The first slur I noticed was in an October 9, 1962, letter Sylvia Plath wrote to her mother about a separation agreement that was in the works with her husband, Ted Hughes: “I pray he will sign the maintenance before they get him to Jew us…The Yorkshire-Jew miserliness will try to screw me yet.” On October 12, she repeated to her mother that she had to be careful about the “Yorkshire-Jew quality” of his family, who she thought would say she didn’t deserve a penny “as I have the house.” On October 16, with a fever over 101 degrees, suffering chills and in a rage, she wrote to her mother: “Write nothing to any of the Hughes. I stupidly told Edith [Ted’s mother] in a letter this morning that Ted had finally deserted & you would appreciate a word that they care for me & the babies, although Ted does not. This noon I got, from Hilda [Ted’s aunt] the ‘Family position’. The materialist, appalling Yorkshire-Jew skinflint [Ted’s Uncle Walter]: Forget Ted, count myself lucky to have a house, car, two babies & the ability to earn my whole living at home instead of having to go out & work for a boss!” In a second letter the same day, Plath characterized the Hughes family as “inhuman Jewy working-class bastards.”

Uncle Walter, a wealthy man, was not Jewish, and Plath knew it. Her earlier letters expressed regret that he had not done more to help her husband. Hilda’s letter to Plath does not seem to have survived. The Hughes family admired Plath and were upset when Ted left her for another woman, Assia Wevill—who was, by the way, Jewish, and was shunned by the Hughes family, not, it seems, because of her religion but because she had contributed to the breakup of the Hughes-Plath marriage.

No Plath biographer has ever explained her antisemitic slurs, all of which occur in two volumes of recently published letters, and in diaries and journals, some of which have been published. I began working on Plath in 2011, preparing for a biography that was ultimately published in 2013. Since then I have published several books on Plath, and yet until recently I did not think deeply enough about the attitude toward Jews she expressed in her private life. Her signature poem, “Daddy,” reflects such a profound identification with the Holocaust and the plight of Jews, with her father’s German background providing the horror (“An engine, an engine/Chuffing me off like a Jew./A Jew to Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen./I begin to talk like a Jew./I think I may well be a Jew”), that her occasional and incidental antisemitic remarks had never registered with me. Were they that important considering the brilliant corpus of her work?

Recently, while posting on social media about one of her Yorkshire Jews slurs, I realized I had to confront how it was that Plath should malign Ted Hughes’s family, none of whom were Jewish. What would a social media reader make of an antisemitic diatribe taken out of context? Why did she suddenly resort to such vile and, as it happens, factually mistaken denunciations of the Hughes family? So I examined every reference to Jews in diaries she began keeping at the age of eleven. A pattern emerged, fitfully expressed, but with a through line all the way to nearly the last days of her life.

