In 1964, the Jews of Hattiesburg, Mississippi, and other southern towns didn’t always welcome their northern cousins or join the front lines of the civil rights movement…

By Marc Fisher

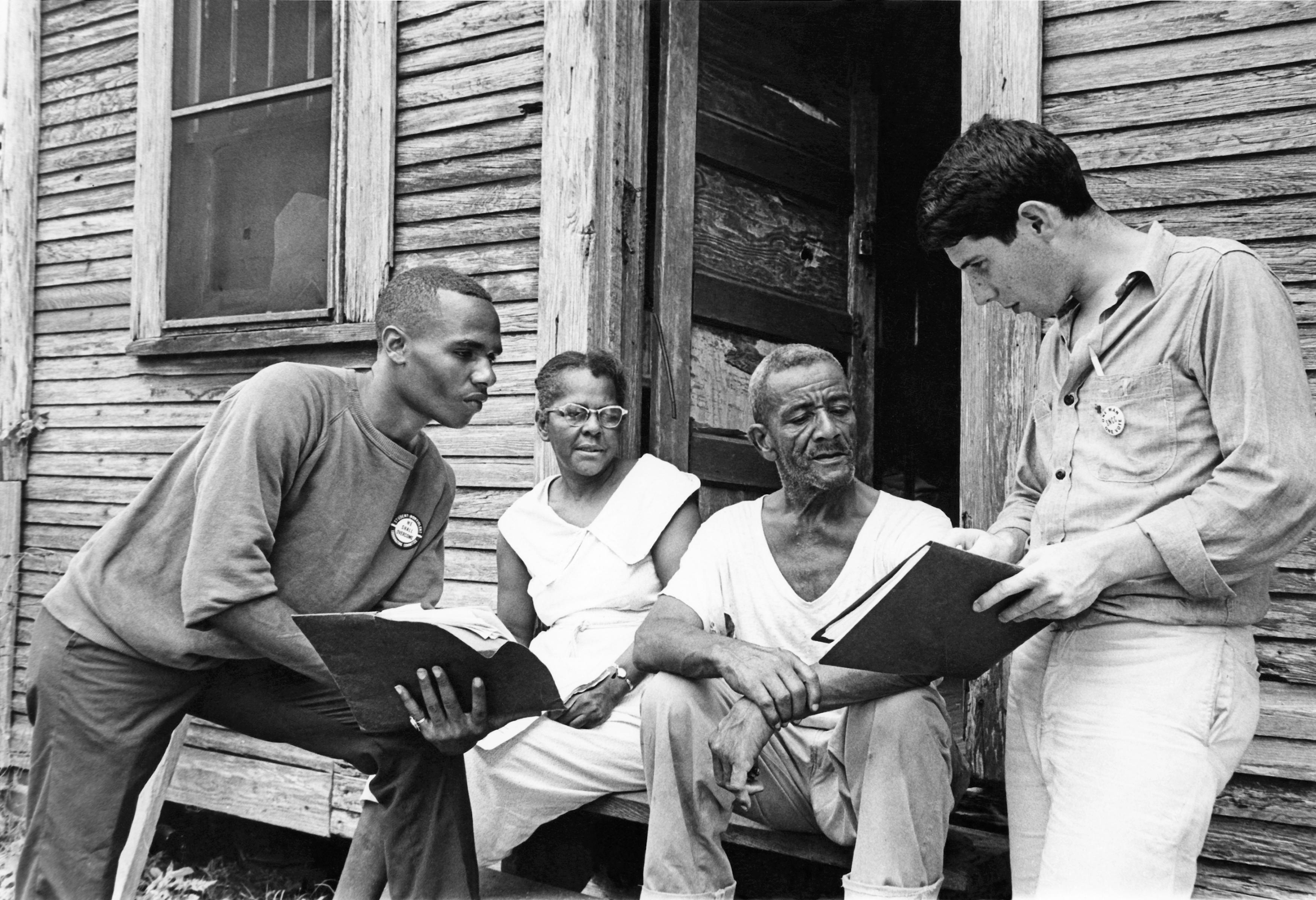

Rabbi Arthur Lelyveld, fresh off the bus from Ohio, was going door to door in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, trying to register black voters. This was Freedom Summer, July 1964, and Lelyveld had been telling his congregation back in Cleveland that Jews had a special obligation, one stemming from Leviticus: “You shall love him as yourself, for you were strangers in the land of Egypt.”

