by Leila Miller

Two legacies shape the Anne Frank Center in Buenos Aires, a two-story house-turned-museum in the city’s upscale Belgrano neighborhood. The first is found in a re-creation of the secret upstairs annex where Anne Frank and her family hid for two years during World War II. There’s a replica of the clandestine radio that they listened to, and a red-checkered diary lies open on a desk like the one where Anne wrote.

The second relates to Argentina’s own violent past.

Previously known as “Hilda’s house” after one of its owners, the home offered refuge to leftists during the years of Argentina’s military dictatorship (1976-1983), when as many as 30,000 people disappeared—kidnapped, arrested and executed in secret centers and thrown from airplanes on “death flights.”

“People weren’t hiding there [permanently], but when they knew that there was going to be a raid at their house they would spend the week here,” said the owners’ 23-year-old granddaughter, a tour guide at the museum who requested that her name not be published. “During the dictatorship, it always had its doors open to help people.”

She believes that family history inspired this use of the house: Most of her grandfather’s Polish relatives were killed in the Holocaust. “I think it came a bit from there that they felt that they needed to do something,” she said.

Her family brainstormed options for the house after her grandmother’s death in 2007. Inspired by the book Testimonies for Never Again—From Anne Frank to Our Days (2008), which combines discussion of the dictatorship with Anne Frank’s story and modern-day experiences of youths with social, ethnic, and religious discrimination, her grandfather proposed turning the house into an interdisciplinary museum. A coauthor of the book and a volunteer for the Anne Frank Foundation at the time, Héctor Shalom became the museum’s founding director.

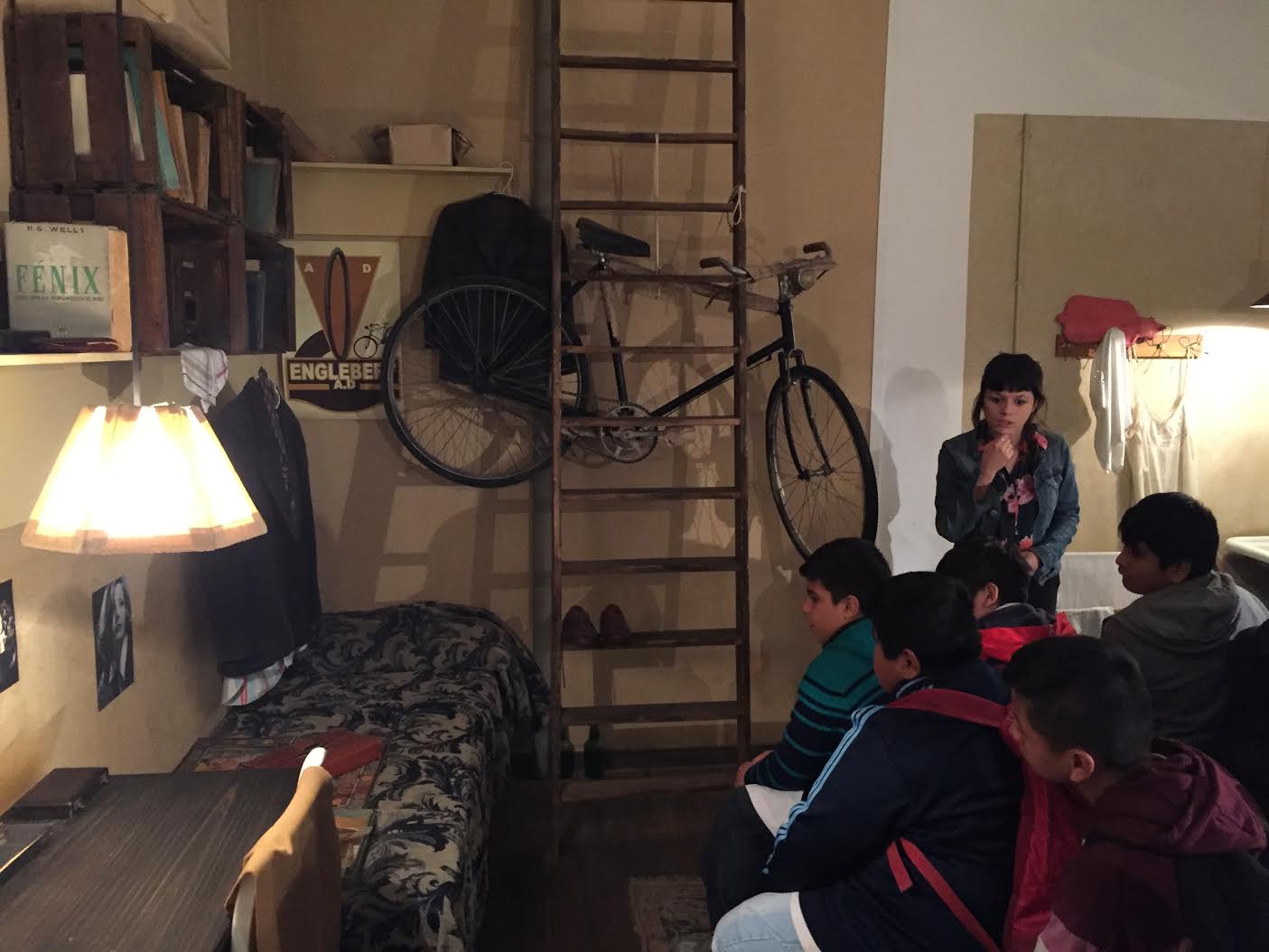

Located on a quiet residential street, the museum, which opened on Anne Frank’s birthday on June 12, 2009 and is affiliated with the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam, teaches both the story of the 15-year-old Jewish writer and the history of Argentina’s dictatorship to over 35,000 visitors a year. A group of 80 high school and college age tour guides—all volunteers—encourages students to connect these tragedies to the present, and to reflect on discrimination, racism and the role of human rights in their own lives.

