Before, there were details and divisions that put people in boxes. But for me Judaism is more fluid, inclusive and integrated. Those are all key generational values that are important to the millennial experience. Human values like inclusivity, equality, women’s empowerment are part of our foundational belief system. Where elements of Judaism might rub up against those, my human beliefs and experiences are the first lens that I’m living through. And then, it’s about reconciling those beliefs with Jewish values and experience.

A friend told me that 70 percent of non-Orthodox marriages were interfaith, so next generation, everyone is bringing a “plus one” to the table. The reality is that it’s happening, so now the question is how do we engage the plus one so everyone is inspired to come back. If we don’t, we alienate and lose everyone. The future of the Jewish people is going to look more black, brown, blue and LGBT than it does today. We could either ignore that, or engage that conversation in meaningful ways.

David Yarus, 32, is the founder of JSwipe and Mllnnl, a digital marketing agency that helps brands connect with millennial audiences.

______________________________________________________________________

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’] Asya Vaisman Schulman, 35[/custom_font]

My parents are from Chernivtsi, Ukraine, and I was born there. We lived in Moscow until I was seven, at which point we moved to North Carolina. Growing up, we weren’t super traditionally observant, but Jewish identity was very, very important in my family. My father was very invested in Yiddish language and culture. He himself did not speak fluently, but three of my four grandparents do. I grew up with this sense that Yiddish is a really important part of our identity, and in the history of the Jewish people. I grew up listening to Yiddish songs and klezmer music and the Yiddish phrases that everybody hears.

In high school, I started studying the language with private lessons, and then continued on through college and grad school. It made sense for me to choose Yiddish: I’ve always loved languages, and I think my parents successfully transmitted to me their idea that Yiddish is a language that was spoken by every single one of my ancestors for a thousand years—and I could contribute to maintaining it.

I always wanted to at least teach Yiddish to any kids I would have. Luckily, I married someone who also values Yiddish very much. In fact, we met at a Yiddish weekend, a Shabbaton for young people who speak Yiddish. Now my husband is the main person transmitting Yiddish to our daughter, who is six and a half. He speaks exclusively Yiddish to her.

I see this as a toolbox for her. It is one of the options available to her in expressing her Jewishness, and I hope she will enjoy everything that Yiddish and Yiddish culture has to offer. She will have the option of going on and reading all of Yiddish literature, if that is something that she wants to do, or speaking to other Yiddish speakers. There are so many wonderful songs, and great literature—so much that can be discovered if you have access to the language. The connection to her past is also important, the same way it was for me: Yiddish’s thousand-year history as the language of Ashkenazi Jews in Europe, and later in Eastern Europe. In Yiddish there’s this term, di goldene keyt, “the golden chain,” which symbolizes transmission across generations. Yiddish is one of the things that help connect my daughter and me to this di goldene keyt of our ancestors.

Asya Vaisman Schulman, 35, is the director of the Yiddish Language Institute at the Yiddish Book Center.

______________________________________________________________________

[custom_font font_family=’raleway’ font_size=’40’ line_height=’26’ font_style=’none’ text_align=’left’ font_weight=’800′ color=” background_color=” text_decoration=’none’ text_shadow=’no’ padding=’0px’ margin=’0px’]Seth Mandel, 37[/custom_font]

I was born in Lakewood, New Jersey, which is home to one of the largest yeshivas in the world. Even though my religious observance never quite went to that level, I benefited from having that around. My parents didn’t grow up in an Orthodox household, but we got progressively more religious as I was growing up, and by the time of my bar mitzvah we were basically Orthodox. It was really gradual and I was so young, so I’m not really sure what the reason was behind that. What stands out to me about my Jewish life is the fact that my parents let us go at our own pace. They certainly led the way and had a way they believed was preferable. But we had the space to grow into our own, so where I ended up is really where I wanted to be. I’m not one of those people wondering if the grass is greener on the other side. It was a process that took place all the way throughout college. I was mostly keeping kosher by then, but I still did eat out, mostly vegetarian food to avoid that conflict. After that, I became shomer shabbos and shomer kashrut. I went through a period where I was even more religious. I mostly stopped listening to secular music, which was a lot for me because I’m a big music fan, and that was too much for me.

Now we consider ourselves Modern Orthodox, and I think the whole family is on the same level of religiosity. As far as practice goes, if you make time, you find time. I have kids now, and that makes a difference. You really feel the weight of history, that responsibility to carry on a tradition that’s thousands of years old, and you see the beauty in it. I daven every day and take time to learn by myself. I make it a practice to study shulchan aruch and say tehillim on my commute. We make kiddush and motzi at home. My kids will see me davening and know that kiddush is coming. The actuality of practice, the physical traditions and rituals are what make a big difference when you’re a parent. You have to know enough to answer questions, to help them learn. You also see it through a child’s eyes, which is rare because it’s tough to remember what it’s like learning about these things as a kid. When you have a family and you’re resolved to live a religious life, not even strictly observant, you tend to see its values everywhere. The kids want to know where they’re from, what they can and can’t or shouldn’t do, and all that’s informed by Judaism.

Seth Mandel, 37, is the former op-ed editor for the New York Post and executive editor of The Washington Examiner.