Now he was walking along the streets of Hattiesburg with two white men and two black women, young volunteers in the battalion of civil rights workers—about half of the 1,000 visitors from the North that summer were Jewish college students—who had come to Mississippi to deploy the ballot box and the schoolroom as weapons against segregation. The sight of young men and women of different races walking together was enough to stir several white men to shout at Lelyveld and the others: “Nigger lover!” “White nigger!”

A pickup truck pulled up to the volunteers. Two white men got out. One charged Lelyveld with a tire iron in hand, hitting him twice on the head; the other man then kicked and pummeled him.

In the hospital the next day, a small group representing Hattiesburg’s Jewish community visited Lelyveld and urged him to get out of town. “We had a group that asked him to leave,” says Maury Gurwitch, then the owner of The Smart Shoe Store in downtown Hattiesburg and president of Temple B’nai Israel. “We said, Rabbi, we have enough tsuris being Jews here. You’re going to get us burned out or killed. These do-gooders were here 48 hours and they were gone, but we had to stay. We said we’d buy him a ticket, just go, and he said, ‘Don’t worry, I can’t wait to leave.’” Lelyveld, who lost a lot of blood but escaped without a fracture, was escorted out of town by U.S. marshals. He had spent but five days in Mississippi.

Gurwitch, 84, still lives in Hattiesburg, where he and his wife Shirley are one of about 20 remaining Jewish families. Their full-time rabbi, very likely the last one their shul will ever have, just left town in June. But Hattiesburg is home, as it was in 1964, when the Jews, many of them merchants whose downtown shops depended on both white and black patronage, did their best to navigate a frightening time.

Hattiesburg, then a town of about 30,000 people, was one of the epicenters of Freedom Summer—the ambitious, audacious drive to register black voters, teach black children about their history and their rights in makeshift Freedom Schools, and punch some holes in the southern regime of segregation. Although years of boycotts and legal efforts had won a technical integration of the nation’s schools, daily life in the South had not changed dramatically.

Hattiesburg was selected as a focal point of the campaign because it “has had a long, tough history of civil rights activity, primarily centered on the denial of the right to vote,” according to a treatise published by Freedom Summer organizers that year. The county clerk had refused to obey a federal court’s order that he register black voters. Local authorities had arrested northern clergymen, including rabbis from the Rabbinical Assembly of America, who had joined local black activists in a week-long demonstration that January protesting the refusal to register black voters.

“Look, we hated it, them coming from the North to meddle in our business,” says Marvin Shemper, 70, whose family owned a scrap yard in Hattiesburg for decades. “Things were already changing here. But it was dangerous. When these volunteers left town, we had to deal with what happened.”

What happened was threatening letters left on the synagogue’s lawn, phone calls from gentile friends warning against cooperation with the civil rights workers and visits to their shops from black preachers demanding that blacks be hired as sales clerks. The owner of the local TV station, Marvin Reuben, aired editorials denouncing the Ku Klux Klan, which retaliated by shooting at his broadcast tower and pouring sugar into his wife’s gas tank.

There were boycotts from both directions: by whites who said they wouldn’t shop in stores that hired blacks, and by blacks who insisted that they be hired at places where they spent their money. Gurwitch told the black protesters that he had only three clerks and couldn’t afford to hire another, white or black. Next door, at Milton Waldoff’s department store, the owner sought to get out ahead of the protests, hiring several black sales clerks, making a couple of them managers, and rewriting the cards in the shop’s charge account files to add “Mr.” and “Mrs.” to black customers’ names.

As the boycott continued, some black customers called Gurwitch and told him they needed shoes, so he brought a selection home. Nurses and waitresses who needed footwear came by at night so they could respect the boycott and still be equipped for work. “I couldn’t be seen to stick my neck out, or my business would be destroyed,” Gurwitch says. “But of course the blacks were right—it was so tough on them for all those years. We felt sorry for them, being pushed around like that.”

