Six fateful days in 1967 fundamentally altered the map of the Middle East and shaped the course of history in the region for decades to come. On the 50th anniversary of the Six-Day War, Moment reached out to an eclectic group to ask: which event most defined the last half-century of the Israeli experience?

Click a name to jump to their answer:

Mustafa Barghouti / Avraham Burg / Yael Dayan

Matti Friedman / Yossi Klein Halevi /Fida Jiryis / Daniel C. Kurtzer

Dov Lipman / Sherri Mandell / Eilat Mazar

Yisrael Medad / Aaron David Miller / Benny Morris

Mark Podwal / Dorit Rabinyan / Meir Shalev

Raja Shehadeh / Ksenia Svetlova / Ayelet Waldman

Symposium Editor Marilyn Cooper

Interviews by Marilyn Cooper, Dina Gold,

George E. Johnson, Ellen Wexler, Laurence Wolff

Meir Shalev

Meir Shalev is an Israeli author and journalist. he writes a column for the daily newspaper Yediot Ahronot. His novels include A Pigeon and a Boy and, most recently, Two She-Bears.

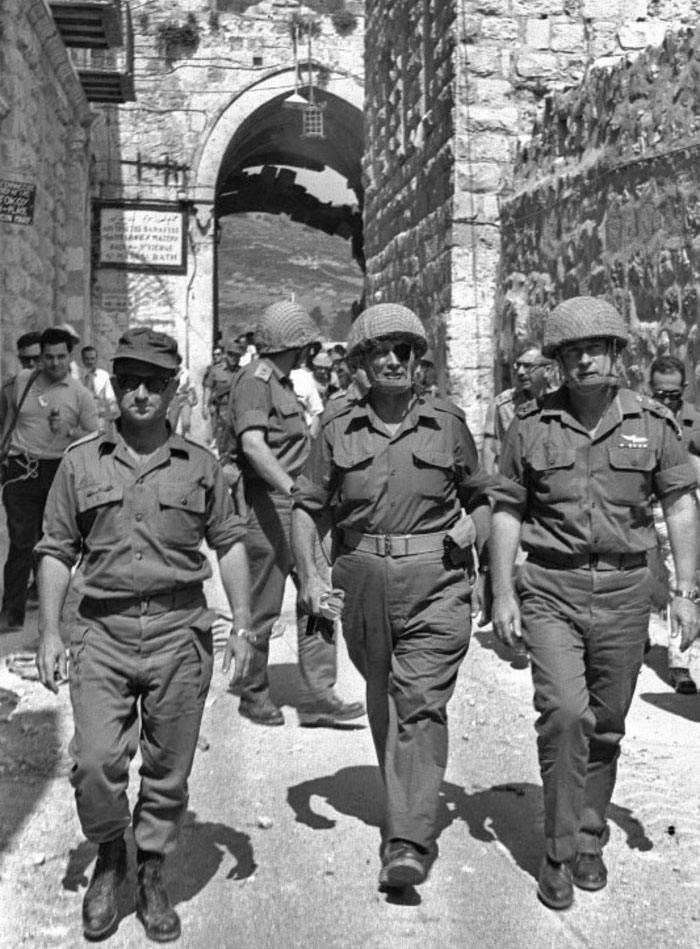

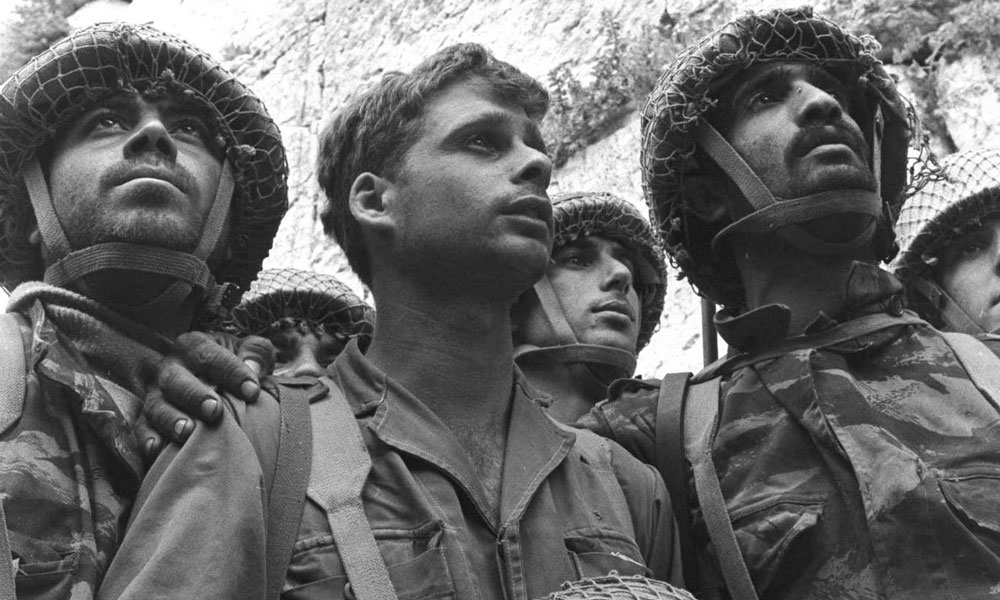

I was recruited into the Israeli army in 1966; I was dismissed from service in 1968 because of an injury. I always felt I was recruited into the army of one country and left the army of a completely different country. I fought in the Six-Day War in the Golan Heights in an elite group, the reconnaissance unit of the Golani Brigade. We fought in fierce battles over the Golan Heights. We were very eager to fight. The fighting itself was very intense; I lost some good friends in it. Back then I felt like a victorious soldier; now I look at it with very different eyes.

