Bob Dylan On The Roof

It was at summer camp in northern Wisconsin in 1953 that I first met Bobby Zimmerman from Hibbing. He was 12 years old and he had a guitar. He would go around telling everybody that he was going to be a rock-and-roll star. I was 11 and I believed him.

Even at that tender age, I could see that most of the other kids weren’t really buying it. None of them would say so to his face, but I could hear them making comments and laughing behind his back, and it bugged me. Why didn’t they see what I saw? Maybe I was the most gullible kid at Herzl Camp, or maybe it was the beginning of a beautiful friendship. Maybe a little bit of both.

Ultimately, of course, it didn’t matter whether the other kids bought into Bobby’s dream, or whether I did. The only thing that mattered was that Bobby believed in it. And that’s why it came true.

Don’t get me wrong. Bobby was very popular with the other kids, especially the girls. This was due in part to his natural charm, but also to his talent. He was not just the kid with the guitar—he could play the thing. He was a maverick and a freethinker, always fun to be with, challenging, and sometimes very disruptive.

When the counselors came up with a good idea for an activity, Bobby came up with a better one. He was a prankster who liked to stir things up. Add to that a hip, edgy sense of humor and a surprisingly well-honed ability to be provocative, and that was Bobby. He always knew when a dose of sarcasm was called for, or when a little bit of ruckus was needed—and I was down with all of it. Bobby was my kind of guy!

Bobby and I teamed up with a third kid in our cabin, Larry Kegan, who, like Bobby, was talented and deeply into music. He was also a natural-born hell-raiser. Larry was fun and passionate, but, as the boxing champ at Herzl, I was the protector of our little band.

I’d been well prepared for the role by my father, Abe, an old Golden Glover who handed me my first pair of gloves in our backyard when I was nine and said, “Put these on. I’m going to teach you to box.” When I’d done as I was told, he said, “OK, now put your hands up. Ready?”

“Yes…” I managed, and then—BOOM—he hit me in the kisser so hard he knocked me down.

“Why’d you do that?” I whined, looking up at him.

“So nobody else ever will,” he said.

Our lessons continued from there, covering the techniques, skills, and style of boxing. He taught me how to coordinate my feet and hands, dance around my opponent, and use a straight left jab to set up a powerful right. I picked it all up naturally and it turned out I was pretty strong and pretty fast on my feet. If Muhammad Ali could float like a butterfly and sting like a bee, Louie Kemp could dance like Michael Jackson and hit like a frozen mackerel.

After about a year of training, Dad told me I was ready to protect myself. “I don’t ever want to see you start a fight,” he told me, “but if anybody starts up with you, show them what you can do. And I want you to carry on the family tradition of sticking up for the little guy against any bully who comes along.”

“OK, Dad,” I said. And that’s exactly what I’ve done ever since.

Maybe you’re getting an inkling of why the three of us were every counselor’s worst nightmare—not quite juvenile delinquents, but close enough—and proud of it.

One night, Bobby, Larry and I were feeling kind of restless; we couldn’t sleep. So, we started hatching a plan for dealing with our archenemies, the kids in the next cabin. In our not-so-humble opinion, these kids were just too perfect. They never broke the rules, never got into any kind of trouble. Something had to be done about them.

After hours of plotting, scheming and bullshitting, we decided on a clandestine, nighttime attack on the enemy cabin. It’s easy to see now that this wasn’t a very sophisticated or well-thought-out effort, but it seemed like a great idea at the time.

In the dead of the night, we made our move. Armed with nothing but three cans of the counselor’s pilfered shaving cream, we sneaked into the enemy cabin, where the forces of good all appeared to be sleeping. We crept stealthily from bunk to bunk, discharging dollops of shaving cream upon the heads of the entire horde. The only hard part for me was trying not to burst into peals of laughter every time I stole a glance at Bobby. He was very meticulous about his shaving cream placement, and quite artistic in his designs—the natural-born van Gogh of Barbasol. The objects of our efforts slept through the whole thing.

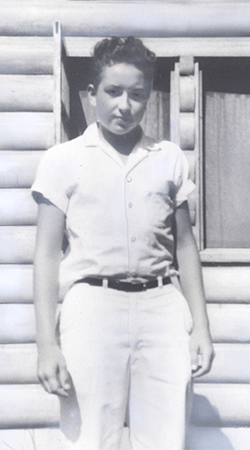

Young Bob Dylan at camp, 1956

Having completed our mission, we split as fast as hell back to our cabin, jumped into our bunks, and composed ourselves as best we could into the image of three innocent kids lost in dreamland.

Of course it wasn’t long before our whole bunk was jolted awake by the sound of shouting and the flicker of flashlights outside our screened windows. Sure enough, dark figures were headed in our direction. We three knuckleheads went back to feigning sleep, praying that the Angel of Death would pass over our cabin.

This, alas, was not to be. The shaving cream had barely dried on the foreheads of our whiny little foes when the counselors made a beeline for the likely culprits: us.

As our bunkmates looked on silently, our captors marched us out of the cabin and along a dirt road that led into the woods. When I finally got up the nerve to steal a glance at Bobby, I could see that his signature smirk was intact. That cheered me up a little, in spite of the cold and the mosquitos the size of silver dollars that kept dive-bombing us.

When we’d gone on for what seemed like miles (but was probably just a few hundred yards), the counselors told us to sit down on some logs, and they started building a bonfire. Were they planning to burn us at the stake? As they were busy gathering up kindling, the three of us looked at each other…we weren’t taking any chances. Without exchanging a word, we took off into the darkness like three little Jewish bats out of hell.

It wasn’t long before we came upon one of the counselors’ cars parked by the side of the road. The Lord was with us; the keys were in the ignition. Without giving it a second thought, I slid behind the wheel, Bobby jumped into shotgun position, and Larry—always the jock—vaulted into the backseat just as I gunned her out of there in a cloud of dust. I had to be the best eleven-year-old wheelman in the state.

