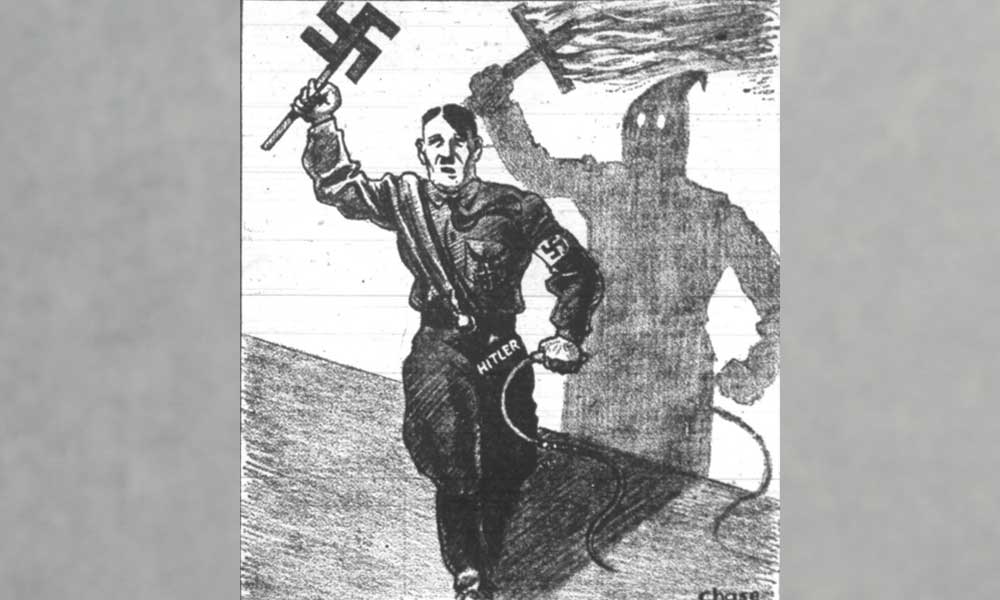

On April 8, 1933, the Journal and Guide of Norfolk, VA, a Black-owned weekly newspaper, ran a cartoon depicting Adolf Hitler in his customary Nazi uniform complete with swastika armband, brandishing a whip in one hand and holding up a swastika on a short pole with the other. Cast against the wall behind is a looming shadow: a hooded KKK figure clutching the same whip but holding up a burning cross instead of a swastika. “Another Klansman,” reads the caption above.

Hitler had been chancellor of Germany for only 68 days at that point, but Black publishers and editors like those at the Journal and Guide, The Chicago Defender, New York Amsterdam News and the Pittsburgh Courier were already drawing attention to the plight of the Jews in Germany. In fact, although most Black newspapers of that time were weeklies with small editorial staffs and limited financial resources, the Black press would go on to call out Nazi oppression of Jews, publishing hundreds of anti-Nazi cartoons, articles, commentaries and editorials throughout the 1930s and into the 1940s. These papers stood out in contrast to mainstream publications. Even The New York Times, then as now the nation’s most prominent newspaper, handled Nazi antisemitism with a soft touch. As recounted in Laurel Leff’s 2005 book Buried by the Times, the paper’s publisher Arthur Hays Sulzberger, himself Jewish, did not want the Times to be identified as stridently “Jewish” and thereby lose prestige.

The “Another Klansman” cartoon communicated an instantly recognizable message to the Journal and Guide’s readership: Black Americans and German Jews were facing common enemies. Indeed, this little-known chapter of Black-Jewish relations came about because Black America and its newspapers already possessed a sharpened sense of what oppression looked like. Hitler’s hatred of anyone “non-Aryan” was not lost on Black Americans and the Black press. “What was happening to Jews in Europe was very similar to the kind of Jim Crow segregation that Black people were experiencing here in the United States,” says Matthew Delmont, a professor of African-American history at Dartmouth and author of Black Quotidian: Everyday History in African-American Newspapers. “The violence against Jews was seen as similar to lynching.’’

Black solidarity with Jews was also a natural outgrowth of the deep respect Black Christians held for the Hebrew Bible, in particular the Book of Exodus, and to the desperate mutual search for allies. “Racism tied the United States and Germany together more than anyone wanted to admit at the time, except for Black newspapers,” says Eric K. Ward, a veteran civil rights activist and executive vice president of Race Forward, a nonprofit devoted to advancing racial justice. “They understood that fighting racism anywhere strengthened the fight against racism everywhere. The Black press at that time, we forget, saw antisemitism and anti-Black racism as part of the same system—a system built to divide, to dehumanize and to justify violence in the name of power.”

