The Capital Pride March is scheduled to start at 4:30 p.m., but by 6:15 p.m. on this humid June Saturday, the only movement is the metaphorical kind. A knot of members and supporters of GLOE—the Kurlander Program for GLBTQ Outreach and Engagement at the Edlavitch DCJCC—are strewn across the grass and street among floats and banners, waiting to begin marching. GLOE is a community organizing force serving DC’s Jewish queer community, so they have ample experience with Pride. “If Pride starts within an hour of its being scheduled, that’s when Moshiach comes,” laughs Charlie, a young man wearing a shiny silver kippah and holding a sign that reads “F*G SAMEACH!”

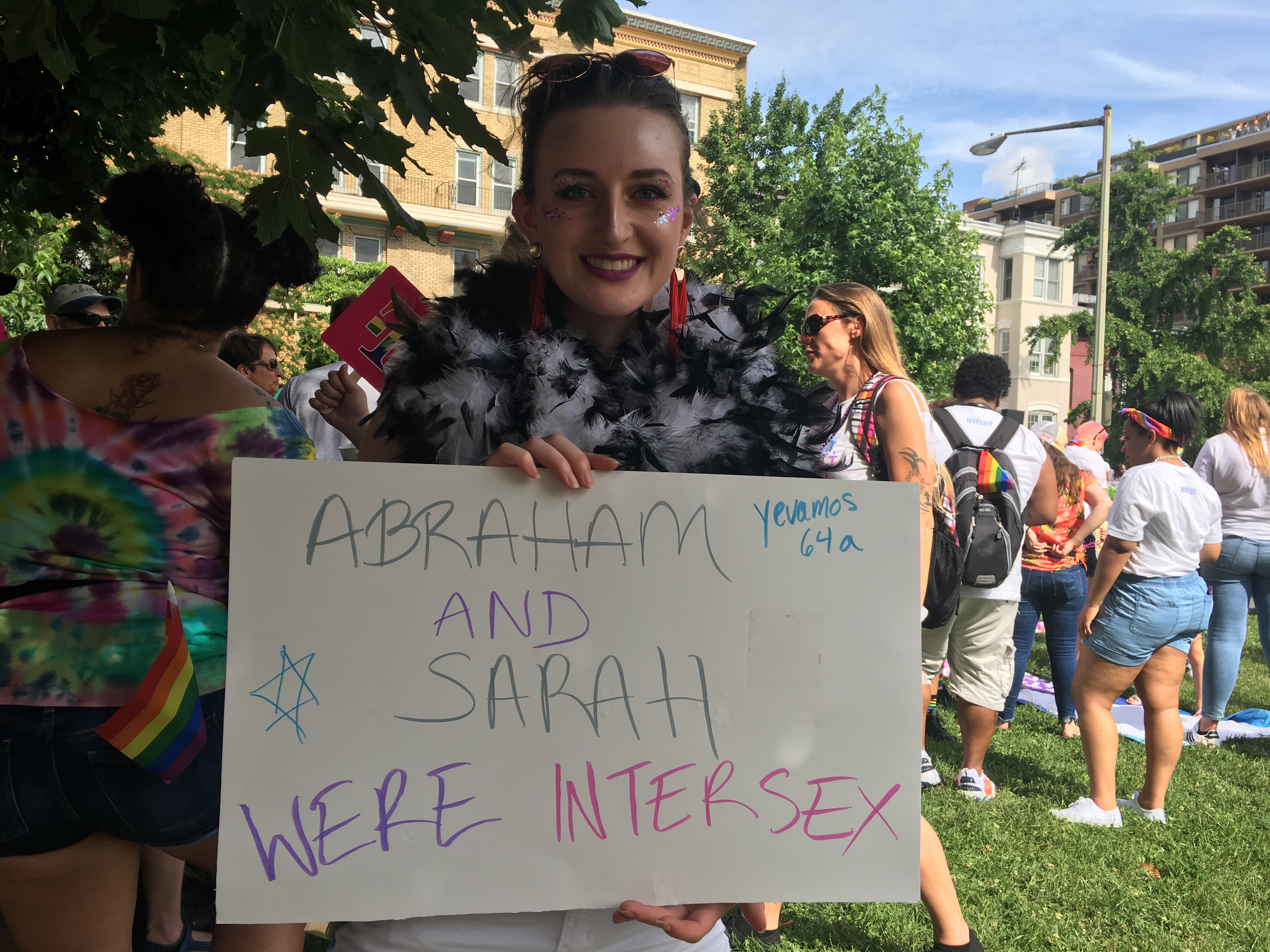

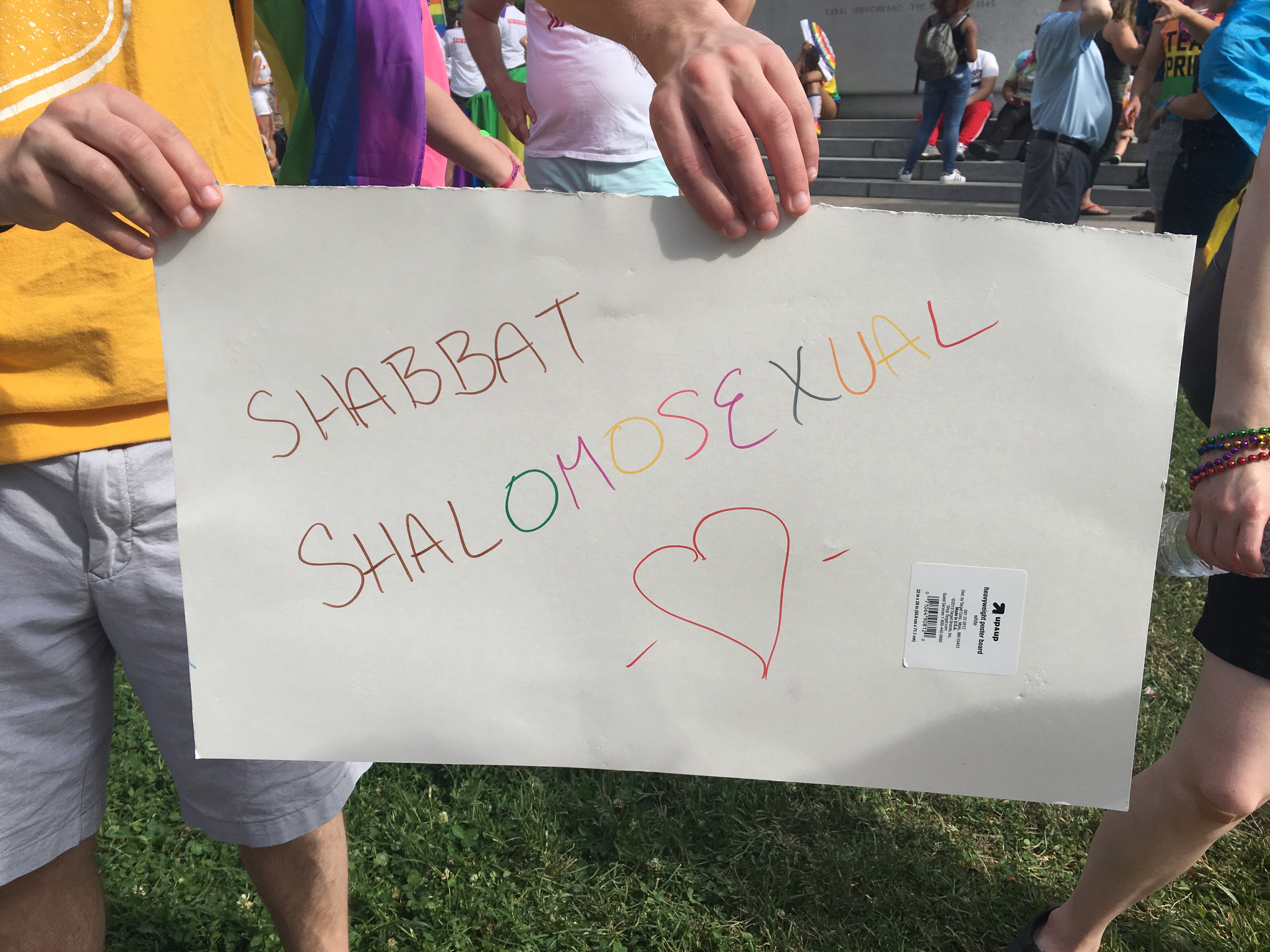

Charlie’s clever crossover sign is one of many—others from the group read “Shabbat Shalomosexual” and “Abraham and Sarah were intersex.” Everybody kibitzes endlessly, passing the time until the parade starts. Even if simply passing connections, these marchers seem completely at home with one another.

“As a non-binary, queer Jew, we’re living our life kind of on the periphery, and navigating our identities on a daily basis,” says Patti Nelson, the secretary of the board of directors of Bet Mishpachah—a DC congregation that serves the LGBTQ community—as well as a GLOE marcher. “And when we are all able to come together in the same space, it feels very safe and welcoming. It’s like I can take a deep breath, because I’m not feeling different parts of me being pushed back and forth.”