After a few weeks of the boycott, Gurwitch hired his babysitter’s brother, a black man who was later drafted and killed in Vietnam, and his customers returned (although he says many black clients still asked to be served by a white clerk).

Change came to Hattiesburg, but to Gurwitch’s mind, the northerners who visited that summer were not the cause. “The rabbis and the Jewish students didn’t do it,” he says. “A different group of them came to town every week. They stayed with the black people. They never came to temple, never came in the store. It was the black people stepping up and marching that did it. They did it themselves.”

Barney Frank was a graduate student at Harvard when he joined a group of students to spend five weeks in Mississippi, mainly organizing black Democrats in Jackson. Frank, who later served in Congress for 32 years, says it was no secret that the northern volunteers were mostly Jews. “I was quite aware of it and proud of it,” he says. But in all his time there, he recalls only a single encounter with southern Jews, a dinner at a Jackson restaurant with the family of a student at Wellesley College whom he’d met in Boston.

The dinner went well enough, but the aftermath stopped him cold. The family let Frank know that they had received 90 phone calls from friends and neighbors asking why they were hanging around with those outside agitators.

From that point on, Frank made a point of avoiding Jackson’s Jewish community—not that he’d intended to spend much time with them, since “we were focused on the situation of the black people. Just their having dinner with me was an act of bravery, and I appreciated it. I knew they faced ruin and maybe violence if they were seen with people like me.”

“Massive resistance” to integration is a phrase that peppers history texts about the civil rights era, but those two words do little to capture the tension and overt violence that met the volunteers who arrived in Mississippi by bus in the summer of 1964. More than 30 churches were burned or bombed, volunteers were jailed and beaten, clergymen were attacked.

The visitors were portrayed in the local press as agitators, communists or worse. “If you were a white person of any substance or position, you did not want to be seen as supporting outside agitation,” says Stuart Rockoff, executive director of the Mississippi Humanities Council and former historian at the Goldring/Woldenberg Institute for Southern Jewish Life in Jackson. “Even the Jewish liberals believed in gradual change. Any sort of aid to the volunteers was done quietly, certainly in Mississippi, where massive resistance was in full flower.” He adds that southern Jewish opposition to the northerners’ civil rights pilgrimages reached its peak in the summer of 1964.

Studies of the Jewish northerners who traveled south for Freedom Summer—and there have been a slew of them—conclude that the young people who rode the buses to Mississippi and other southern states that year were driven by a sense of moral outrage over segregation; a desire to escape boring jobs, difficult families or the prospect of settling down in suburbia; and the excitement of making friendships or finding romance across racial lines—what historian Debra Schultz called “the intoxication of the freedom high.”

Far less attention has been focused on Jewish southerners, many of whom found themselves caught between their moral affinity with the civil rights volunteers and the fears and anxieties that came with being outsiders in overwhelmingly Christian white communities. Cheryl Greenberg, a historian at Trinity College who has studied southern Jewish communities during the civil rights era, says there are two schools of thought about those small clusters of Jews who survived and even thrived in towns where the Klan hated blacks most of all but targeted Jews, too:

“One school says that southern Jews were more racially progressive than southern whites, but were not willing to get involved because they felt vulnerable, thinking of events like the [1915] lynching of Leo Frank.” Indeed, Jews in towns that volunteers visited in 1964 did face consequences—temple bombings in Meridian, Mississippi, and Atlanta, Georgia; boycotts in quite a few communities; and personal threats to rabbis, lay leaders and local merchants.

Freedom summer volunteers singing “We Shall Overcome,” the anthem of the Civil Rights Movement on June 19, 1964.

But the other view of southern Jewish communities is less forgiving, and this is the one Greenberg subscribes to: “Saying you were scared is not an excuse,” she says. “They could have been more public. The religious education I had emphasized the Jewish ethical imperative. So I feel the reason to be Jewish is the moral obligation to do the right thing and not give in to fear. I don’t know that I would have done anything, but I hope I would have.”

Aaron Henry, director of Mississippi’s NAACP chapter, expressed that view in 1964, writing that, “The image of the Jew in national civil rights activity has not rubbed off on the Jewish population of Mississippi. There is little difference, if any, between the Gentile White and the Jew in their treatment of the Negro.” Some black leaders said they expected more of Jews, both because of the biblical directive for Jews to repair the world and because Jews shared with blacks a vulnerability that made it incumbent upon them to stand together against oppression.

