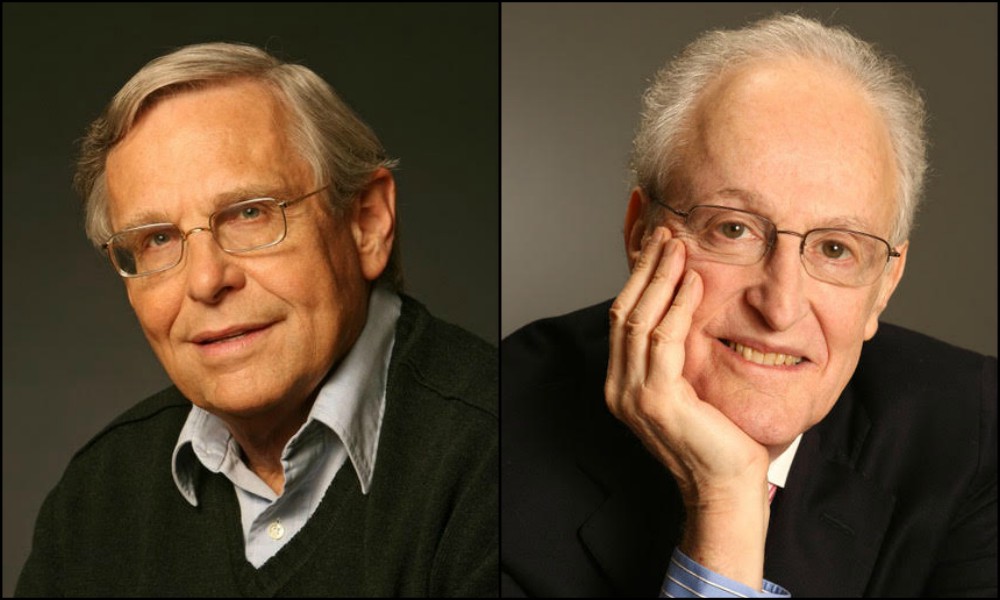

Broadway Songwriting Team Celebrate 65 Years of Creative Friendship

“In the theater you are either Jewish, Italian or gay and I chose Jewish,” says Protestant-born lyricist Richard Maltby Jr. during a conference call that includes his long time Jewish collaborator, composer David Shire. “Musical theater is so profoundly Jewish—it’s like living in a Kibbutz—you can’t help becoming Jewish. Also, my wife is Jewish, my children are Jewish and we belong to a temple.”

To what degree his self-description has been employed before to comic effect is arguable, though Shire laughs appreciatively as if hearing it for the first time. Theirs is an artistic partnership that has lasted 65 years, producing such works as Baby (seven Tony nominations including Best Musical and Best Score), Closer Than Ever (Outer Critics Circle Award for Best Musical), Big (Tony nomination for Best Score) and Starting Here, Starting Now (Grammy nomination for Best Cast Album). Indeed, they’ve enjoyed one of the longest runs (if not the longest) as a theater team in Broadway/off-Broadway history. Each artist has also had distinguished individual careers writing film songs and scores. Shire is an Oscar and Grammy winner and Emmy nominee whose songs have been recorded by Barbra Streisand, Melissa Manchester, Glenn Campbell and Johnny Mathis; Maltby conceived and directed two Tony Award-winning musicals, Ain’t Misbehavin’ and Fosse, among other credits.

And, on Monday, March 9, to honor their artistic accomplishments, The Bistro Awards will endow them with a Bob Harrington Lifetime Achievement Award at its 35th annual gala held at The Gotham Comedy Club. The Bistros, the oldest awards of its kind in the industry, recognizes and nurtures cabaret artists. “Along with their theater credits, Maltby and Shire’s songs are consistently performed by cabaret artists in cabaret venues throughout the country,” says Sherry Eaker who has served as the Bistro Awards’ producer since its inception. “And cabaret was their launching pad for more than one production.”

So here’s a little back story: Their friendship did not get off to an auspicious start. They first met as undergraduates at Yale in 1955 when they were introduced through a mutual classmate who lived in Shire’s dorm and knew the latter was looking for a lyricist.

“It was a Shidduch,” Shire recalls.

While the two joined forces to write for Yale’s Dramat (the school’s undergraduate theater), initially they had an intense dislike for one another.

“David was a complete hick from Buffalo,” says Maltby. “And I was a pretentious shit from Long Island.”