The 1930s: A Grim Decade

Like Jewish newspapers, which also served a community with a long history of enduring ostracism, bigotry and isolation, papers aimed at Black readers focused on news and issues that impacted them. Black papers had existed at least since 1827 when Freedom’s Journal appeared in New York, and in 1847, Frederick Douglass famously launched The North Star to advocate for racial equality and the abolition of slavery.

At the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, almost every American city of any size had a Black-owned newspaper, sometimes more than one. They published the works of distinguished Black authors, including Richard Wright, Gwendolyn Brooks and Langston Hughes, and gave space to major national and international news, focusing on implications for the Black community at large. They also were a place to view the passing parade of everyday life: weddings, obituaries, church sermons, bowling leagues. “During the 1920s and ’30s, when major papers virtually ignored Black America, the glory days of the Black press began,” playwright and former reporter Larry Muhammad wrote in a 2003 issue of Nieman Reports.

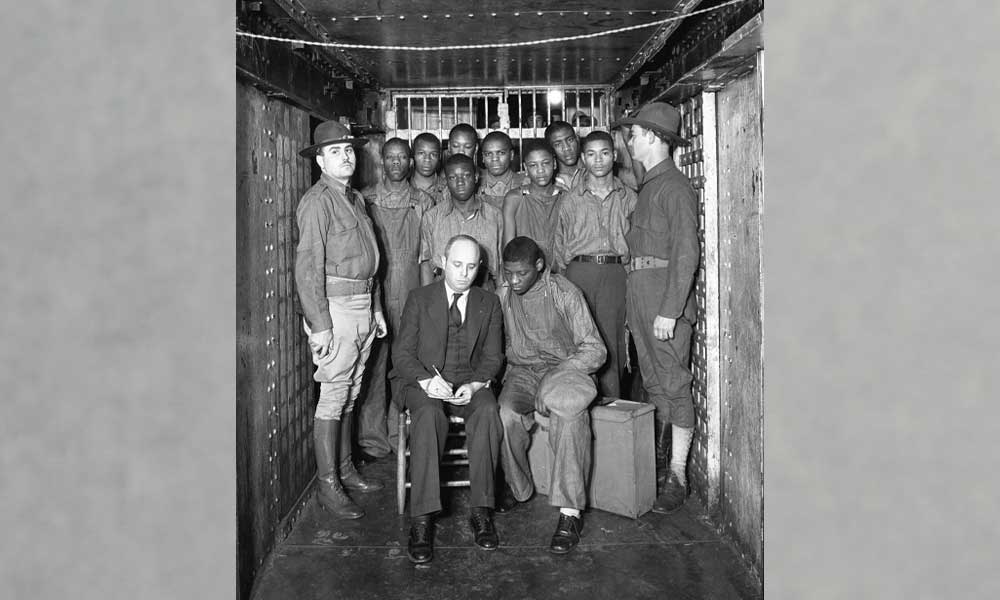

The Scottsboro Boys with lawyer Samuel Leibowitz. (Photo credit: Morgan County Archives Decatur, Alabama)

Some 70 years after emancipation, the 1930s were still a grim time for Black Americans. The decade opened with the case of the Scottsboro Boys—nine Black teenagers hauled off a freight car near Scottsboro, AL, in 1931 and falsely accused of raping two white women. The case became a cause célèbre in the Black press, with the Journal and Guide providing on-the-scene, day-to-day coverage of the trial. With segregation and bigotry prevailing in the South and elsewhere in the nation, the Black press served as a kind of Greek chorus for airing reports of injustice and brutality in the decades before civil rights laws were enacted. “Mississippi Man Lynched While Jury Weighs Fate,” ran the headline on the front page of the New York Amsterdam News (also known as the Amsterdam News) on September 21, 1935, for example.

The horrific acts of white mobs seizing Black Americans and hanging them (or burning them, in some cases) had been in decline since the post-Reconstruction era of the late 19th century, but even so, according to Tuskegee University (formerly the Tuskegee Institute), there were 119 recorded lynchings of Blacks in the decade of the 1930s, mostly in the South. And the actual numbers were likely higher.

Racism and the economic misery of the Great Depression drove increasing numbers of impoverished southern Blacks to northern cities, where they found opportunity woven into a new fabric of ghetto confinement, poverty and second-class citizenship. The illiteracy gap was wide: 3 percent of whites over the age of 14 couldn’t read or write in 1930 compared to 16.4 percent of Black Americans. This was no surprise, since the educational system served them poorly: In 1930, it had been 34 years since the U.S. Supreme Court decided Plessy v. Ferguson, creating the racial divide of “separate but equal.” (It would be another 24 years before the Supreme Court overturned it in Brown v. Board of Education, and ten more before Congress would approve the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964, effectively ending legal segregation.)