Before 1967, Jerusalem was a wounded city; it was divided in two halves. Jerusalem had a frightened and reserved feeling. People on the west side felt disconnected from the Mount of Olives and the Temple Mount. It was a very cultured city with the only university in Israel and the seat of the government. The first years after the Six-Day War were the most beautiful years in Jerusalem. Young people came from Europe and the United States. We didn’t have television or internet and very few people could afford to go abroad, but suddenly abroad came to us. Everyone admired Israel. Young people came from around the world and they brought us two new toys, the Pill and grass. We had not known them before; suddenly Jerusalem became very happy! This was only for a few years, and slowly it went back to what it used to be. Today Jerusalem is a vulgar city with religious fanatics, the way it has been for most of its history.

My father, the right-wing poet Yitzchak Shalev, was in a state of complete euphoria after the war. About a month and a half after it ended, I spent a weekend leave from the army with my family. My father and I got into a big fight, I told him that with this victory Israel had taken a bite that we would suffocate on; he kicked me out of the house. I wasn’t speaking from political or ideological reasons but practical ones. I thought that a nation of three million people couldn’t rule a nation of one million people. It’s impossible unless you dedicate all your resources to it. That’s what’s happened for the last 50 years. It’s a tragedy for the State of Israel.

Yael Dayan

Yael Dayan is an Israeli politician and author. She served as a member of the Knesset between 1992 and 2003, and from 2008 to 2013 was the chair of the Tel Aviv city council.

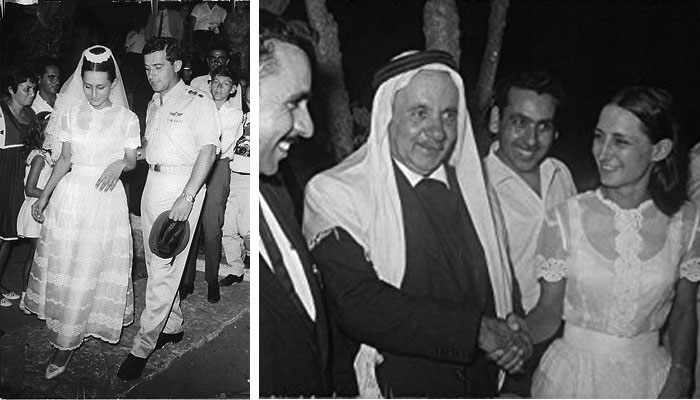

I got married the July after the 1967 war; I had been a reserve officer in the war, a lieutenant in the unit under the command of General Ariel Sharon. I married a colonel I had met during the war; he was Ariel Sharon’s right-hand man, Sharon was my husband’s best man. My father, Moshe Dayan, was minister of defense, and the wedding was in my parents’ house in the Tzahala neighborhood of Tel Aviv. We invited family and friends, and my father added as invitees all the mayors of the West Bank and the Gaza cities. They all came to the wedding; this was pre-Palestinian Authority. It was a marvelous feeling, like a promo for peace. Here we were, the bride and groom, the chief rabbi of the army, David Ben-Gurion, and all the big Palestinian West Bank and Gazan families. It was an unforgettable event coming immediately after the war; it showed our belief that we were now on the road to peace.

I remember when my father declared the reunification of Jerusalem. People my age and older had a tremendous feeling at that time that this was the war that would end all wars. We believed that the extent of this tremendous victory would mean a ticket to peace. There was a huge difference between one month after the war, one year after the war, ten years after the war, the 1973 war and this current landmark—all of which were a series of disappointments as a result of all that was not achieved by the 1967 war. Today, we are at the peak of the disappointment. Rather than planting a seed leading to a peaceful coexistence and a solution to the conflict, the war sowed a seed which has grown into a great catastrophe that is endangering the existence of the State of Israel: the rise of extreme religious elements, the rise of the far right and a kind of imperialism which has come to endanger our democracy. Instead of Israel meaning a homeland for the Jews, we Israelis have become an occupier of another people’s homeland.

It’s unbelievable after 50 years not to have found a solution for such a minor problem as the little Palestinian-Israeli conflict; it’s really very small when you think of huge global problems. But then we have become some kind of monster. I say this as a patriot—don’t misunderstand me. I live here; I have children, grandchildren here. My father and mother fought for peace, they believed in the importance of cooperation and coexistence. Their hopes have been disappointed.

Raja Shehadeh

Raja Shehadeh is a Palestinian author and lawyer living in the West Bank. He founded the human rights organization Al-Haq. His most recent book is Where the Line is Drawn: A Tale of Crossings, Friendship and Fifty Years of Occupation in Israel-Palestine.

For me, the most pivotal moment for the State of Israel in the past 50 years took place very soon after the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories. On Saturday, June 10, 1967—literally the last day of the 1967 war—my father, Aziz Shehadeh, approached the Israeli government with a written plan for peace negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians in both the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The core of the plan was the establishment of a Palestinian state in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip alongside Israel with its capital in East Jerusalem and an equitable solution for the Palestinian refugees. It had the support of some 50 Palestinian leaders in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. I helped my father by typing the plan on my manual typewriter.

Over the past 50 years there were a number of other opportunities for peace that Israel squandered. But perhaps that first one, which took place before the occupation had become entrenched and a large number of Israelis were moved into Jewish settlements in the West Bank, was the most decisive and could have changed the course of the history of Israel, Palestine and the Middle East region as a whole. Had this plan been seriously considered by the Israeli government, we Palestinians would have been spared 50 years of suffering under a brutal occupation, and the Israelis would have been rid of what Gideon Levy, the Haaretz columnist, has recently described as “the greatest Jewish disaster since the Holocaust.”