Southern Jews who were active in national Jewish organizations urged leaders of the Anti-Defamation League, the American Jewish Congress and other groups not to support Freedom Summer and similar ventures. “Do not come” was their message, Greenberg says. “You’re endangering us.”

Few southern Jews were avowed segregationists, although some did join the White Citizens’ Councils or otherwise helped white Christians defend the status quo. In South Carolina, the speaker of the state House, Solomon Blatt, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants, fought against the integration of schools and colleges. As the historian Clive Webb documents in Fight Against Fear: Southern Jews and Black Civil Rights, Charles Bloch, a Jewish state legislator in Georgia, was an avid supporter of the White Citizens’ Council, wrote a book on states’ rights and went to court to try to block the use of state funds in integrated schools (his case didn’t go anywhere). In Jackson, the Clarion-Ledger praised the city’s Jewish community for standing with white Christians as “patriots” in support of states’ rights.

And relatively few southern Jews decided to jeopardize their safety and status by linking arms with black marchers or embracing the influx of northern civil rights workers. “There was no civil rights activism among Jews in Mississippi,” says David Orlansky, 83, a retired federal judge who grew up in the Delta and lived in Greenville for much of his life. “I don’t know of a single Jew who was out front in the movement.”

That doesn’t mean southern Jews opposed civil rights. They were balancing competing concerns. “Somehow the civil rights activists got it in their heads that the Jewish merchants had way more control over the political sphere than they really did,” Orlansky says. “So they made all these demands on the merchants—use courtesy titles for blacks, employ more blacks—and when their demands weren’t met, they started boycotts. And so here were all these Jews who were sympathetic to the movement, saying, ‘Damn, I’m the best friend you’ve got in town, and you’re boycotting my business!’”

Mark Bauman, a historian and editor of Quiet Voices: Southern Rabbis and Civil Rights, 1880s to 1990s, says some modern historians are “too hard on southern Jews.” He says a number of affluent southern Jewish women played especially prominent roles in that interracial coalition by taking out newspaper ads urging whites to stay in newly integrated schools, and some southern rabbis did take risks to stand publicly with blacks seeking voting rights and access to public schools, either from the pulpit or at meetings of national organizations. “Their congregations tended to try to silence them, demanding that the rabbis clear their sermons with the board, but most rabbis refused and insisted on an open pulpit,” he says.

Within those congregations, however, the prevailing sentiment was that it behooved Jews to support the movement quietly, if at all, and that view was entirely understandable, Bauman says. “There was real reason for their fear,” he says. A temple in Atlanta had been bombed in 1958. The Mississippi Sovereignty Commission kept an investigative file on B’nai B’rith (agents reported observing no subversive activity at the Jewish group’s meetings, but noted that every morning, members would gather in groups of about ten men for unknown purposes). Rabbis’ homes were attacked in several cities. Congregational leaders regularly got ugly, threatening calls at home.

“Jews in the South were marginal,” Bauman says. “They’d worked hard to get into the community Rotaries and ministerial associations and country clubs. They knew how to work behind the scenes and that’s what they preferred to do. Then they see these northern rabbis coming in for a week and going home to be a hero to their congregations. Most of those northerners don’t even contact the local Jewish community, and if they do, and the southern Jews say, ‘Please don’t do this,’ they’re ignored or called racists.”

In retrospect, Bauman acknowledges that without marches, voter drives and other civil rights work, mainly organized by northerners with a disproportionate representation of Jews, Congress would not have moved ahead with civil rights laws and change would not have occurred as quickly as it did.

“But that’s all hindsight,” he says. “If you’re a Jew in Hattiesburg in 1964, do you want marches and demonstrations? They were separated socially. These Jews were living through terror.”

Jews started settling in Hattiesburg in the first years of the last century, opening dry goods and department shops on the main street. They’d arrived from New York and Baltimore, or directly from the old country, lured by word that there was work to be had in the South. By 1915, there were enough Jews to establish a synagogue, and when the Army opened a base just south of town a couple of years later, Jewish soldiers from the North learned that they could spend holidays with the Jews of Hattiesburg.