Of course, there were bright spots amid the grimness. The Black press proudly followed the doings of the group of prominent Black Americans who formed President Roosevelt’s unofficial “Black cabinet.” Apart from FDR’s official and all-white cabinet, the alternative one comprised a kind of brain trust for Roosevelt on New Deal legislation as it affected Black citizens. The Black cabinet advocated, with mixed results, for greater opportunities for Black Americans in federal efforts such as the Works Progress Administration (helping the unemployed) and the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (helping poor farmers). Among them was Ralph Bunche, a young political science professor at Howard University, who would earn the Nobel Peace Prize in 1950 for his work as a UN administrator negotiating an armistice between Egypt and the fledgling nation of Israel.

- Linotype operators of The Chicago Defender, 1941 (Photo credit: LOC)

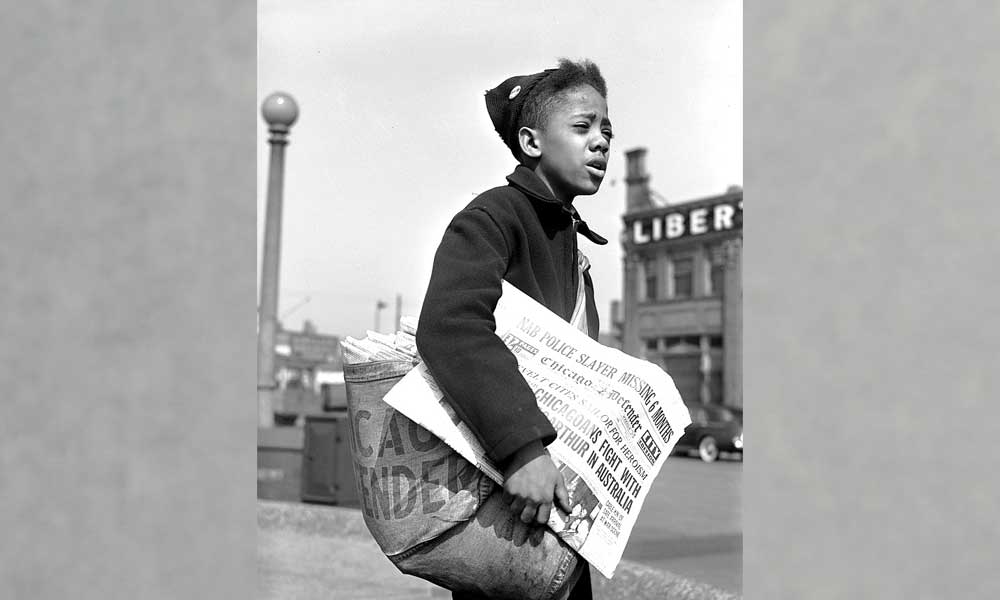

- Newsboy selling The Chicago Defender, 1942 (Photo credit: LOC)

- The Pittsburgh Courier, 1941 (Photo credit: LOC)

The Black press also covered hopeful progress in sports and the arts, two areas that brought Black Americans into partnerships with their Jewish counterparts. Jewish jazz greats Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw were among the first to lead racially integrated bands in the 1930s. Composer George Gershwin was influenced by Dixieland Jazz and Harlem stride piano in writing many of his best-known works, including “Rhapsody in Blue.”