It was only years later, after reading The Bride and the Dowry by Avi Raz, that I learned that the Israeli government did not even bother to discuss the plan. Israeli leaders were so drunk with victory that the then Israeli minister of defense, Moshe Dayan, declared soon after the end of the war: “We are now an empire.” I was then a 16-year-old who had little interest in politics, yet I could see how disappointed my father felt when, three weeks after the occupation, he learned that “the empire” passed a law on June 27, 1967, annexing East Jerusalem, which he had proposed should be the capital of the Palestinian state.

Yisrael Medad

Yisrael Medad is an American-born Israeli journalist. He was the editor of Counterpoint and the founding editor of Yesha Report. He is currently the Director of Educational programming and Information Resources at the Menachem Begin Heritage Center in Jerusalem.

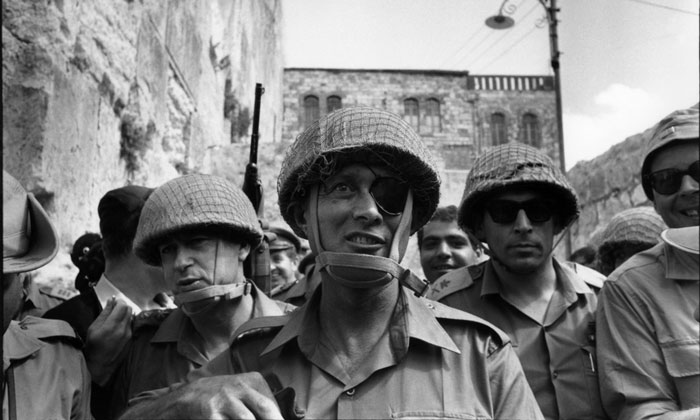

The reunification of Jerusalem was a key moment in the continuing battle for the soul of Jewish national identity. The official decision for reunification on June 27, 1967 by the Knesset came after 19 years in which most of the world had been very critical of Israel for moving its capital to Jerusalem. The reunification created a strong connection between Jewish history, Jewish culture, the Jewish religion and Zionism. Jerusalem is at the heart of who we are as Jews and Zionists. I remember crossing over the Green Line with friends and celebrating the reunification at the Western Wall. I felt I was a foot and a half off the ground. It was an exuberant time.

Today, I live in Shiloh and consider myself to be an unofficial spokesperson for the Jewish communities in Judea and Samaria. The settlements are all suburbs of Israel, but Shiloh is a special case because that is where the Tabernacle was erected; for hundreds of years Jews came from all over to worship here. When I greet visitors at Tel Shiloh I tell them, “Remember that to get to Jerusalem, you have to come through Shiloh first.” Archeological digs at Shiloh have proven that Jews lived there in biblical times and much later. This refutes the notion that Jews were physically exiled. We only lost political and military power; we always continued to be in this land and the idea of Jerusalem kept us alive and sustained us for centuries.

There has been an Arab usurpation of the Jewish patrimony of Jerusalem. The framework of this argument, what I call Palestinianism, is basically, “Who cares that you were here 2,000 years ago, we’ve been here for 1,300 years.” Arab political propaganda claims that Jerusalem is an “Arab city” and that it has been a holy Islamic city for centuries. This is false, Jerusalem as a city has no significance for Islam; it is not mentioned even once in the Quran.

After 1967, the poet Natan Alterman wrote, “This victory effectively obliterated the difference between the State of Israel and the Land of Israel. It is the first time since the Second Temple’s destruction that the Land of Israel is in our hands.” Shiloh and other communities in Judea and Samaria are part of that return to the land.

Daniel C. Kurtzer

Daniel C. Kurtzer is the S. Daniel Abraham Professor of Middle East policy studies at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. From 2001 to 2005 he served as the United States Ambassador to Israel and from 1997 to 2001 as the United States Ambassador to Egypt.

Israel’s victory in the 1967 war changed everything. Israeli power was on display, in sharp contrast to the weakness of surrounding Arab states. The idea of pan-Arabism died, and Palestinians assumed responsibility for their own fate. Relations between the United States and Israel blossomed, ultimately becoming strategic assets for both countries. And Israel’s occupation began amidst indecision on the part of the Israeli government and nascent messianic fervor among segments of the population.

I spent eight weeks in Israel that summer, first as a volunteer helping to clean up the Mount Scopus campus of Hebrew University and later as a tourist. That visit, and the mixture of unbounded exhilaration felt by the Israeli population and numbing depression in the West Bank and Gaza, stimulated my interest in working toward peace between Israel and its neighbors, something I have pursued professionally and academically for the past 50 years.

Even though the war had ended only ten days before my arrival in Israel in June 1967, the country was wide open. I recall hitchhiking to Gaza, wandering around the town and being invited by IDF officers to join a three-day bus excursion into the Sinai, where the remains of war were still in plain view. I recall meeting my relatives—Holocaust survivors—for the first time and experiencing vicariously the relief they felt in contrast to the fears that had built up in the weeks before the war. I remember the crowds that poured into the Old City of Jerusalem, curious to experience the Western Wall; and I recall the faces of the Palestinians who watched these crowds pass by with a mixture of anxiety, anger, animosity and depression.

Years later, my parents told me that the letters I wrote home that summer (before email was invented and when the price of an international phone call still broke the bank) told of my belief that the euphoria would not last and that the reality of dealing with an unhappy population under occupation would necessitate a peacemaking effort. I don’t recall those letters, and they are now nowhere to be found; however, the feeling that my parents say I expressed in July and August 1967 clearly motivated me to try to do my part to bring peace to Israelis and Arabs. So far, little success, but I have not lost hope.