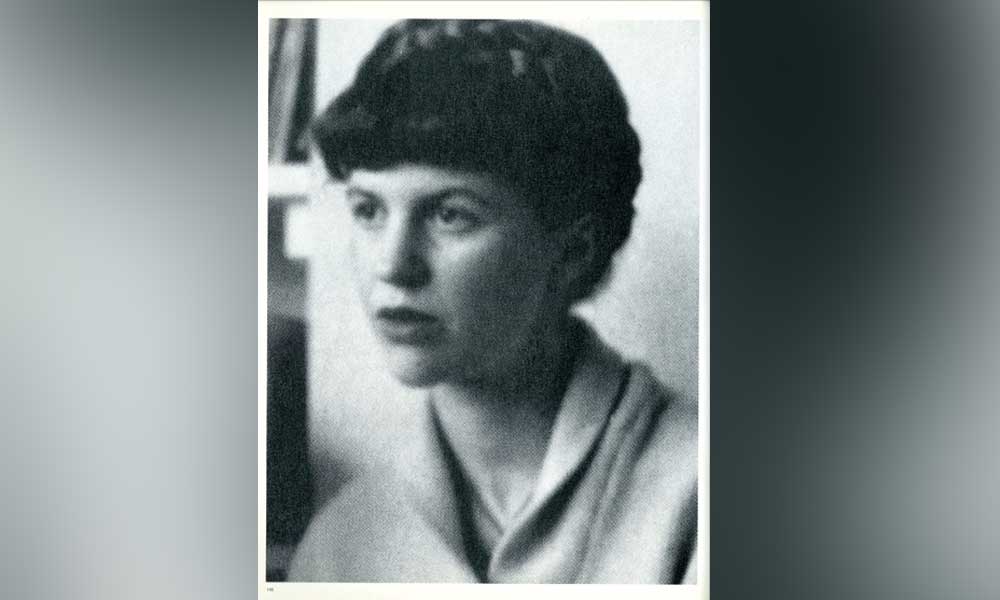

Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath. (Photo credit: Flickr)

Plath’s mother Aurelia, so far as is known, never used antisemitic language, and no one knows what she thought of Jews. A colleague of Plath’s father Otto told biographer Harriet Rosenstein that Otto had “antisemitic tendencies” but did not elaborate. Plath was only eight years old when her father died. What she may have heard from him about Jews is unknown, although “Daddy” portrays the father figure as a Nazi. One of her friends, Philip McCurdy, mentioned that Plath grew up in “antisemitic, WASPy” Wellesley, MA, but he did not comment otherwise on Plath’s own attitude toward Jews.

During Plath’s years in England, beginning in 1955, she would certainly have been exposed to casual slurs about Jews. I heard them during my own trips to England beginning in 1963 (the year Plath died), and was still hearing them while working in London on two books in the early 2000s. Anti-Jewish expressions, coming from intellectuals I interviewed, were commonplace, and no one I encountered in social gatherings seemed to consider that I might be offended by them. After all, I wasn’t Jewish. The same was true in 1979-80 when as a Fulbright scholar I was teaching in Poland, which was rife with antisemitic jokes, some of them targeted at Golda Meir.

Plath’s smears are mild compared to what Hemingway, for example, said about Jews. All the same, why?

Plath’s smears are mild compared to what Hemingway, for example, said about Jews. All the same, why? The question is of interest because of the way Plath used Nazi and Holocaust imagery in some of her most famous poems, including “Lady Lazarus” and “Daddy.” Certain lines in “Daddy,” picturing the speaker on a train to one of the concentration camps and talking “like a Jew” and thinking “I may well be a Jew,” suggest a powerful identification with Jewish people and raise questions about her own experiences with Jews. What did she know about them? How did Jews treat her?

Plath, born in 1932, had German and Austrian grandparents, and during World War II she went to school with immigrants, including German Jews. On January 15, 1944, her diary mentions making a “crazy statue of Hitler in the snow,” but nothing about that suggests admiration of him; he could have been a target for snowballs, after all. Her experiences as a child growing up in the war years are unremarkable: A June 14, 1944, diary entry reports that she went to see Passport to Destiny, an RKO film starring Elsa Lanchester as an English charwoman who, believing herself to be invulnerable (protected by a magic eye amulet) travels to Nazi Germany to personally assassinate Adolf Hitler, but Plath made no comment on the film. She noted listening to homegrown fascist Father Coughlin, who had a radio audience in the millions, but what she made of his antisemitism she did not say.

On January 25, 1946, a neighbor and friend of the Plath family took 13-year-old Sylvia to Temple Israel in Boston: She had heard about Judaism in her Unitarian Sunday school and wanted to learn more. She liked to draw, so it was not that surprising that after the temple visit, she drew a Star of David in her diary and described a pulpit made of solid white marble in between the ark and the Torah. “I had a beautiful time and was impressed,” she wrote in her diary. The next Jewish-related reference is on October 11, 1947, when she recorded her “dread of concentration camp films.”

At Smith College, Plath had a Jewish roommate and dated a few Jewish boys from nearby colleges. Her journal comments at the time were generally free of stereotypes about Jewish friends and acquaintances, but this is not true—to say the least—of comments about Jews she met more casually or observed at a distance. She does routinely note the Jewishness of people she describes (she sometimes mentions the ethnicity of other friends and acquaintances, but not as consistently as with Jews), and the journals have nothing to say about antisemitism at Smith or any of the Seven Sisters schools that had a reputation for it.