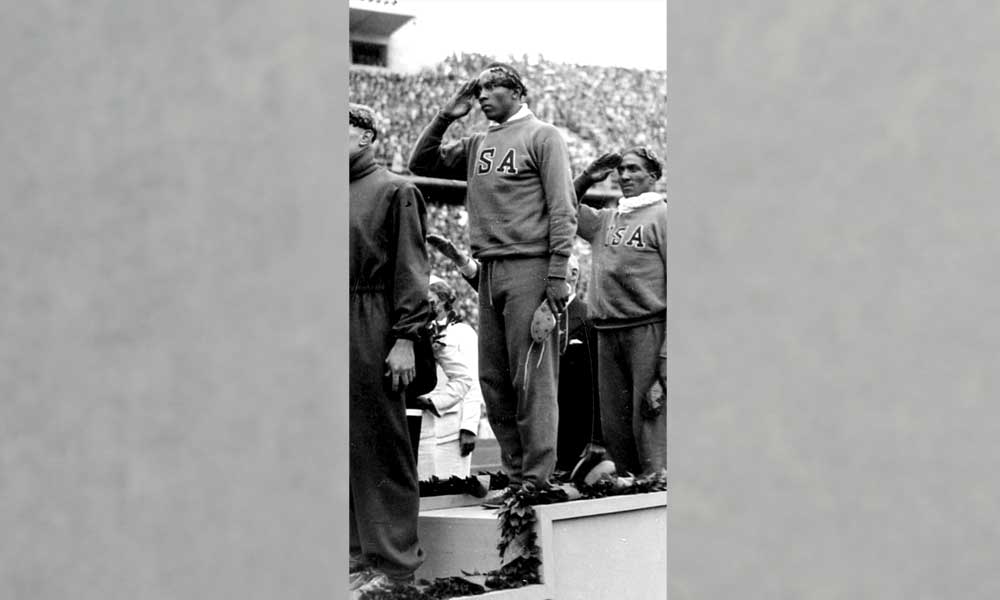

In sports, there was much discussion in the Black press over the 1936 summer Olympics in Berlin, at which Jesse Owens would famously win four gold medals in track-and-field events. Owens and another Black competitor, Ralph Metcalfe, were last-minute replacements for two scheduled U.S. runners in the 400-meter relay, Marty Glickman and Sam Stoller—both Jewish. Rounds of finger-pointing ensued, but the historical bottom line placed responsibility for the switch on track coach Dean Cromwell and U.S. Olympic chairman Avery Bundage, who were accused of caving to Hitler’s hatred of Jews. On June 6, 1936, about two months before the August games, The Chicago Defender published an eloquent letter by Charles W. Harris of New York City protesting the participation of “some of our Negro brethren in the upcoming Olympic Games to be held in Germany.” His opposition was due to his admiration of a “great Jew, by the name of Julius Rosenwald…who built schools throughout the South to educate Black youth.” Harris went on to say: “The Jews are being mercilessly persecuted in Germany, and for our boys to be engaged in the coming Olympics is an endorsement of Nazism.”

Jesse Owens at the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, Germany. (Photo credit: National Archives and Records Administration)

Despite these reservations, Owens’ victories became a huge propaganda win for Hitler’s foes, flying in the face of the Nazi belief of “Aryan” superiority over Blacks, Jews and other “inferior” races, and was heralded by both Blacks and Jews. The Black-owned Los Angeles Sentinel reported after the games ended that Eddie Cantor, the famous Jewish comedian and singer, wanted to get Owens to sign a Hollywood contract. “Owens’ victory and his conduct at Berlin when Hitler tried to snub him mark him as an outstanding character, and I believe that Jews the world over owe him a debt of gratitude,” Cantor told the Sentinel in a story dated August 20, 1936.

Looking through the pages of Black newspapers in the 1930s, it is impossible to ignore the variety of attitudes toward Jews. At times, editorials and letters lapsed into language that bordered on antisemitism, or Jewish stereotyping at a minimum. Atlanta Daily World columnist William A. Fowlkes wrote on November 20, 1938, in the wake of Kristallnacht, that Black American leaders who promoted increased wealth as the key to overcoming bigotry (“The dollar shall make you free”) were misguided. “Ever since the Jews wandered around in the wilderness on their way from enslavement to the promised land, their leaders have taught them to beat the Gentiles to the economic draw,” Fowlkes wrote. The lesson for Black Americans, he said, is that “Money has not proved security for the Jews, though it has given them temporary power, prestige and strength.”

Of course, like other newspapers, Black papers were businesses, supported by advertising revenue. And so their pages were full of ads for funeral homes, grocery stores, pharmacies, insurance brokers, lawyers and the like, and they often urged readers to patronize Black advertisers. (The Colored Merchants Association, founded in 1928, launched a marketing campaign telling Black consumers to “Buy Where You Can Work” or “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work.”) Occasionally, ad revenue came from unlikely sources. In 1929, numbers-game racketeer Stephanie St. Clair (alias “Queenie”) took out an ad in the Amsterdam News to tell prospective male suitors flooding her with letters and phone messages that she was “not looking for a husband or a sweetheart.” And since publishers were in the business of selling papers, editors were likewise not adverse to sensationalized stories and splashy headlines. “Cheating Wife Is Killed by Enraged Husband Who Comes Home Too Soon,” was one example from the Journal and Guide in 1933. Another one, from the Philadelphia Tribune on October 18, 1941, seemed prophetic: “Holocaust razes town; 125 homeless.” But the story was about a wind-whipped fire that destroyed 29 homes in nearby Salem, NJ. The term “Holocaust” wouldn’t be used to describe the mass murder of Jews by the Nazis for another decade.