Ayelet Waldman

Ayelet Waldman is an Israeli-American author of fiction and nonfiction. Most recently, she and Michael Chabon edited Kingdom of Olives and Ash: Writers Confront the Occupation.

The Six-Day War plays a critical role in my personal history, despite the fact that I was a very small child at the time. I was born in December of 1964. In 1967 my family was living in Jerusalem. The very first memory I have, a hazy one that I’m not sure is even real, is of being in either a basement or bomb shelter with my mother. My siblings were not there, and my understanding is that my mother didn’t know where they were. We left Israel right after the war. My parents had already planned to leave—my father was back in Canada looking for work when the war broke out—but the war was the last straw.

The Six-Day War catalyzed so much of what has happened since. It allowed not just Israelis but also the Jews of the diaspora to see themselves as heroes rather than merely victims of the Holocaust. And of course, it was the beginning of this period of occupation and colonization. The occupation itself, not enemies on its borders, is the greatest threat Israel faces. I believe that the act of colonization, of being an occupying force, could well lead to the destruction of the State of Israel.

As an adult I’ve traveled in the occupied territories. One of the most horrible and compelling places I visited was the two villages of Susya, the Palestinian village and the Israeli settlement. For decades, perhaps even as long ago as the early 19th century or before, there had been a Palestinian village there, a community living in caves and caverns. The Israeli government used the excuse of the archeological importance of the site to remove the residents. However, once they were gone, a settlement was built. I stood on the barren hill outside the settlement, amidst the hovels to which the Palestinian families have been reduced, without any of the basic human necessities such as running water and electricity. They live in abject poverty. Periodically their shanties are bulldozed and their wells are despoiled as the Israeli military seeks to drive them from their homes. In the distance you can see the pretty little settlement, with its gardens and irrigation, its synagogue and kindergarten. The contrast is nauseating. That’s the legacy of the 1967 war.

Eilat Mazar

Eilat Mazar is a third-generation Israeli archeologist. She specializes in Jerusalem and Phoenician archeology and has worked on the Temple Mount and City of David excavations.

After the Six-Day War, Jerusalem was united again. It was obvious to me that Jerusalem should be one city and the capital of Israel. It is a city that Jews own by historical right. Separating east and west Jerusalem is like cutting off the legs of a person. Ancient Jerusalem started in a place we now call the City of David in the eastern part of the city, which I helped excavate. This is where Jerusalem began and then it developed towards the Temple Mount; that is the heart of the city. Archeology definitely proves that Jews were the first to be in Jerusalem. The most ancient parts revealed by our excavations contained Hebrew. Other languages only appeared much later. Jerusalem later came to be important to Christians and Muslims; they should be part of the city and respected. But first and foremost, it is a Jewish city—that is unquestionable.

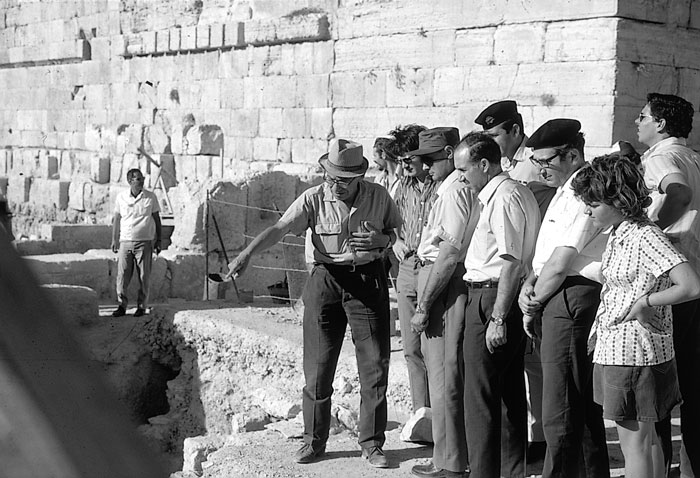

I first went to east Jerusalem in 1968 to see my grandfather Benjamin Mazar’s excavation at the foot of the Temple Mount; I was 11 years old (photo above). The western part of Jerusalem was already very developed and beautiful, but until then the eastern part was disgustingly unkempt. It was very dirty and messy, the roads were poor and the whole area had been horribly neglected. You had to tour the site quietly because it was also dangerous. There was worldwide interest in the excavation. Changes were already taking place, people were eager to develop it. Archeology was part of the work of developing east Jerusalem; we made it so you could appreciate and enjoy the heritage of east Jerusalem.

Yossi Klein Halevi

Yossi Klein Halevi is a senior fellow at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem. His most recent book, Like Dreamers, took the top prize at the 2013 National Jewish Book Awards.

The first time I visited Israel was as a 14-year-old boy in the summer of 1967, a few weeks after the war. I was on a one-year program at Hebrew University in 1973 when the Yom Kippur War broke out. I moved to Israel in 1982 at the beginning of the Lebanon War. I was drafted during the first intifada. I feel like my life has been on a trajectory with Israel’s wars.

Encountering Israel for the first time in the summer of 1967 was meeting Israel at its most euphoric moment. It was the happy ending of Jewish history. Everyone you spoke to that summer said, “That’s it, it’s over, no more wars.” There was a feeling of completion. Everything was magical; everything was whole. There was the sense that Israel was compensating for everything that we’d lost. My father was a Holocaust survivor, and he came out of the Second World War angry at God. And in the summer of 1967, standing at the Wall, he made his peace with God, and he said to me, “Now I can forgive God.”