Fairly typical was the description of Plath’s first roommate at Smith College, Ann Davidow, “a lovely Jewish girl,” according to Plath, and a “free thinker.” They loved to discuss God, religion and men. If they talked specifically about Jews or Judaism, Plath does not refer to it in letters or her journals. Similarly, at Smith she came under the sway of distinguished critic Alfred Kazin, author of New York Jew, who was impressed with her writing and wrote recommendations on her behalf: She notes that he is Jewish, but no more. On the other hand, this absence of stereotyping does not extend past friends. With Jews seen from a distance, things are very different. In August 1951, Plath was on a Massachusetts beach, taking a break from her babysitting job, writing in her journal and watching “fat, gold-toothed, greasy-haired Jews sunning themselves, and oiling their plump, rutted flesh.” There is no apparent reason for this lapse into bigotry.

In the summer of 1952, she babysat for a Jewish family who had become Christian Scientists, and commented only that she felt “much more at home than I thought I’d be.”

During the summer of 1952, Plath dated a Jewish boy who, she writes, told her about his grammar school in Bridgeport, CT, and how he always came home with a bloody nose until he learned how to fight. In her sophomore year, back at Smith, she mentioned in a letter meeting “really interesting girls,” including a Jewish girl who lived in Greenwich Village. On a visit to New York City in the spring of 1953, she mentions sitting at a table in Delmonico’s for a “stimulating evening” with “very liberal Jews” talking about “racial prejudice and religion.” A Smith classmate, Claiborne Philips, marries a Jewish boy, and Plath tells her mother she wants to visit Claiborne “living now in new york with her jewish [sic] husband” and that Claiborne needs “love and support from her few, but most devoted friends.” Was that because of the Jewish husband? Plath doesn’t say.

In the early and mid-1950s, her interactions with Jews were positive, stimulating and filled with curiosity about their beliefs and behavior (though with no suggestion yet of the later use she would make of them symbolically). Elinor Friedman, a Smith classmate and friend, thought Sylvia had a romantic notion of Jewish identity, finding it richer than the arid, complacent wealthy world of Wellesley, where Plath had grown up. Friedman told Plath biographer Harriet Rosenstein: “I think that the idea of these people who went through great trials and who wandered a great deal and yet had a central core on which they could rely was a big source of fascination. Jews seemed to have a relationship to self that I think she always felt was missing. Whether it was despising herself for her whiteness, the blond hair and white skin and the blue veins—her total waspy self that she was always trying to dissipate, leave somewhere else, by feigning freedom of it in some kind of way.”

Sitting with Ted waiting for a room in the lobby of a French hotel: “Slimy dark curly Jewish Americans saunter down, expensive tweed jackets; “let’s sneak out and not pay.”

Plath had brief love affairs with two Jews. In the fall of 1955, sailing to England for her Fulbright year, she had a shipboard romance with Carl Shakin, an NYU physics major. That he was Jewish did not seem to be an issue for her, and even after they parted, she seemed to retain only positive feelings about him. At Cambridge University she met Mallory Wober, whom she called a “jewish greek god,” powerfully built and an excellent musician. He introduced her to Israeli friends. She seemed entranced with Wober’s family background: “Moorish Jews, Russian Jews, Syrian Jews, etc.” Wober excited her over “goblets of sherry, cracking crimson in the fairytale cheeks of a rugged jewish hercules hewn fresh from the himalayas and darjeeling to be sculpted with blazing finesse by a feminine pygmalion whom he gluts with mangoes and dmitri karamazov fingers blasting beethoven out of acres of piano and striking scarlatti to skeletal crystal.” She made quite a study of him: “his blend of russian, syrian, and spanish jew gives him a subtle strange other-world aura.” She concluded: “I am close to the Jewish belief in many ways.” Wober’s “vital intensity, sensitivity and whole integrity of body & mind” was a relief from the “childish & tea-drinking English men, who idealized one embarrassingly.” He was one of the “giants of the earth,” comparable to an Old Testament prophet. She expected when she met his close-knit family she would enjoy the “vivid warmth and love in their personalities I find very close to home” but would be “really up for examination.”