In 1964, Hattiesburg was home to about 180 Jews. That number has declined sharply in the decades since, as most children of the 1960s and 1970s moved away after college. Those who remain recall Freedom Summer as a time of fear and uncertainty. They retain a visceral resentment of “meddlers” from the North, even as they readily acknowledge that the movement accelerated the pace of change. But the wounds of 1964 are deep enough that all of the Jews I spoke to in Hattiesburg have put out of their minds a chapter in which their own rabbi confronted them with their silence.

Hattiesburg Rabbi charles Mantinband and students.

Temple B’nai Israel had had tough, liberal rabbis before. In the early 1960s, Charles Mantinband had become a prominent advocate of civil rights, speaking to national Jewish groups, arguing that “the American Negro is the only real American… the only American unwilling to make the slightest compromise with the American creed.” Mantinband openly chastised southern Jews for looking the other way: “It is their foolish belief that as long as the Negro remains the scapegoat and the victim, the Jew is relatively safe,” he said in a speech in New York in 1962 titled “In Dixieland I Take My Stand.”

“Despite fear of reprisal,” Mantinband wrote, local Jewish leaders needed to step forward and fight with blacks against white oppression. But Mantinband did not go as far as Perry Nussbaum, the rabbi at Beth Israel Congregation in Jackson, who held Mississippi’s first interracial service and drove 150 miles each week to the state prison in Parchment where Freedom Riders were being held, to deliver supplies and exchange messages with relatives up North.

Nussbaum’s highly public acts on behalf of civil rights volunteers were not popular among his fellow southern rabbis. Even Mantinband said he preferred to work within Jewish circles rather than make a bright public show of support for black demonstrators.

Moses Landau, the rabbi in Cleveland, Mississippi, at the time, said Nussbaum was exposing southern Jews to too much risk: “Hundreds of our families live isolated, two or three in a community, in an emotionally charged atmosphere,” he wrote to Nussbaum. “It is your privilege to be a martyr. There are dozens of vacant pulpits. You can pick yourself up within 24 hours and leave. Can you say the same of the about 1,000 Jewish families in the state?”

Nussbaum did pay a price—his home and his synagogue in Jackson were firebombed. In Hattiesburg, Mantinband’s mail was opened, his house surveilled. Meanwhile, Mantinband’s congregants debated what to do about their rabbi. “Our rabbi was leading the parade, so to speak, when the Klan was very active here,” Gurwitch says. “I kept saying to him, ‘Rabbi, my customers are coming to me saying, You better control your rabbi—he’s going down to the colored and making trouble. We just wish you’d be careful.’”

Mantinband later wrote that he felt pressured to leave and resigned. Gurwitch and others in Hattiesburg say that’s not what happened; the rabbi’s eyesight was failing and he moved to Texas to be with relatives, unrelated to his civil rights advocacy.

Mantinband’s successor, David Ben-Ami, was 13 when his family fled Germany to escape the rising tide of Nazism. He lived and studied in New York, becoming a rabbi and serving several temples around the country before arriving in Hattiesburg in 1963. Ben-Ami jumped right into the fray: He raised money to rebuild burned black churches. He joined black celebrity activists Dick Gregory and Sammy Davis, Jr. in a drive to distribute 20,000 Christmas turkeys to poor families, black and white—a move that white groups denounced as meddling. And Ben-Ami was the only local clergyman who visited nine northern Presbyterian ministers who’d been jailed for civil rights activities in town.

“The sheriff didn’t take too kindly to the rabbi’s visits, and reported them back to leaders of the B’nai Israel Congregation, who in turn called on their spiritual leader,” Washington columnist Drew Pearson wrote in a piece that appeared in more than 1,000 newspapers across the nation. The interracial turkey distribution was the last straw, Pearson reported: “This time, the leaders were insistent that Rabbi Ben-Ami should leave…They pointed out that they had heavy investments in Hattiesburg which could be bankrupted by boycotts.”

Ben-Ami’s contract was not renewed.

Today, the name Ben-Ami rings no bells with Jews in Hattiesburg. “Shirley and I can remember almost nothing about him,” Gurwitch says. If he worked with civil rights groups, “we know nothing about it and it did not affect our temple. Obviously he made very little impression on our congregation and caused no problems.” Three other prominent members of the Hattiesburg Jewish community also said they recalled little or nothing about the rabbi who left after one year.