Six years later, I returned to Israel as an overseas student and the Yom Kippur War broke out. The experience of being in Israel during the country’s most devastating moment was the exact opposite of how I had first encountered Israel. When I watched my Israeli friends and cousins go off to war while I stayed behind on the home front, I felt ashamed. My generation of Israelis was defending the country, defending the Jewish people, and my American privilege had bought me an exemption from this part of Jewish history. I realized I didn’t understand Israel. I was a well-wisher looking in from the outside.

One incident haunted me for years. I was walking on the streets in Jerusalem when a jeep passed with some soldiers in it and one of them called out to me, “Can I have your scarf?” And I said no, because what I had learned about Israel before the war was, “Don’t be a freier, don’t be a sucker.” What I didn’t realize was that “don’t be a freier” applies only to Israel when it’s not in a state of emergency. When it’s in a state of emergency, everyone is expected to give everything. Afterward, I realized that guy wasn’t trying to rip me off. He was a soldier, and he was reaching out to me because he assumed that I was a fellow Israeli and that I knew the code and that of course, I would give him my scarf—he asked for it. He needed it, and he was going back to the front, and I wasn’t on the front.

That was the moment when I decided that I wasn’t going to be an outsider to this story. Experiencing Israel in 1967 made me want to be a part of Israel, but experiencing Israel in 1973 made it essential for me to be a part of Israel. In retrospect, that was the moment when I decided to make aliyah.

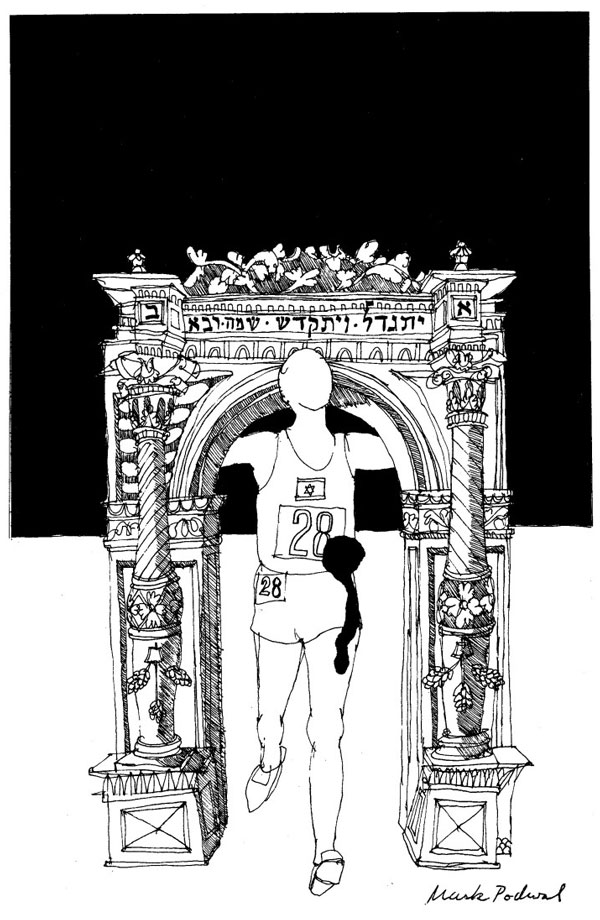

Mark Podwal

I remember watching the coverage of the September 4, 1972 massacre of Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics on television and the indelible image of the terrorist in a mask on the balcony. It was a horrifying event that showed the dangers Israelis faced no matter where they went in the world, even when they were supposed to be protected. Distressed by the appalling tragedy, I expressed my feelings through a drawing that was later published on the Op-Ed page of The New York Times. The black and white ink drawing portrayed an athlete crossing a gate resembling the gate on the title page of a Hebrew book. In Hebrew, the title page of a book is called sha’ar (gate), the portal through which one enters the holy text. The gate in my drawing represented both a finish line and the gate to heaven. Instead of the Hebrew inscription on a title page gate, which reads, “This is the gate the righteous shall enter,” I wrote the first Hebrew words of the Mourner’s Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead. On the athlete’s chest a blot of dripping ink indicated blood spilt. The cartoon struck a nerve for many people; it helped people identify with this great tragedy.

Mark Podwal is an artist, and a dermatologist at the New York University School of Medicine. His drawings have appeared on The New York Times Op-Ed page and his art has been displayed in museums around the world.

Avraham Burg

Avraham Burg was chairman of the Jewish Agency for Israel from 1995 to 1999 and Speaker of the Knesset for the Labor Party from 1999 to 2003. In January of 2015, he joined the Jewish-Arab Hadash Party.

The visit of President Anwar Sadat to Israel in November 1977 was a pivotal moment. His initiative brought with it the whole package of peace with Egypt. It was the first time that Israel had the opportunity to change the language from the vocabulary of war and conflict to that of peace and reconciliation. After the trauma of the 1973 war, this offered Israel a new direction with so many different possibilities. I was recruited into the army in the middle of the 1973 war, and I found myself, by the end of that war, on the other side of the Suez Canal defending myself from Egyptian commandos. The 1973 war crushed Israeli arrogance and was the worst period for the country’s feeling of military insecurity.

When Sadat arrived in Jerusalem, I had already been released from my army service and I ran behind his convoy with my colleagues and friends chanting loudly, “No more war, no more bloodshed.” There is no doubt that in Israel then there was an energetic transformation from feelings of fear to hope and euphoria. In April 1982, Israel finalized the withdrawal from Sinai and immediately after, in June, invaded Lebanon. This first war with Lebanon put an end to the five years of Sadat’s offer of a new language. I found myself, as a young officer in 1982, commanding my troops in Lebanon. The same Menachem Begin government that had made peace embarked on a war of folly and deceived the people and the government into this endless cycle of violence.

Dov Lipman

Dov Lipman is an American-born orthodox rabbi and Israeli politician. He served as a member of the Knesset for the Yesh Atid party between 2013 and 2015. He currently serves as director of public diplomacy at the World Zionist Organization.