Apparently, she passed inspection, but the relationship didn’t last—not, by her account, because he was Jewish but because she concluded he was too young to pursue an affair with. They remained friends and she went on to date other men at Cambridge, writing to a Smith College friend about “all the dear, sweet boys (most jewish and negro), but none I could marry.” She doesn’t say why. Though she makes no overtly racist comments about Black people, the interactions she recorded in her journals reflect her view of them as a little exotic. (At any rate, she seemed very little interested in civil rights issues or in the leaders and participants in the civil rights movement.)

Plath was enamored of her Cambridge University philosophy professor, Dorothea Krook, “a blazing brilliant South African jewish woman, incandescent with brilliance and creative and lovely.” In her memoir about Plath, Krook describes a scene in which Plath strikes her as Jewish. But she doesn’t elaborate on what that means; perhaps her comment merely reflects the rapport she felt with Plath.

Throughout this period, Plath continues to note the Jewishness of people she admires or likes, without drawing any explicitly stereotypical conclusions, though they can be inferred. She is upset when the “stupid” family of a friend will not attend the friend’s wedding because the husband is “half-Jewish.” She likes Leonard, the husband of her friend Elinor Friedman, calling him a “handsome Jew, with no vanity, very strong and silent.” Ann Davidow’s husband, Leo, also wins her approval as “a wonder”: “handsome, blond, blue-eyed & Jewish.”

When she doesn’t approve, though, things sound different. Plath didn’t like the couple who had the upstairs flat in the Cambridge house she shared with Hughes, disparaging their “Persian-Jew Scotch-chieftain combination.” She made a comment in her journal about a party with “very dull & wealthy stupid floor decorators & all Jewish businessmen named Goldstone.”

In the next few years—1956-1958–more harshly antisemitic comments appear in her journals—often, as in Massachusetts, about people she spots in public. In August 1956, she’s sitting with Ted waiting for a room in the lobby of a French hotel: “Slimy dark curly Jewish Americans saunter down, expensive tweed jackets; “let’s sneak out and not pay.” On June 17, 1958, she describes a man she meets at a party as “a surprise: no fat oily Jewish intellectual but a thin, wiry, tan fellow with dark, queerly vulnerable brown eyes.”

It’s worth noting that these comments are made in private. When Plath turned to fiction, such antisemitic remarks recede and are replaced with antisemitism as a subject to be explored. On December 31, 1958, she notes a concept for a story: “the awareness of a complicated guilt system whereby Germans in a Jewish and Catholic community are made to feel in a scapegoat fashion, the pain, psychically the Jews are made to feel in Germany by Germans without religion.” But this is a rare instance of dealing with antisemitism directly. In Plath’s fiction of the late 1950s, she did not deal with Jewish characters or make the Holocaust a concern of her work. Even later, in The Bell Jar, in which the horror of the Rosenbergs’ impending execution for treason hangs over the summer of the protagonist’s New York magazine internship and heightens her emotional turmoil, not much is made explicitly of the Rosenbergs’ Jewishness; what’s salient is that they are the scapegoats of a murderous society intent on punishing a couple charged with stealing atomic secrets for the Soviet Union. However, accounts agree that during Plath’s actual month working at Mademoiselle, the experience powerfully depicted in the first part of The Bell Jar, she lectured a Jewish friend, Laurie Totten, declaring that Totten should care about what happened to the Rosenbergs. “She was always asking me about being Jewish,” Totten remembered, adding that Plath told her she felt guilty about the Holocaust and her father’s German background.

Later, after her marriage to Hughes, things sharpen considerably. In an undated journal entry, evidently written around 1960, Jews appear on a train, “coarse—tan-faced.” At a New Year’s 1961 event in North Tawton, where she had just moved with Hughes, she observed “short, dark, Jewy looking Mrs. Young.” On March 2, 1962, Betty Wakeford came “bounding up in a suede jacket with glasses, a long Jewy nose and open grin.” June 7, 1962: Mr. Pollard had an “oddly Jewy head, tan, balding, dark haired.” In an undated journal entry probably written in the summer of 1962, Plath reported that one of the neighbors thought her daughter should be a model. Plath saw a photograph of her, “hard-faced, black hair, a Jewy rapaciousness.”