Though intersectionality has become a buzzword in the national rhetoric, it is commonly heard in terms of race and gender—Nelson’s context of religion and queerness is more niche. Intersectionality is the concept of cumulative identity, or how different facets of identity interact with one another, both in one’s own experience as well as external perception. These marchers are not just members of the LGBTQ community or members of the tribe. They are uniquely and inextricably both.

Ari Weinstein, program manager of GLOE, agrees that the program’s purpose is to unify these two historically oppressed communities, doubling their efforts toward empathy and equality. “For me, the two [identities] have really grown together, because I see so much of Judaism about just love and compassion, and treating others kindly,” he says. “What I see is the root of all of our Jewish practice and laws and ideas is that you’re treating others how you want to be treated and that you’re treating yourself how you want others to be treated. I think it’s that really important balance of loving others and loving yourself.”

Ben Rosenbaum, marcher and head of the Nice Jewish Boys—a social group for gay Jewish men that often partners with GLOE—says that since these identities already have much in common, they benefit from being taken as interdependent. “The history of Judaism is one of being the other, being the outsider. It’s the ultimate and original queer community,” he says. “So I think that there’s a lot of similarities and a lot of crossover. We have sort of this gift as being queer Jews— of living in a queer community within a queer community.”

Other marchers found new depths in their Judaism by experiencing it alongside their queerness. “I would say that when I came out, I became more Jewish,” says A.J. Campbell, head of Nice Jewish Girls, a social organization for lesbian Jews that also often partners with GLOE. “Embracing your Jewish community and your relationship with God, as who exactly you are—how God made you—that’s the only connection that you can authentically have.”

Andy Anderson, the non-binary marcher who carries the sign about Abraham and Sarah being intersex, agrees that they can now appreciate their Judaism more complexly since interweaving it with their queer identity. “I think that they serve to uplift and form and make more vibrant one another,” they say, wiping glitter out of their face. “I am so excited to be part of social circles and to be part of organizations like GLOE, where I don’t have to leave one part of my identity at home. I believe that I can more fully experience my queerness through a Jewish lens, and more fully experience my Jewishness through a queer lens.”

Anderson says that their Judaism helped them understand the historical nuances of their gender identity. “To have non-binary and gender nonconforming representation in the Torah was really helpful for me to make sense of the fact that non-binary identities weren’t invented within the past ten years,” they said, referencing the fringe theory that Abraham and Sarah’s early infertility mirrors the intersex or trans experience of the disconnect between gender and anatomy. “It’s nice to know that there have always been people like me, there always will be people like me.”

Charlie—the supporter with the silver kippah—had his queerness revive his relationship with religion. “I became Jewish after I came out—I’m a convert,” he said. Although some sects of Judaism are not as tolerant toward LGBTQ identities, he was able to find a community that was. Raised Catholic, he says he often felt as though “you have to be religious and not gay, or be religious and hide yourself,” he said. “No, I’m religious and I love myself, because HaShem made me this way.”

At the heart of the message of intersectionality coming from the GLOE marchers is a sense of solidarity: They refuse to tolerate the closeting of any confluence of identities. “I feel like the liberation of all peoples is bound up within the liberation of one another,” says Gabriel, a GLOE marcher who had first encountered GLOE the night before, at the annual Pride Shabbat service. “I think of what I said this morning at the end of shul, which was Adonai li v’lo ira: God is with me and I won’t fear. And so, when I show up here, even though it’s primarily to support the rights of my community and to advocate for the rights of LGBT people, I also show up as a black man. I also show up as a Jew. I also show up as a feminist—all of these things. And I’m not willing to leave any one of those identities at the door.”

As GLOE marches the 1.5 mile route from Dupont Circle to Logan Square, chants of “Shabbat Shalom!” are heard from the crowd. When the parade stalls, the group dances the hora in the middle of the street. Avid marchers pass out a paper kippahs in a rainbow of colors to confused but grateful onlookers. Over the sirens and cheers, they sing verses from the Israeli-Arabic folk song “Salaam”: Aleinu ve’al kol ha olam, salaam, salaam, salaam (“Upon us and the whole world, peace, peace, peace”).

“I’m very proud of both my gay and Jewish identities,” says Weinstein. “And for me, pride is a really important ritual in and of itself. Just like we have the High Holidays, and we have to take time to take stock of what we could have done better, what we’re grateful for, what we wish for in the coming year, I think it’s a similar type of experience that once a year…” He pauses. “What does it really mean to be proud of who we are? And what does it really mean to be actually not just passive in these identities, but grateful for these identities? I’m grateful to be Jewish and gay. I am proud of what that means. For me, that’s what Pride represents.”