When Israelis evacuated Ethiopians from Sudan in Operations Moses (1984-1985) and from Ethiopia in Operation Solomon (1991) the country fulfilled part of its intended role. Because of the Holocaust, we often talk about Israel as a place of refuge, but the real reason for the establishment of the State of Israel is the return of the Jewish people to their home. I’m not criticizing anyone for living in the diaspora, but that’s not our natural place to be. Our natural home is the land of Israel, and this is where we can become a great nation. The Ethiopians were Jewish but they were not connected to the Jewish people, and while they weren’t facing specific persecution their lives were very difficult. The State of Israel intervened and went in to get them out. These Jews walked in deserts for months, with significant numbers dying, in order to come back to their homeland. They were coming because, for thousands of years, they had this dream of returning to their home. This, I believe, reminds us of what’s ultimately important here. This is the land that God gave to us, as a people, and this is where we can reach our potential as a nation, and best impact the world.

I wanted to support the new immigrants, so I volunteered with Ethiopians housed at the Diplomat Hotel in Jerusalem and played with their kids. They had nothing to do. They were in this hotel as Israel was trying to figure out where they should live. I would talk to the adults through translators. They had a gleam in their eyes because their dream had come true. One of them said to me, “When do we get to see the big house?” I said, “What are you talking about?” Through the conversation, we discovered that they were expecting to go see the Temple. They did not even know of the destruction of the Temple.

The State of Israel brought them here with incredible determination and sacrifice, but there wasn’t much thought about what to do with them after they arrived. So they have struggled, but it’s not because of some kind of ingrained or systemic racism in Israel. There are opportunities for them here, just as there are for Arab-Israelis. Privately many Arab-Israelis have told me that despite the difficulties they would rather live in Israel than any other country in the Middle East and that they appreciate the rights they have here. Israel is a work in progress, and part of re-establishing the Jewish homeland is making sure that all those living in our midst—including non-Jews—feel completely comfortable.

Ksenia Svetlova

Ksenia Svetlova is a Russian-born Israeli politician, journalist and academic. She serves as a member of the Knesset for the Zionist Union.

© Zion Ozeri

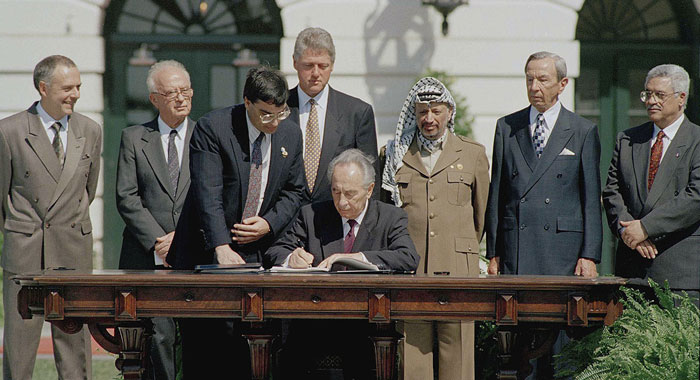

I may sound overly idealistic, but the 1993 Oslo I Peace Accord was a very important moment in Israeli history. Today, many people think that it was a tragic moment that resulted in many deaths without producing peace. But I believe it showed everyone that if there is a will, there is a way. Something that had seemed utterly impossible before the accord suddenly became a possibility. The first steps on the road to peace were taken. Unfortunately, the next elected leader after the slain Yitzhak Rabin, Benjamin Netanyahu, chose not to take the path of peace.

In 1993 I had only been in Israel for a few years; my family had recently made aliyah from the USSR. I enrolled in a school that could most accurately be described as a settler’s school. Most of my friends and classmates lived in the Israeli settlements, and I heard few positive comments or accountings of the Oslo Accords. They were all extremely negative about the peace process and cursed Yitzhak Rabin. They said that the Oslo Accords would result in tragedies and that you could not trust Arabs. I was raised in Moscow in an enormously different political climate. There is a lot of nationalism there now, but that was not the case in the 1980s. It was very disturbing and upsetting to me to hear Israelis say derogatory things about Arabs. Some of what they said reminded me of anti-Semitic phrases I heard people say to my family back in the USSR—like “you cannot do business with the Jews” or “you cannot trust the Jews.” I was so sad to hear Jews speak that way.

Mustafa Barghouti

Mustafa Barghouti is a Palestinian physician, activist and politician currently serving as general secretary of the Palestine National Initiative, also known as al Mubadara. He has been a member of the Palestinian Legislative Council since 2006 and is also a member of the Palestine Liberation Organization Central Council. He was the minister of information in the Palestinian unity government.

I was most hopeful for peace in the region when the first intifada started. I felt that the popular uprising would challenge the Israeli occupation and that it would not continue. The moment I remember most was in 1989 when, after months of organizing, we came together, Israeli peace activists and Palestinian peace activists, and created a human chain for peace around the walls of the Old City in Jerusalem. We stood hand in hand, Palestinian and Israeli civilians, forming a huge circle of people for miles all around Jerusalem. We waved olive branches and danced and sang together; we talked with one another. It was a great moment. I felt very hopeful. Other people from all over the world—Americans, Europeans, nuns and monks—perhaps 15,000 of us in total, participated in this peace chain. There were people who walked for many miles to be there. Later the Israeli army attacked us. I remember an Italian woman lost her eye to a tear gas bomb, and one of my colleagues was hurt and lost his hearing. But even so, this was a moment of friendship when I felt peace was possible.

Benny Morris

Benny Morris is an Israeli historian and journalist. He is a professor in the Middle East studies department of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. He was formerly a correspondent for The Jerusalem Post. His most recent book is One State, Two States.