Influential Black Publishers

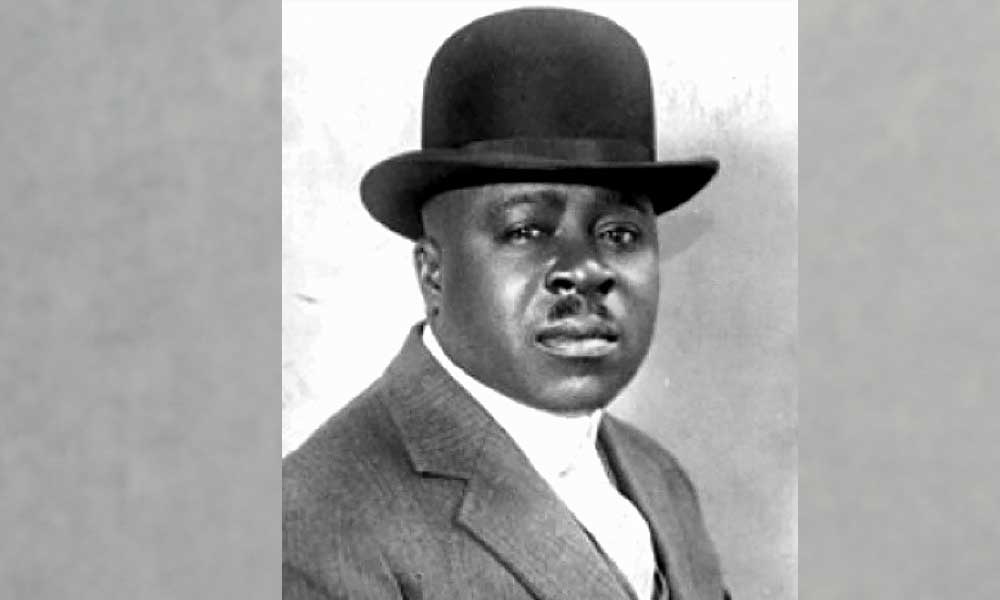

The success of Black newspapers gave rise to larger-than-life publishers like Robert Lee Vann and Robert Sengstacke Abbott, who delighted in the power they wielded. They weren’t nearly as famous as William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer, but they were legends in the Black community. Vann, a prolific lawyer, editor and crusader, ran the Pittsburgh Courier from 1910 until his death in 1940. Under Vann, the Courier claimed a top circulation of 250,000, putting it among the largest Black-owned newspapers in America. Vann was instrumental in moving Black voters away from their post-Civil-War Republican moorings toward Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Democrats. “My friends,” he told his readers, “go home and turn Lincoln’s picture to the wall.”

Like other Black publishers at the time, Vann genuinely cared about the suffering of Jews in Europe, but he also saw it as a chance to highlight the suffering of Black Americans. Vann was quick to zero in on what he and his staff viewed as the hypocrisy of the United States offering safe haven to Jews (even though many Jewish refugees were denied entry) while perpetuating Jim Crow at home. A cartoon in the Courier on April 16, 1938, depicted Uncle Sam astride an open door labeled “Land of the Free—USA,” holding out a hand of welcome to frenzied Jews and others being whipped by Hitler. The doormat reads “Welcome to White Aliens.” But inside the door is a Black figure chained at the ankles, with a noose around his neck. Attached labels read “Discrimination,” “Disenfranchisement” and “Ostracism.”

The accompanying editorial noted the economic discrimination, political disenfranchisement and residential segregation that European Jews were being subjected to. “This SO offends big-hearted Uncle Sam’s SENSE OF JUSTICE that he is offering them asylum. But the subjection of his colored children to economic discrimination, political disenfranchisement, residential segregation, and social ostracism does NOT offend Uncle Sam’s sense of justice.”