When the Freedom Summer kids first arrived, Alex Loeb was sympathetic but skeptical. The owner of the biggest store in Meridian, then Mississippi’s second largest city, Loeb was a worldly fellow, a former journalist, a painter as well as a merchant. He was married to a former New York Times editor, and they traveled often to Manhattan.

Loeb, at 96 now frail but a sharp and witty talker with dancing eyes and a detailed memory, says Meridian’s Jews steered clear of the Freedom Summer activists, but some tried on their own to do right by black neighbors and employees. Unlike many fellow merchants, he was willing to take public positions on matters of race. When the local newspaper proposed to bring Alabama segregationist J.B. Stoner to town, Loeb went to see the publisher and threatened to pull his advertising if the invitation stood. The publisher backed down and ran an editorial saying that Stoner was not welcome in Meridian.

When Loeb hired his first black sales clerk, the Klan called a boycott of the shop and Loeb got bomb threats. But he says he was no hero. Asked to intercede after a civil rights worker was jailed, Loeb refused. “The most I can do for you is cut him down when they put him up,” he recalls saying.

He was dismissive of the whole northern volunteer phenomenon. When 24-year-old Michael Schwerner and his wife Rita arrived in Meridian from New York in their VW Beetle to open a Freedom Summer office and launch a voter registration drive and a community center for black residents, Loeb saw their presence as a matter of misplaced idealism: “They were meddling in things they didn’t know about. I thought the North needed all of that civil rights work just as much as we did.” Loeb and his wife had taken the trouble to send their daughters to integrated schools in Arizona and New Mexico, which was more than many of his friends in New York had done. “We’d go to New York parties and get lectured about what we should be doing in Mississippi,” he says. “But they weren’t doing anything in New York—they were Jewish people and they hardly had any Christian friends. They couldn’t understand that the animosity that existed for the blacks could be turned right after them against the Jews.”

One day that spring, an Episcopal priest came into Loeb’s store with a scruffy white guy sporting a beatnik-style goatee. Other merchants were refusing to cash Mickey Schwerner’s checks—would Loeb help? Sure, he said—and he offered the kid some advice: If you’re going into the homes of black people, put on some nicer clothes. Jeans and T-shirts would not cut it with black Meridians. Schwerner stuck with his jeans, but the two men developed a cautious friendship, arguing each Saturday about the town and politics.

Loeb had told his cashier to accept Schwerner’s checks, but the New Yorker insisted each week on having the owner do the honors. “He was very savvy—he wanted people to see me helping him out,” Loeb says.

Schwerner’s tactic had the desired effect. Loeb became known as someone who would help out. His wife, a Swarthmore College alumna, would get phone calls from parents of Swarthmore students who were part of Freedom Summer; she would duly check on their kids and report home.

Even those small courtesies got the Loebs in trouble. They got calls at home from whites accusing them of being members of the NAACP. Segregationists told Loeb he needed to fire a black employee who had been seen teaching at the Freedom School; Loeb refused.

Eight months later, Schwerner, Andrew Goodman and James Chaney disappeared and were murdered by Klansmen, a crime that put a national spotlight on the Freedom Summer campaign. President Lyndon Johnson put 200 FBI agents and 400 Navy personnel on the hunt for the civil rights workers after they vanished.

When the young men’s bodies were found buried in an earthen dam in rural Neshboa County after a six-week search, the misgivings that many Jews in Mississippi had about the civil rights campaign turned into palpable fear.

Fifty years after Freedom Summer generated the political oomph to get the Civil Rights Act signed and the Voting Rights Act passed, downtown Hattiesburg is not what it was. Despite various efforts at revival, the midday scene is one of barren sidewalks and too many empty storefronts. When I walk into a downtown restaurant with three Jewish businessmen in their 70s and 80s, we run into the mayor, Johnny DuPree. DuPree—who is black and spent 15 years as a salesman at Sears before he went back to school, got his degree and launched a second career in politics—has been mayor since 2001. He turns to some of the city’s Jewish elders for counsel from time to time, but Hattiesburg—like most Mississippi cities—is majority-black now, its elected officials evenly divided between blacks and whites.