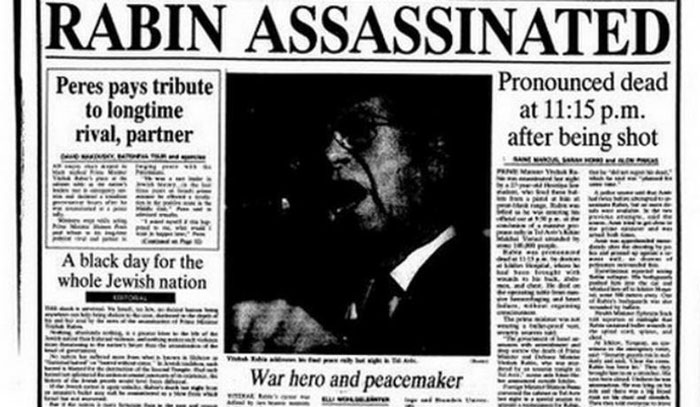

The assassination of Yitzhak Rabin was symbolic of the ascendance of the Israeli right; it marked the end of the peace regime. I distinctly remember where I was when it happened. My wife and I had been at the peace rally at Kings of Israel Square in central Tel Aviv. Rabin was shot, assassinated, at the end of the rally. Wanting to avoid the heavy traffic that was expected at the end of the rally, we had left a few minutes early. As we approached our friend’s house in northern Tel Aviv, a neighbor shouted to us from her balcony that Rabin had been shot. This was just a few minutes after we had left the site. It was truly shocking news. We had a clear sense at the time that this was a devastating blow to the left and to the peace process.

Sherri Mandell

Sherri Mandell and her husband founded the Koby Mandell Foundation. Mandell wrote The Blessing of a Broken Heart about the murder of her son, Koby.

The most pivotal moment was the 2005 withdrawal from the Gaza Strip and the subsequent exhumation of the Gush Katif cemetery. Gush Katif was a series of 17 settlements. 8,600 people lived there; it was a mixture of religious and non-religious people founded in 1968. In 2005 the Israeli army forcibly removed Jews from this land as part of the disengagement from Gaza. In a violation of Jewish religious law, later 46 bodies were exhumed from the graveyard and moved to Jerusalem. Some had died in the military, others from terror or illness. A procession of hundreds of people marched behind the coffins through the Old City to the Mount of Olives. I was there, I walked with them and it was shattering. Almost all the people watching were religious. That was also devastating because I felt that the entire nation should have been there to witness this moment.

Dorit Rabinyan

Dorit Rabinyan is an Israeli author. Her most recent book is All the Rivers, which won the Bernstein Prize.

It was 1995, I had been released from the army and I wrote and published my first novel. I was 22. This was a very prosperous time for Israel and for me. The first time I voted for prime minister was for Yitzhak Rabin. I felt I had beginner’s luck. I was drunk with the success of my vote because he was such an inspirational and responsible leader. When he negotiated the Oslo Accords (Oslo II was signed in 1995) I thought he was omnipotent. It made me believe that anything was possible. The Oslo Accords were innovative; they showed that dialogue was a real option and that we didn’t have to rely upon the old methods of military force and occupation. As Israelis, we were choosing to relate to our neighbors as equals, as our partners, and acting with the belief that we all could and should feel hope for future generations.

The signing of the Oslo Peace Accords formed my political point of view and shaped me as a human, as a writer and as a woman. My parents emigrated from Iran to Israel. Had they not, I could easily have been the next in a long chain of women to struggle with life under a patriarchal, domineering and very repressive regime. I credit Zionism and Israeli democracy with redeeming me from that destiny. I see myself as a product of Rabin’s brand of Zionism; so much of who I am, of my liberty as a woman, my freedom of thought and speech relates to that philosophy. The Oslo Accords were a promise to me and to my generation from Rabin as our leader that the world was going to be a different place. In Israel, unlike Iran, as a woman, I could vote safely. Rabin’s actions with the Oslo Accords made me believe that my vote could change the world; as an individual I could help shape my destiny.

Twenty-two years later, I feel that the Oslo Accords and the subsequent failure of the peace movement show both the strengths of Israel and its weaknesses. I still believe in the potential for peace. Once you have tasted a drop of the possibility of peace you cannot forget how empowering and magical it is. Ever since, I have been thirsty to taste it again.

Fida Jiryis

Fida Jiryis is a Palestinian writer, editor and the author of Hayatuna Elsagheera (Our Small Life), and Al Khawaja (The Gentleman), She is currently completing a third collection of Arabic short stories, Al-Qafas (The Cage) and an English memoir, My Return to the Galilee, on her return to Palestine after the Oslo Accords.

With the signing of the Oslo Accords on the White House lawn on September 13, 1993, Israel had a historic chance to make peace and try to repair, though never erase, its dispossession of the Palestinian people. Instead, the tragic consequences of the Oslo Accords were a far worse reality than the one that had preceded signing them.

I was living in Cyprus at the time. My father, Sabri Jiryis, a Palestinian from the Galilee, had been in exile from Israel for 23 years. A graduate of law at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, he had co-founded Al-Ard resistance movement in the 1960’s to demand a solution to the conflict, the establishment of two states and the return of the Palestinian refugees. He was heavily harassed by the Israeli authorities, and eventually had to leave the country and headed to Lebanon, where he later became the director of the PLO Research Center in Beirut. In 1983, in the wake of the Israeli invasion of Lebanon the preceding year, the research center was bombed and my mother, seven other employees and many passersby were killed. After this we moved to Cyprus.

