Dressing “Unorthodox”: An Interview with Justine Seymour

Costume designer Justine Seymour had never encountered the Hasidic Satmar community before she began working on Unorthodox, Netflix’s recent TV adaptation of Deborah Feldman’s memoir of the same name. The show follows Esty (Shira Haas), a newly married Satmar woman, as she struggles to find her place within the ultra-Orthodox community in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, eventually fleeing to Berlin in search of a new life.

Satmar Jews, like many ultra-Orthodox sects, adhere to strict rules of dress: women must wear skirts, cover their collar bones, wear sleeves down to their wrists and cover their hair once they’re married. Men wear specific shirts, suits and hats, and, after marriage, wear shtreimels (tall circular fur hats) on Shabbat and other festive occasions. Seymour opted for faux fur to create more than 100 shtreimels for the series and won a Peta Compassion in Costume Design Award for her work

Seymour was in Mexico shooting The Mosquito Coast, scheduled to air on Apple TV in 2021, when the pandemic began and she had to return home. Now, she says, after doing a lot of “housekeeping” (taxes, resume updating, etc.), Seymour is ready to get back to work and eager for the television and film industry to pick up again.

Tall and blonde with a striking English accent, her height only slightly less discernible over video call, Seymour spoke to Editorial Fellow Lilly Gelman over Zoom from her apartment in Berlin. She explained how she felt a “heartfelt yearning” for the show since Seymour herself was raised in a religious cult and thrown out at the age of 16. But while she felt an emotional connection to Esty and her story, Seymour’s personal life did not influence her design work, which, she says, is based purely on observation and character development.

How did you prepare for your work on Unorthodox? I read and watched everything that was available on the topic. But none of those films were about the Satmar Haredim. I believe Unorthodox is the first production about that community. So the production team and I also spent a week on the ground in the Satmar community in New York. A young ex-Satmar woman took us on a tour of Williamsburg. She walked us through the streets and talked about the history of the community; where it had started, and how it had fragmented, which was really educational.

I ended up buying all of the men’s clothing in Williamsburg in the dry goods shop there, because, in the Satmar community, the men’s jackets need to button right over left. I couldn’t get anything like it anywhere else. And that shop sold it to me, but a lot of the other shops wouldn’t, so I had to get someone who didn’t look like me, like a tall blonde English woman in red lipstick, to go and shop for me so that they didn’t find it offensive. They just didn’t really want me there.

How did that experience, both the positive and the negative, inform your costume design? It didn’t. I design from observation. There’s no judgment in it. I educate myself first, regardless of whether I’m designing for a religious community or military uniforms or anything else. I go in and get all the information, then I try and put in the little personalized aspects so that the audience can have a visual trigger as to who these people are underneath.

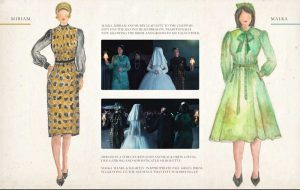

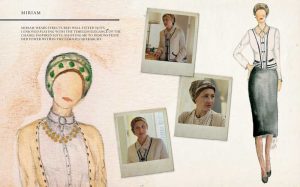

Each character is slightly different. Take, for example, Esty’s Aunt Malka (Ronit Asheri) and her mother in law Miriam (Delia Mayer). Malka is a hustley bustley woman with children and life and business. She’s a “no-nonsense, just get on with it,” type. I wanted her to be quite a colorful character. Miriam on the other hand is more controlled and elegant. She’s a bit older and is the matriarch of the family. I wanted all of that to show within their wardrobes.

How do you begin creating the wardrobe for so many different characters? When I create a character, I look at where they’ve come from, I look at what drives them and how they want to be portrayed. It sounds very intellectual, but I also look into the emotional past of the character. And if it isn’t in the script, then I’ll make it up. And when I do my design presentation to the showrunner, I incorporate my emotional journey for that character and I justify why they’re wearing this, that and the other. It’s quite holistic the way I approach character.

How do you balance accurate design with costumes that feel emotionally accurate? When you’re designing for a television show or movie, you have to stretch it a little bit, which I did with the wedding dress by making it bigger than Deborah Feldman’s. I had been specifically looking for something that looked restrictive, but at the same time could allow Esty to feel like she was the belle of the ball. And Esty was happy, actually, on her wedding day. This was her special day where she was stepping out of childhood into womanhood and she was going to start doing God’s work by creating children. I ended up finding a dress on eBay which I altered a bit for Esty. It was a fine line to tread between making her look tight and restricted and unable to move, and at the same time celebrating her happiness. And when I look at Deborah’s wedding photos side-by-side with images from the show, they feel really similar emotionally for me.