Plath completed “Daddy,” perhaps her best-known poem, on October 12, 1962, and it reflects a more conflicted, empathetic state of mind than such language would suggest. (“I think I may well be a Jew.”) Her work suggests a powerful propensity to identify with Jews—but also a powerful pull to identify with their persecutors: “Every woman adores a fascist.” “Daddy,” in which the figures of Jew and Nazi evoke the more universal tropes of victim and abuser, was written less than two weeks before she wrote to her mother furiously denouncing the non-Jewish Hughes family as “inhuman Jewy working-class bastards.”

And yet, not long after, she followed up with an October 21 letter to Aurelia, who had apparently urged her toward lighter topics: “Don’t talk to me about the world needing cheerful stuff! What the person out of Belsen—physical or psychological—wants is nobody saying the birdies still go tweet-tweet, but the full knowledge that somebody else has been there and knows the worst, just what it is.” Plath used the Holocaust as a metaphor, but she understood its significance as a crisis for everyone, which is why her mother’s urging her to write about more cheerful topics annoyed her. Separately, she had a profound sense of how much Jews had contributed to world civilization. Perhaps this was what led her to take delight in the company of—to put it as baldly as possible—the right sort of Jews, who nonetheless always remained exotic, not that different from the “negroes” she would mention with a slight reserve, an aloof, almost anthropological interest.

Plath’s furious dismissals of the lowdown Hughes family, who she saw as part of a money economy, suggest they had become synonymous in her angry mind with a certain supposed class of commercial Jews, greasy with the exchange of currencies. In her mind, as in so many antisemitic minds, there was a correlation between that “long Jewish nose, that swarthy look,” and money-grubbing, personified in Uncle Walter, not a Jew but a symbolic Jew nonetheless. Perhaps Plath equated the concept of “Yorkshire Jews” with the grimy kitchen Ted’s mother kept, with the dark, Wuthering Heights look of the land, and the clannish shunning of her exemplified in the rapacity of his sister, Olwyn, who treated Plath as an interloper.

That side of Plath—sussing out suspects, scornful of “Jewy” appearance and behavior—could be set aside for lovely Ann Davidow with her aesthetic interests; for her impressive and attentive mentor, Alfred Kazin; for the Greek-Herculean Mallory Wober and young men like him, as well as for the exquisite Dorothea Krook, so superbly grounded in the philosophy and literature of Western civilization, and Ruth Fainlight, a fellow poet and friend who described herself as “a New York Jew who married out” (to novelist Alan Sillitoe). Like many antisemites, Plath prided herself in the distinctions she could make in her classifications of Jews. Perhaps this made her, in her own mind, a tolerant liberal, ready to appreciate the right kind of Jew, ready even to fall in love with one, but certainly never willing to relinquish an awareness of all those other Jews supposedly demanding their pound of flesh.

Was Plath’s antisemitism unusual for its time? Antisemitic asides of this kind appear, of course, in innumerable diaries, journals and letters and are also woven through British and European, and to a lesser extent American, literature. Plath was hardly worse than her contemporaries, many of whom did not keep her kind of assiduous record of her own daily (and inner) life. The publication of her private writing has not set off the kind of furor that emerged over the diaries of the eminent English poet Philip Larkin, full of disgusting sentiments of all kinds.

Plath is simply not in Larkin’s league of bigots. Her published work, by and large, does not reflect the sporadic prejudices that linger in her letters, journals and diaries. Her hyper-awareness of the Holocaust and empathy for its victims comes through even as she turns them into metaphors. That Plath’s nasty comments about “Yorkshire Jews” seem so shocking may indeed stem from a reader’s keen appreciation of how she rose above such prejudice in her highest achievements.

Carl Rollyson is the author of three books on Sylvia Plath as well as the forthcoming Searching for Sylvia.

Moment Magazine participates in the Amazon Associates program and earns money from qualifying purchases.