In 1993, when the Oslo Accords were signed, my family and I sat glued to the TV set, not believing what we were seeing. Two years later, we were able to return to our village in the Galilee, for the first time in my and my brother’s lives, and my father was able to return and reinstate his ID, giving us citizenship as well. The chapter of exile was closed. We were a unique case; the Accords allowed for a very small number of Palestinians to return to their towns or villages inside Israel, and only a handful of people are estimated to have returned in this way.

To me, this major historic event had a direct, powerful impact on my life; I’d grown up a Palestinian and witnessed a tragedy similar to many other Palestinians, and dreamt of my homeland, my return to which had been impossible. Overnight, I was able to return, after never imagining that this would happen.

Going to Israel was a profound shock; I was not prepared for the difficulties of integration as a Palestinian and the systematic discrimination I would face in the state. It took me many years of struggle to understand that I would always be a member of a looked-down-upon, struggling minority and that being an Arab meant being treated very differently from being a Jew; I would never feel equality or inner peace in a state that practices overt and subliminal violence every day.

Aaron David Miller

Aaron David Miller is the vice president for new initiatives and a distinguished fellow at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. He has served as an adviser to Republican and Democratic secretaries of state, most recently as the senior adviser for Arab-Israeli negotiations.

On a rainy Saturday morning, November 4, 1995, I was driving to the dry cleaners in Washington, DC, glued to the local all-news radio, when I heard a sketchy report that Israeli Prime Minister Rabin had been shot while exiting a peace rally in Tel Aviv. I immediately called the State Department Operations Center; they confirmed the report and later that Rabin had died. If you asked me to identify one event in the past 50 years of Israel’s history that was both truly consequential and personal, for me it would be Rabin’s assassination.

Men, Karl Marx wrote, make history, but rarely as they please. Yitzhak Rabin made history throughout his extraordinary life, but most heroically and tragically as a would-be peacemaker—a transformed hawk who gradually came to understand that the Palestinian problem threatened Israel’s security and values and that, because there was no military solution, Israel had to embrace, however cautiously, a political one. The result, the Oslo process, defied history, but it later collapsed under the weight of huge differences between Israelis and Palestinians and fundamental disagreement over process, substance and deep-seated suspicions and fears.

Rabin’s death was also a personal and not just a professional matter for me. He was close to both of my parents and I had gotten to know him years before I worked as a State Department analyst and negotiator. At the funeral in Jerusalem, the memories flooded over me: the Passover seder at Rabin’s apartment in April 1974 shortly before he became prime minister, where in his gruff but wonderful manner he told me I knew nothing about the Middle East. My wife Lindsay and I had been in Jerusalem the preceding year during the October 1973 war. And almost 20 years later, I recalled being with Rabin for another Jewish ritual—this time as part of Secretary Warren Christopher’s first visit to Israel and a Shabbat dinner Rabin held in his honor. I remember Rabin asking me to do the Shabbat Kiddush, and how surprised the secretary was to see Rabin turn to me to do the honors.

I miss Rabin. He was neither a saint nor a water walker. He had flaws and imperfections. But he had authenticity as a leader and the pragmatism and vision so rare in Israel, let alone in the Middle East today, but so critical to wise and effective leadership. There are no rewind buttons on history. But I have said many times that, if I could alter two things, Rabin would not have been murdered and George H.W. Bush and his eminently talented Secretary of State James Baker would have gotten another term—then we might have been able to achieve an agreement. I often question that judgment now as the Middle East continues to melt down. But with respect to Rabin, of this I am certain. Israel, the Middle East and the world are so much poorer and emptier without him.

Matti Friedman

Matti Friedman is a Canadian-born Israeli author and journalist. He wrote The Aleppo Codex, winner of the 2014 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish literature, and Pumpkinflowers: A Soldier’s Story of a Forgotten War.

The year 2000 was a pivotal moment for Israel and for the Middle East, specifically the time between spring, when Israel pulled out of South Lebanon, and fall, when the peace process collapsed and the second intifada began. We saw the idea of a peaceful, negotiated settlement to the conflict basically evaporate, the old Israeli left collapse—and it hasn’t been as influential since then—the demise of the kibbutz movement as an important political player and the dawn of a new type of war. Not the sort of war between states, but a very long kind of chaotic war against armed organizations like Hamas and Hezbollah. This period ushered in the birth of a new Israel with few utopian dreams left—a very small and tough little place with different ideas about itself than it had before the year 2000.

I fought in the little guerrilla war in South Lebanon that ended in the spring of 2000 and saw the birth of this new kind of warfare. It was not the Six-Day War; it was not the Yom Kippur War. It didn’t end in six days, or in three weeks as the war in ’73 did. It was a long, drawn-out war with very muddled goals. It didn’t seem to be about land. The enemy didn’t appear to be trying to conquer territory. It was about something else—the enemy was a very ideological, religious, radical Islamist group committed to a fundamentally different idea of the world from that which we understood beforehand. What we encountered in Hezbollah in the 1990s really ended up as being the defining idea of the Middle East post-2000. I remember the hopes people had in the 1990s that peace was nigh and, of course, I miss that hope; I was party to those hopes and I regret their demise.

Israel, since that moment, is in some ways a reduced place. It no longer has those same utopian dreams. People understand that there isn’t going to be a military knockout as we once imagined, there isn’t going to be a 1967 moment and there isn’t going to be some regional signing of a piece of paper that is going to revolutionize Israel’s position in the region and bring about the advent of a new Middle East. None of that is going to happen. It all came crashing down in 2000. But while it’s become increasingly dark on the political front, right now for Israel the outlook on the economic and cultural fronts has become much brighter. It’s interesting that in this way, since 2000, Israel has never been in better shape.