“He was theater-wise and I was theater-stupid,” adds Shire. “I brought into the senior show audition 12 sheets of music I had written. No book, no lyrics. I felt all you needed was a ballad, a few romantic tunes and the inevitable rumba. Their jaws dropped. Richard taught me how to write theater songs as opposed to cocktail tunes.”

Oddly enough, through the teaching process, Maltby says he too learned how to write musical theater songs. And there was no shortage of great mentoring examples on Broadway: West Side Story, My Fair Lady and The Most Happy Fella. “We’d leave New Haven in the morning, take the train into New York, see a matinee and be back in the evening,” he recalls. “It was wonderful.”

After serving a six-month stint in the National Guard Reserves (it was the Vietnam era) the songwriting team moved to New York and within short order made their off-Broadway debut with The Sap of Life (1961) at the Sheridan Square Playhouse. Stephen Sondheim, Jerome Robbins and Leonard Bernstein took notice. Right from the get go they were recognized as up and comers.

Asked if it was easier to kick off a musical theater career in the early 1960s, they say this: On the one hand, it was virtually impossible to get heard back then unless you were established. But if you were among the fortunate few (very few) to find a producer who would listen, you might get produced on Broadway or off-Broadway. Today, on the other hand, while there are many places to present your work—like readings and workshops—it’s never been harder to land a Broadway or even off-Broadway production, not least because of the exorbitant expense. “It costs $2 million to put on an off-Broadway show,” notes Maltby. “We did our first show for $25,000.”

Like many collaborative processes, theirs is idiosyncratic and hard to define, though generally, it seems the music takes precedence and is the force shaping their work.

“David’s music offers unexpected surprises and therefore it’s up to me to find a language that fits, that’s original and exciting,” says Maltby. “I always feel the lyric is inside the music.”

“But Richard may give me a title or a first line just to get me started,” says Shire.

“He free-associates and out comes the melody,” says Maltby. “In the collaborative process, there’s a lot of reciprocation. We’re often asked how we’ve managed to stay friends for so many decades. The answer is, we never say, ‘It has to be my way.’”

When I wonder how or even if cultural/personal heritage molds talent and artistic sensibility, both Maltby and Shire have little doubt that they play their role. After all, Shire’s father was a piano teacher and bandleader and Shire grew up listening to his father teaching the great theater songs—from Gershwin to Kern to Rodgers and Cole Porter. He came on board with “a vast harmonic vocabulary that ultimately exploded,” says Maltby.

Maltby’s dad was also a bandleader, a recording artist at RCA and a “fabulous musical arranger who arranged music with astonishing mathematical precision,” he continues. “And I believe that’s where I get my skills for structured storytelling.”

Their narrative hallmark, they agree, is recounting the lives of ordinary people—parents and children, fathers, mothers, families. What infuses their songs is universal experience. Still, their characters are white bread, Shire admits. Their show Baby, for example, exploring how facing the birth of a child can unwittingly put a relationship in focus and/or in crisis, zeroes in on three white couples. In a later production, in an effort to bring the show into the late 20th century, they made one of the couples interracial. More recently producers have insisted they make one of the couples gay.

“We’re wrestling with that,” says Shire. “It’s a little trickier.”

At the moment, they are reworking several older productions from various angles—narrative, character and yes, political correctness. Their musical version of Wycherley’s restoration comedy, “The Country Wife,” for example, is set in New Orleans in the second half of the 19th century, “where blacks in Creole society were just as aristocratic as whites,” says Shire. “Originally this show’s humor was grounded in seduction. That might be a problem now. Richard found a way to get around it by putting it in the context of its era and making it clear we’re seeing it through the eyes of the #MeToo movement.”

They are cautiously optimistic about the future of musicals—citing Pasek & Paul, Lin Manuel Miranda, David Yazbek and Sara Bareilles as the new crop they admire—and hope aspiring artists will not get discouraged. Despite the obstacles, greater opportunities exist now to express oneself in theater thanks to the wide range of musical genres on stage—from rock scores to electronic scores to the single piano. And theater writers/composers come from an array of backgrounds. Think Elton John (Aida) or Paul Simon (Capeman). Regardless, the goal is always to get out there and be heard, they reiterate.

“Get it seen, do it anywhere,” Maltby urges. “Your peers will be your mainstays, not established people.”

Simi Horwitz is an award-winning arts reporter and film reviewer who recently won a first-place Simon Rockower Award for her piece “Abby Stein: A Gender Transition Through a Jewish Lens,” published by Moment Magazine.