“Stop…STOP! You little monsters, get back here!” was all we could hear as the counselors—probably not more than teens themselves—got smaller and smaller in the rearview. Bobby was laughing, which made me laugh, which in turn made Larry laugh.

Larry had a beautiful laugh; it almost sounded like he was singing.

Herzl Camp disappeared in an instant, and we found ourselves on a dark stretch of deserted highway. The laughter sputtered out, and Larry and I exchanged worried glances in the rearview as I slowed the car to 30 and tried to think. Was it possible that our little shaving-cream raid had somehow transformed itself into Grand Theft Auto? I stole a glimpse at Bobby and found him looking straight ahead with a determined expression on his face that seemed to say, Let’s keep driving forever.

Eventually, of course, we turned back to face the music and found ourselves in front of a very angry rabbi who threatened to send us home the next day. Luckily for us, he was one of those rare, generous souls who believe in second chances…sometimes even third chances. In retrospect, I am very glad he didn’t make good on his threat, as it would have deprived me of some of my fondest memories of childhood.

Many years later, when the subject came up, Bob summed up that riotous summer with a rhetorical question: “Can you imagine,” he mused, “if there had been 400 campers like the three of us?”

The following summer, back at Herzl with my pals, I witnessed an event that could vie for a legit place in American musical history: the 1954 version of the camp’s “talent night.” It was, to the best of my knowledge, the first public performance by the prototypical Bob Dylan.

Quite often over that summer, I’d joined small groups of kids in the activities room as they’d gather around Bobby to listen to him play his guitar or pound the keys of the old piano and sing Jerry Lee Lewis-style. Some days, he’d play some Little Richard. But “talent night” was special. It was the night when the entire camp—more than 400 kids, plus rabbis, counselors and staff—would assemble to witness the best skits, magic acts and musical numbers we could muster. It would be Bobby’s largest and most attentive audience to date. Perhaps it would provide a hint of what the future held.

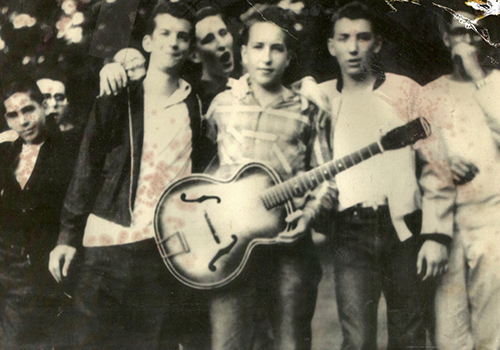

Bob Dylan & Louie at Herzl Camp, 1957

Bobby and Larry had decided to perform together, with Bobby on piano. As they looked out at a sea of camp whites, their all-black outfits provided a sharp, rather sinister contrast. There was also some question about the appropriateness of the song they’d selected. Was it really suitable to sing a hard-driving blues number for kids as young as eight or nine? I, of course, loved it.

The tune was called “Annie,” and included lyrics as follows:

Annie had a baby, can’t work no more

Annie talks to the baby instead of me

Annie walks with the baby instead of me

Annie sleeps with the baby instead of me…

It wasn’t exactly “Kumbaya.” When confronted about his choice of material, Bobby responded tersely and typically: “They’re squares,” he said. In any case, the boy who would be Dylan had made his debut, and—trust me on this—he’d nailed it.

Another performance I remember fondly took place on a warm afternoon a few summers later, in 1957. This was the traditional day when the campers took on the roles of the counselors. The idea was to teach us responsibility, leadership and cooperation—all qualities that my two friends and I generally lacked. Bobby took the place of Shlomo, the music director. Though he’d often beaten the poor old piano to death with impromptu performances inside the activities room, Bobby had never played his guitar on top of the building. Now, seven years before Fiddler on the Roof would open on Broadway, he proceeded to do just that.

All day long, silhouetted against the sun, Bobby played every rock and blues song anybody had ever heard of, and lots that we hadn’t. Larry and I kept him supplied with water and requests as, all day long, kids would stop by to listen in the courtyard below. Seeing Bobby on the roof in full performance mode, like a maestro at Carnegie Hall, convinced me that nothing could, would or should ever stop him. He was our fiddler on the roof and would become the indelible image of the last days of our childhood.

Bobby didn’t look anything like the vapidly handsome blond pop stars of the day; he looked like a skinny little Jewish kid who’d never be anybody’s bet to conquer the world. But that’s exactly what he would do.

Excerpted from Dylan & Me: 50 Years of Adventures, by Louie Kemp with Kinky Friedman (WestRose Publishing). Available for pre-order on www.dylanandme.com, and on Amazon beginning June 12.

4 thoughts on “Bob Dylan On The Roof”

What pranksters and so endearing. For someone who continues to study Bobby Zimmerman’s life and music, this book with fill out his life for me. Another side of the great bard. Thank you.

Great stories, and well written. Thanks a bunch for sharing your recollections of Bob when he was just a kid like the rest of us – and not.

Can’t wait to read more!

yasher koach, Reb Louie…may it always be with strength…

STEPHAN PICKERING / חפץ ח”ם בן אברהם

Torah אלילה Yehu’di Apikores / Philologia Kabbalistica Speculativa Researcher

לחיות זמן רב ולשגשג…לעולם לא עוד

THE KABBALAH FRACTALS PROJECT

לעולם לא אשכח

IN PROGRESS: Shabtai Zisel ben Avraham v’Rachel Riva:

davening in the musematic dark

I was also at Herzl Camp the summer of 1957 and have a photo of Bobby and me. I was from Sioux City, Iowa and was at Herzl with lots of friends