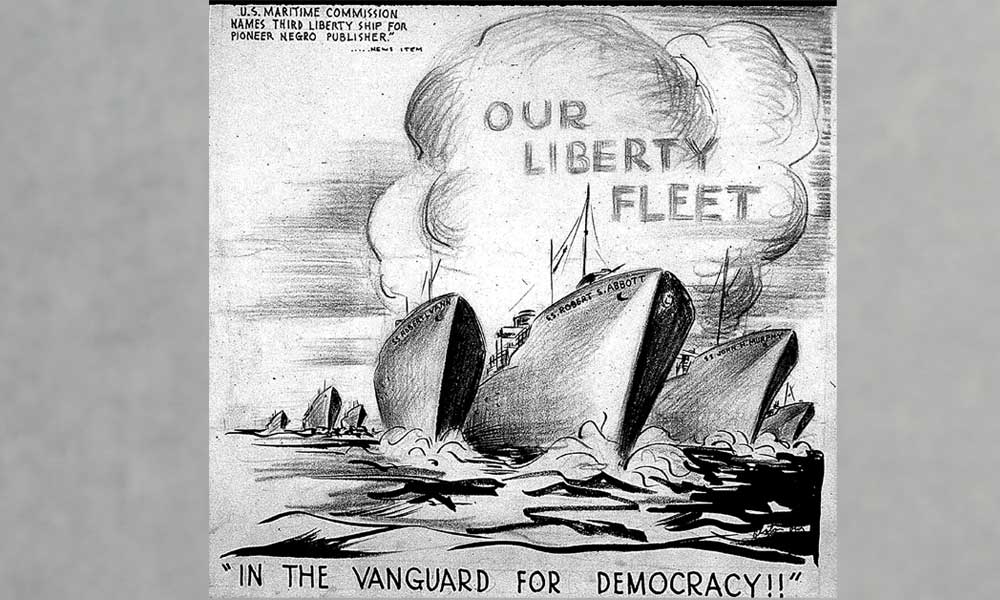

Three years after Vann died in 1940 at age 61, the government christened one of its new, hastily constructed “Liberty” ships as the S.S. Robert L. Vann. It was one of over 2,000 such ships built by the government to ferry military supplies overseas. In all, 17 of them were named after prominent Black Americans, including Booker T. Washington, Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman. The NAACP and other groups pushed the initiative forward to help boost Black morale and encourage Black participation in the war effort. Tragically, the S.S. Robert L. Vann hit an underwater mine in March 1945 and sank, but fortunately all the crew survived.

- Robert Lee Vann (Photo credit: Office for Emergency Management war promotion 1943)

- Robert Sengstacke Abbott

Robert Sengstacke Abbott (1868-1940) was another influential figure. He founded The Chicago Defender in 1905, raising $13.75 for the initial press run, according to a book by Ethan Michaeli, himself a copy editor at the Defender in the 1990s. Abbott succeeded in turning it into a 230,000-circulation giant by the 1920s, making him one of America’s rare Black millionaires. Abbott’s stepfather, John Sengstacke, was biracial and had grown up in Germany as the son of a German sea-captain father and an enslaved woman in Savannah, GA. Abbott took his stepfather’s last name as his middle name, drawing inspiration from his stepfather’s preaching equality as a Congregationalist minister and his publishing a small newspaper in a town near Savannah.

Abbott wrote numerous passionate editorials condemning the Nazis’ treatment of Jews. “German Jews’ Plight Identical with That of Race Here: Nazi Race Hate Same as in U.S.,” the Defender declared on September 14, 1935, after the Nazis promulgated rules stripping Jews of citizenship and civil rights. When he died in 1940, he left the paper to his nephew, John Henry Sengstacke (1912-1997), who became a leading national civil rights figure, successfully pushing for the integration of the military, government jobs and presidential press conferences. He also founded the National Newspaper Publishers Association to strengthen Black-owned papers.

- The Chicago Defender’s John Henry Sengstacke (right), 1942. (Photo credit: LOC)

- President Dwight D. Eisenhower receiving the Robert S. Abbott Memorial Award from The Chicago Defender for his efforts to eliminate segregation in Washington, DC, with John Henry Sengstacke (right) and Thurgood Marshall (center). (Photo credit: National Archives and Records Administration)

Headquartered in a former synagogue in the Bronzeville neighborhood—a partly Jewish area that was fast becoming the center of Black life on Chicago’s South Side—the Defender was a beacon to Black Southerners at the height of the Great Migration northward. Its staff loaded stacks of papers on southbound trains, and in New Orleans or Memphis or wherever the trains stopped, they were distributed far and wide. Historians credit that distribution with inspiring Blacks to leave the rigidly segregated South for what seemed like a promised land. The Defender was their initial guide to jobs, housing—everything they would need to survive in their new world.

In 1909, another Black publisher, James H. “Pop” Anderson (1867-1931), launched a six-sheet newspaper with a $10 investment. It was named New York Amsterdam News after Amsterdam Avenue, the major artery near Anderson’s home on W. 65th Street in San Juan Hill, New York’s primary Black neighborhood before Harlem eclipsed it. (Today, Lincoln Center is located at what was San Juan Hill.) The Amsterdam News later moved uptown along with its readership, becoming an important voice for Black Americans in the nation’s largest metropolitan area, with its long history of Black and Jewish life. Indeed, the newspaper had a front-row seat to the entertainment industry. In 1943, the Amsterdam News wrote about a consortium of Jewish retailers in the Bronx who underwrote screenings of Stormy Weather, one of two movie musicals featuring all-Black casts released by major Hollywood studios that year. Although it featured legends like Lena Horne, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Cab Calloway, Stormy Weather was confined to theaters patronized by Black audiences and suffered from limited distribution. “‘Stormy Weather,’ these merchants declare, evidences the great advancement and rapid achievement that Negro actors and actresses have made in pictures,” read the story in the Amsterdam News, “and they are happy to give it their whole-hearted support.”