“The military in Argentina learned from Nazism,” said Shalom. “A museum that works with the memory of something that occurred a long time ago and very far away is more comprehensive if it includes the state terrorism that happened closer to our time. Our guides’ uncles, relatives and grandparents experienced the dictatorship.”

With ties to government agencies, the museum reaches an audience far beyond Argentina’s Jewish community of 220,000—about .5 percent of the country’s population—which is the largest in South America. The Anne Frank Center often partners with the Ministry of Education, which in 2006 established an “Education and Memory” unit that emphasizes teaching the Holocaust and other genocides, as well as the dictatorship and its legacy.

A national law passed in 2013 at the urging of museum officials marks June 12 on the school calendar as a day to teach about social inclusion and discrimination in honor of the young Jewish writer. And in August, Argentine legislator Maria Luisa Storani will propose in Parlasur—the parliament for Mercosur (a bloc of South American countries to promote free trade)— that other countries should to adopt a similar law. “The idea is that these countries will use the figure of Anne Frank to discuss topics relating to the Holocaust,” said Shalom.

During World War II, President Juan Perón prohibited Jewish immigration to Argentina while later permitting Nazis to seek refuge. Jews constituted just 1 percent of the total population during the military dictatorship, but accounted for 5 to 6 percent of the disappeared—between 1,500 and 1,800 people.

Today, there are about 10 kosher restaurants, 50 synagogues and 35 Jewish schools in Buenos Aires. The Buenos Aires Holocaust Museum features an exhibit on Adolf Eichmann’s capture in Argentina, the nonprofit Generations of the Shoah sponsors literary workshops for Holocaust survivors and the organization Zikaron BaSalon hosts meetings for survivors to tell their stories in an intimate, living-room setting.

But the Anne Frank Center uniquely combines Holocaust education and Argentinian history. The tour starts on the first floor, where students learn about the rise of Nazism and the Franks in a room filled with photographs—on one wall, a smiling Anne Frank poses with her sister Margot, and just above it, there is a snapshot of a Nazi motorcade. From there, visitors go upstairs, where a wall-sized photograph presents a bird’s-eye-view of the Anne Frank House and its neighborhood in modern-day Amsterdam. Around a corner, a movable wooden bookcase conceals the entrance to the Secret Annex.

“You are at the age where you’re developing your identity,” Marcela Céspedes, a 15-year-old guide, told a group of seventh-graders crowded into a model of Anne Frank’s bedroom, who were visiting on a Tuesday in late June. She pointed to the many photographs of movie stars and landscapes stuck to the walls, adding, “We can see all of [Anne’s] adolescence.”

Presenting an exhibit on the Argentine dictatorship, Julieta Menendez, 17, a guide and student at the highly selective Escuela Carlos Pellegrini, asked students to distinguish between photos of book burnings in Córdoba during the dictatorship and in Berlin during World War II. In Argentina, “people were persecuted for their beliefs,” she told the class.

Besides giving tours, the museum also sponsors literary contests, seminars and other projects to honor Anne Frank and her desire to write. In a ceremony in late June at the auditorium of the Soka Gakkai International Cultural Center in Buenos Aires, the museum celebrated a project where over 1,500 students from 44 mostly non-Jewish schools from Buenos Aires and its neighboring provinces created newspapers featuring research on the Holocaust, the dictatorship and other examples of discrimination.

“Respecting the difference of others, discrimination, the acceptance of people as human beings— these are some of the topics that are very clear in her diary,” said Georgina Zaragoza, a sixth- grade teacher at the Escuela Cultural Armenia in Lanús, a city in Buenos Aires Province, who incorporated the Armenian genocide into the newspaper.

Diego Aszenberg, a 24-year-old tour guide who studies literature at the University of Buenos Aires, carries crumpled-up slips of paper in his pocket with quotes from Anne Frank’s diary. While her story ended in tragedy, he tries using her words to motivate students.

“I tell them about their protectors, who would bring them magazines so they wouldn’t feel abandoned,” he said. “I tell them that Ana didn’t fill herself with hate but searched for hope in life… The museum’s message is that you can be a protector.”

3 thoughts on “In Buenos Aires, an Anne Frank House With Its Own History”

Thank you for this excellent article!

Very interesting! I did not know of that cultural space in Buenos Aires!!! Thank you for the enlightening!

This museum should be better known to US tourists visiting Buenos Aires! Especially for Jewish families traveling with kids, so kids can make connections between what they learned about the Holocaust and Argentine history. The years of the last dictatorship have been a key period in Argentina, many people abroad have heard of the disappeared but not much more, so this is a great way to learn about it. A visit to the former clandestine detention center ESMA is revealing too.