Top: Photo from Deborah Feldman’s wedding; Bottom: Still from Esty’s wedding scene in Unorthodox.

I did change the last headdress from the wedding. I wanted the three stages of the wedding to be visually easy for the audience to understand, even though it wasn’t technically correct. She starts off with one veil, and then she moves to the shroud that covers her face to get married, and then she goes to the big turban-y piece. That’s where I used my suspension of disbelief.

But you have to remember that I need to choose clothing that is also going to work with how we’re shooting. Do I have a stunt double? Do I have a stand-in? Is there a fight? Are they going to rip something? For instance, when Esty leaves the States, it’s Sabbath morning, but I couldn’t dress her in Sabbath clothing because I needed her to leave New York and arrive in Berlin and not look like a completely strange person standing out on the street. I also needed her to go and meet the musicians, and then I needed her to go to the beach and walk into the water. And whenever something gets wet on set you have to have four of the same outfits so you can immediately change them because you never get the shot on the first take. So I have to keep in mind the technical side of what the wardrobe is doing within the scene.

How did you use costume design to portray Esty’s journey out of the Satmar community? I met with Deborah Feldman to discover her perspective on what it’s like to go from having a very specific dress code to having more freedom in that area. I wanted to know, once she made that decision to leave, how long it took her to experience trying on clothes that weren’t in her comfort zone. And it took a long time. We used that experience within the show.

I wanted Esty to let go of the dress code very slowly, so I kept tiny references to her old life. When she first changes out of the clothes she traveled in, she’s got on a cardigan that’s buttoned all the way up, and she’s wearing a scarf. She hasn’t got it on her head, but she has got it on. I even kept Esty in her original skirt for that change. And then I progressed slowly into her wearing jeans and some more open tops. But I kept very sensible shoes on her the whole time, nothing airy and sandaly about them. Deborah had told me that she never felt comfortable wearing short sleeves or sleeveless tops, so I tried to keep Esty away from that as well.

I also incorporated the idea that when she met her new friends in Berlin, she observed how they were dressed and took information from them. I copied them a little bit for Esty’s new style. It’s quite subtle, but I think that good design is not noticed. If you really pulled apart the design, you could see where she borrowed what, where she noticed what they were wearing and that she’s emulated it. It’s a lovely progression.

How did you show Esty’s feelings of suffocation within her community without making a critical statement about the Satmar community as a whole? I never wanted to be critical. People’s religious choices are personal. But I did want the wardrobe to feel a bit restrictive. We had so many extras and none of them were actors, and I wanted them to feel that restrictiveness. We were shooting during a heatwave in Berlin, and with the amount of clothes they had on it was quite uncomfortable for them, but at the same time it added an awareness of their clothing that added to the way the extras behaved.

For Esty in particular I just tried to be as truthful as possible. There was a scene where she’s standing in her new apartment and says to her aunt that she doesn’t want to be married anymore. For that scene, I made her dress just slightly too big for her so she just looked like she was being swallowed up by the clothing, and she looked slightly out of place being there in the kitchen standing by the window. That was a little trick I used.

Men in the Satmar community have a little more freedom and autonomy in their lives. Did you portray that in the costumes? I gave a bit more liberty to Moishe (Jeff Wilbusch) because he had left the community and come back. I wanted to show his tumultuous undercurrent. He’s trying to get back into the community but also has some addictions, to gambling for example. And because he’s this kind of bad guy, I also wanted to play with his sex appeal as well so that he could have an edge.

I made Moishe’s suit navy blue with a stripe inside it, rather than everyone else who wore black or very deep gray. I also gave him nicer shoes; just subtle things so that it felt like he didn’t quite fit either.

Esty’s father, Mordecai (Gera Sandler) also had a slightly different wardrobe. He was an alcoholic, so I made him much schlumpier. And then we chose this really old fashioned hat for him because I wanted him to stand out as someone who wasn’t interested in keeping up with the fashions.

What happened to the costumes once the show finished filming? Generally, if you go to Warner Brothers in Los Angeles, there’s this massive, massive archive of costumes that you can actually go in and rent from. But when I came to Berlin and I was looking for Jewish clothing, there was nothing available at all. So after we finished, I asked the production company to donate the shtreimels to a theatre company in Berlin so that if there was another production that came into town they were there and they were safe. We also donated most of the men’s clothing to the Satmar community in Manchester because Jeff Wilbusch’s family is from there and he asked.

One thought on “Dressing “Unorthodox”: An Interview with Justine Seymour”

Amazing So enjoyed this interesting and informative description of the journey of Justines costume design SO thorough and attention to detail and historical design