America Goes to War

When the United States entered World War II on December 8, 1941, Black newspapers embraced the war effort, but they were quick to frame it as a struggle for liberation both abroad and at home. The Pittsburgh Courier promoted a variation on the Churchillian “V for Victory”—“Double V,” one for victory in the war and the other for racial justice back home. The idea was the brainchild of a letter writer, James G. Thompson, who said the second V would stand for “victory over our enemies from within.” He defined them as bigots who “perpetuate these ugly prejudices” and seek to “destroy our democratic form of government just as surely as the Axis forces.” The Courier picked up the idea and formulated a logo—two Vs surmounted by an eagle. It was soon adopted by other Black newspapers.

Cartoon by Charles Alston depicting Liberty ships: S.S. Robert L. Vann, S.S. Robert S. Abbott and S.S. John H. Murphy. (Photo credit: National Archives and Records Administration)

Discrimination and harassment were a constant presence for both Black soldiers and Black civilians. About 1.5 million Black Americans served in segregated U.S. military units. Many were relegated to menial labor or driving trucks, and thus kept away from the battlefields. Approximately 780 died in combat. (Jews were not kept away; of the approximately 550,000 Jews who served in uniform, 7,000 died.) Those on the home front found increasing opportunity in northern factories churning out war materiel. But tensions between newly arrived Black workers and white counterparts led to riots in cities across the country, the worst occurring in Detroit in June 1943. The Pittsburgh Courier called these riots “pogroms,” noting that the democratic world had expressed outrage when Nazis attacked Jews and Jewish businesses in the 1930s. “Few people expected that within such a short time a similar horror would be visited upon the self-styled greatest democracy in the world, and for the same ‘racial’ reasons.’”

In the early 1940s, American Jews were of course in a state of panic over the fate of their European brethren in Germany and all the territories conquered by the Wehrmacht—including Poland, France, the Netherlands, Belgium and large parts of the Soviet Union. (To say nothing of fascist allies Italy, Romania, Bulgaria and Hungary.)

They knew Jews were being murdered, but solid intelligence was in short supply. That changed when Gerhart Riegner, the World Jewish Congress representative in Geneva, Switzerland, received news—via an information chain that originated with SS and Gestapo chief Heinrich Himmler himself—confirming that the Nazis were planning the mass extermination of all of Europe’s Jews. Riegner passed the information on to the U.S. State Department. Eventually, it filtered to Rabbi Stephen Wise, president of the World Jewish Congress, who broke the news at a Washington news conference on November 24, 1942.

The press coverage of Hitler’s plans was shockingly lackluster. The New York Times, with a robust DC bureau, ran a five-paragraph account by the Associated Press the next day—on page 10. (It should be noted that on the same page, the Times ran a bylined story from London reporting that Nazis had already slaughtered 250,000 Jews in Poland.) Other mainstream papers chose to focus on the ghoulish aspects of the AP story. “Jews Charge Hitler Buying Corpses for Soap, Fertilizer” was the headline in the Fort Myers (FL) News-Press. (In addition to stating that Hitler had exterminated up to two million Jews and aimed to annihilate the rest, Wise had also reported that the Nazis were reclaiming corpses, mostly Jewish, for “such war-vital commodities as soap fats and fertilizer.”)

By contrast, the Black press spoke out clearly and loudly. “Nazi Treatment of Jews Deplored by Negroes,” the Pittsburgh Courier reported on November 28, 1942. The headline writers at Black papers were acutely aware of how to communicate the horror befalling Jews to their respective readerships. “Nazis Lynch 22,000 Jews in Russia,” was the Baltimore Afro-American headline on December 12, 1942. The Chicago Defender summed up the need for Jewish-Black unity in the face of a deadly common enemy in an editorial on December 26, 1942: “All of Negro America is revolted at the monstrous atrocities Hitler is heaping upon the Jewish people. Every section of the Negro people calls for vengeance against the bloodthirsty Nazi butchers…Negro America calls for an end to Hitler and to Hitlerism. Let the sympathy of black men for the stricken Jewish people strengthen the arm of every Negro soldier. The cause of world Jewry is the cause of the Negro people. Fascism must be rooted out from top to bottom.”

Today, this sympathetic coverage of what the Jews were experiencing is viewed by Holocaust educators as a teachable moment. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, offers teachers a ready-to-use lesson plan—“Black Newspaper Coverage of the Holocaust”—geared toward students in grades 7-12. This curriculum is not specifically focused on Black and Jewish students. “The history, and what people can learn by engaging with it, speaks to broad audiences,’’ says Daniel Greene, museum historian and exhibition curator. The curriculum includes a primary-source collection of articles that appeared in the Black press during these years that are part of the museum’s “History Unfolded” database. The database consists of more than 683 articles that appeared in the Black press.