Dupree calls the trio “the pillars of the city.” But the Jewish merchants who once played a vital role in the city have little presence downtown anymore. There’s only one Jewish-owned shop left downtown, the Sacks Outdoors footwear and apparel store. Gurwitch is retired, his shoe store having moved out to the mall decades ago. Waldoff’s downtown clothing store is long gone; he’s now a consultant to retailers across the country. And Shemper’s family sold the scrap yard that their father founded, although Marvin Shemper remains active in Hattiesburg real estate.

At the lovely brick temple on Mamie Street, the rabbi’s study is vacant. Gurwitch comes in once in a while to check for messages on the answering machine. At Friday night services, a few locals are joined by a handful of students from the University of Southern Mississippi and a couple of doctors from the local hospital. There’s still a Sunday school, with 13 children enrolled. “I don’t see it lasting,” Gurwitch says. The new rabbi, yet to start work, is a student from Ohio who will fly in every other week, just for the weekend. They hope to keep their shul open for as long as they can, but they sense that they are the last Jews of Hattiesburg. Gurwitch says he can see perhaps moving to Houston to be near his children.

They are proud to be southern Jews. They feel accepted. Yet there is always that sense of being the outsider. I notice that the Jewish cemetery has no sign, no iron gate—just a chain-link fence. “We didn’t want to call that kind of attention to it,” Marvin Shemper says, “’cause you never know what might happen.”

What a fine and sensitively drawn article. It really shows the dilemma of being a Southern Jew during the civil rights period in Mississippi. I really think this article wants to be a book, and I hope it gets its wish.

I found this tp be a very fine article. It’s large amount of trenchant detail about the daily lives and feelings of southern Jews during the civil rights protest period is something I have never read before. As another commenter here says, This could be the basis for a good book.

i just attended the 50th anniversary of Mississippi Freedom Summer: 1964-2014 as a witness to the events commemorating the “Mississippi Freedom Summers” of the past. Many of those attending were the “veterans” who came from the North. Most were students, and according to Julian Bond, 60% were Jews. I went because I am making a film about Heather Booth, who was one of those students. It was an emotional 5 days. I commend you on your article about the southern Jews who were there, most of whom did not welcome the Jewish students from the North. I commend you for presenting their dilemma. As Jews we believe we must follow the path of justice, but we see that many of our co-religionists have other concerns and interests. It is important to hear their positions, as it is just as important to present the other side, and to become activists in the struggle for justice.

Thank you MOMENT Magazine for continuing the high standards set by Leibel Fine.

To the Editor:

As a congregant and current Treasurer of Congregation B’nai Israel, this article is wreckless and harmful and needs to be taken down immediately. In talking to 3 or 4 of our senior congregants some very poor, misinformed conclusions are formed not to mention facts are mis-stated (our cemetery does have a sign and a beautiful wrought-iron gate; our Board voted not to renew our previous rabbi’s contract and our Board decided to employ a student rabbi short-term but eventually return to a full-time rabbi in the future; there is no doubt that Mayor Dupree may have referred to Marvin, Maury & Milton as “pillars of the community” but I am positive he did not call them “the pillars of the community”; and others). Hell, Marvin Shemper’s last name is misspelled throughout the article….I know, he’s my uncle!

I would welcome a call from the editor of MOMENT to discuss these matters important to our congregation…..a congregation like any other (Jewish, Christian or other), struggling to keep those Jews remaining in the community today involved.

Thank you.

Sincerely,

David Shemper

Treasurer

Congregation B’nai Israel

Hi David,

Will you please send a letter to the editor via editor@momentmag.com?

I enjoyed your article. My conclusion: th northern jews were brave . That was a difficult thing to do. But it was easy for us northerners to demand that other people be brave. We did not stop to think that they would have to pay for our bravery.

Fascinating article that I too hope will be turned into a book on southern Jews and the Civil Rights movement. I would recommend that the author explore Savannah GA to compare and contrast the Jewish response to civil rights movement. Savannah has one of the oldest Jewish congregations in the nation and would be a fitting city to examine. In any event, enjoyed the article and responses – well done.