It’s also noteworthy to recall that the support of Black papers for Jews was reciprocated. The 1930s and 1940s were also a heyday for the Jewish press, which was fairly consistent in its defense of Black Americans. Yiddish writers in newspapers like Forverts (“Forward”), Der Morgen Zshumal (“the Jewish Morning Journal”) and Frayhayt (“Freedom”) all wrote about racism and bigotry directed against Black Americans. Frayhayt, the U.S. Communist Party’s organ in Yiddish, championed the Scottsboro Boys case. A Jewish lawyer, Samuel Leibowitz, stood by them through lengthy appeals that saved them from the electric chair. Frayhayt covered the case every step of the way.

But in the more mainstream Jewish press, dismay over inequitable treatment of Black Americans was tempered by ambivalence over the place of Jews in America. “Alongside expressions of sympathy towards African Americans and their plight, reports in the Yiddish press also exposed anxieties about Black violence, and, occasionally, expressions of paternalism or disdain towards Black Americans,” Harvard scholar Uri Schreter wrote in 2021 in the Yiddish scholarly journal In Geveb. “This range of responses reflected many Jews’ experiences of feeling torn between a sense of kinship with a neighboring, oppressed minority, and a desire for their own full acceptance in White America.”

Since Then…

The decades that followed World War II were complicated ones for Black-Jewish relations. Beginning in the 1950s, whites, including many Jews, abandoned urban neighborhoods for the suburbs. The early and mid-1960s were a period of great civil rights partnership and progress, but in the late 1960s the civil rights movement gave way to Black Power and the Black Panthers, who were eager to overturn old alliances.

Israel’s victory in the 1967 Six-Day War changed how some Black Americans saw Israel—with Israel now being perceived as the oppressor.

This change went hand in hand with a growing minority who embraced the Muslim faith, either through the Nation of Islam or otherwise. This and the fight against apartheid in South Africa led to greater identification with the Palestinian cause in parts of the Black community. Later, segments of the Black Lives Matter movement also cast Israel as the oppressor. There was much positive too, but overall, the tectonic shifts of history created rocky outcroppings not easily traversed.

Publications far outside the Black establishment popped up and embodied some of these shifts. One was The Black Panther, published by the party from 1967 to 1980. Another is The Final Call, which in 1979 became the official organ of the Nation of Islam. The Final Call today still reflects the antisemitic views of leader Louis Farrakhan, who famously labeled Judaism a “gutter religion” and hailed Hitler as “a very great man.” Today, the Nation of Islam has between 35,000 and 50,000 adherents, according to estimates, but its influence, especially in inner cities, far outweighs its numbers. The Final Call consistently highlights what it sees as “the crimes of Israel” with recent headlines such as “International Outrage Amid Israel’s Cruelty.”

Yet while the Israel-Gaza War and charges that Israel is committing genocide in Gaza have riled some in the Black community, establishment Black news outlets have generally stayed focused on local manifestations, such as demonstrations and remarks by prominent Black community leaders. The Chicago Defender, for instance, provided extensive coverage of sometimes raucous city council meetings in which members in 2023 condemned the Hamas attacks and then in 2024 called for a cease-fire. On occasion, writers even echo a pro-Israel viewpoint. “Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis are financed by Iran, and geopolitical experts stated that the October attacks marked the start of Iran’s proxy war against Israel,” wrote columnist J. Pharoah Doss in the Defender this past April. “The military goal of Iran’s proxies was to deal such a crushing blow to Israel that it would start the process of Israeli disintegration…The October attacks had nothing to do with ‘liberating Palestinians.’”

Overall, the mainstream Black press today shows little interest in the overall state of Black-Jewish relations, says Pulitzer Prize-winning Chicago Tribune columnist Clarence Page. “It’s become a back-burner issue,” he says, noting that the Black community has “got so much going on with issues of their own.” Denise Rolark Barnes, the publisher of The Washington Informer and former chair of the National Newspaper Publishers Association, agrees that the focus is elsewhere. Like the Jewish press, the traditional Black press is facing existential challenges and has been hit hard by changes in the publishing industry. At the same time, the mission of Black newspapers is to “lead our community to places where they would be accepted, have greater opportunities, or learn how to access the opportunities,” says Barnes. “It’s why Frederick Douglass called his paper The North Star.” In this tumultuous era, with DEI and voting rights and other long-fought-for causes under attack, today’s Black press must remain that same “North Star” to Black America, but its proud legacy of allyship should not be forgotten.