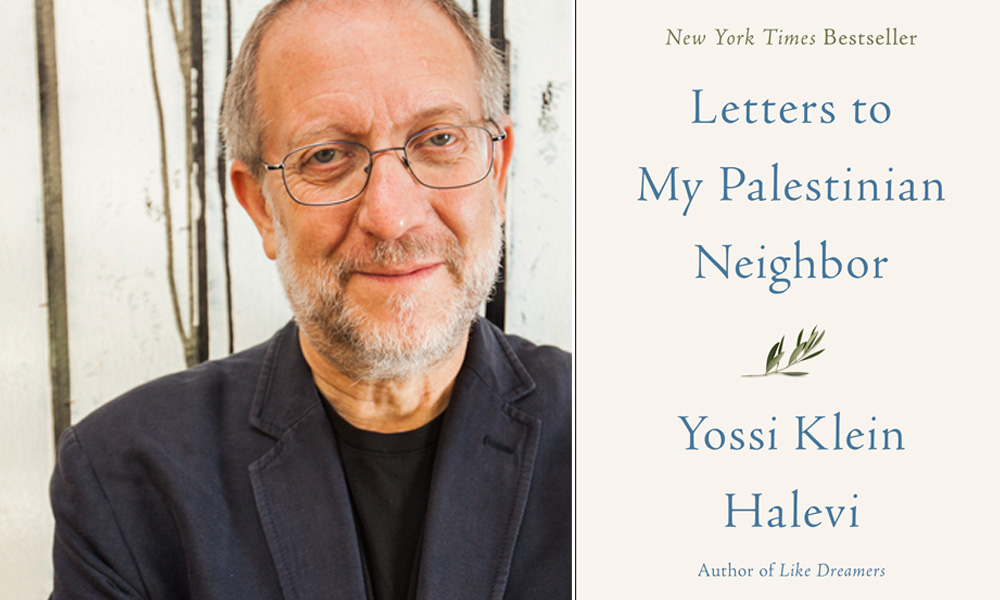

Author Interview | Yossi Klein Halevi

Transcending a poisoned moment

Yossi Klein Halevi has taken on several roles in the Israeli-Palestinian drama since he made aliyah in 1982. He’s been a protagonist in the conflict—“I chose a side when I became an immigrant”—and served in the army during the first intifada. Later, he became a journalist, trying to understand both sides’ complexity in the 2001 book At the Entrance to the Garden of Eden: A Jew’s Search for Hope with Christians and Muslims in the Holy Land. Now he calls himself a “reconciliation activist.” In Letters to My Palestinian Neighbor, published in May, he reaches for that reconciliation through the simplest and most difficult means: talking and listening.

Appearing simultaneously in English and in a free Arabic download from The Times of Israel, the book is constructed as a series of meditations addressed to an unseen but imagined “neighbor,” a Palestinian who lives across the separation wall from Halevi’s East Jerusalem apartment. Halevi seeks to tell this potential reader his story in a way the other might conceivably be able to hear. This is not his first experience with such dialogue. Several years ago, he and an imam friend founded the Hartman Institute’s Muslim Leadership Institute, which brings young North American Muslim leaders to Jerusalem to engage with the Jewish story. Now, Halevi wants those to whom he’s been listening to listen in their turn.

The letters are personal and conversational, trying to convey how it feels to be a Jew who believes implicitly in the Jews’ right to be in Israel but who also wants to avoid “the fatal flaw of the settlement movement: the sin of not seeing, of becoming so enraptured with one’s own story, the justice and poetry of one’s national epic, that you can’t acknowledge the consequences to another people.” He promised he would engage Arabic readers directly and respond to any non-abusive feedback, no matter how negative. Moment’s Amy E. Schwartz spoke with Halevi about the responses he received and his hopes for the future.

How have Arabic-language readers responded to the book?

Responses so far have ranged from the predictable—anger, hatred, threats—to gratitude and curiosity. I’ve been invited for coffee in Nablus and Jenin. I’ve also been told I’m a Zionist colonialist who’ll be expelled from the land when there is peace.

One young man who grew up in a refugee camp near Bethlehem, who now lives in the United States, is writing back to me a series of “letters to my future Israeli neighbor.” He says that as long as I’m a member of the occupation, we can’t be neighbors, but he wants to be someday. He writes that his grandfather has a key to the family’s lost house in the Galilee, and this key is part of his family inheritance. He says he has no right to repudiate the key, but he is not bound to politically implement the implications of having the key; we need, he says, to separate the “right” from the “return.” Palestinians will return to a Palestinian state, he thinks, but not to the State of Israel.

I was happy about that reaction, because he’s using language that directly mirrors the language I used in the book about the settlement movement. The settlement movement, I wrote, has in principle a completely justified historical claim to all of the land, but in practice we need to separate that historic right from its actual political implementation. Another way of putting it is that the State of Israel and the land of Israel cannot be the same. Likewise, the state of Palestine and the land of Palestine cannot be the same. And the book, I hope, offers a vocabulary for thinking and talking about that. I see it as an attempt to model a possible conversation.

So far, we’ve had only a few hundred downloads of the first three letters in Arabic. We’re issuing the ten letters in serial form, one at a time every few weeks. The editor of the Times of Israel page, a Palestinian Israeli, felt that we should go slowly and give people a chance to respond to the ideas. They’re familiar to Jews, but virtually unknown in much of the Arab world, where Jews are considered simply a religious minority—which is how they experienced us for many centuries—not as a people with an attachment to a nation. I can’t tell you how many times Palestinians have said to me, “I have no problem with Jews as a religion, but they have no claim to the land.”

These were the issues I felt an urgency to explain to Arab and Muslim audiences, because the absence of legitimacy is to my mind the root cause of this conflict. If we can get a discussion going about who the Jews are, about peoplehood and its relationship to religion, those are life and death questions for Israel and its neighbors. The idea of Jewish identity, land and sovereignty is the heart of the book, and it’s not an easy argument.

Have any responses made you uncomfortable?

This is such a poisoned moment. The letters can’t be read separately from the context of our time, so Gaza, and Jerusalem, and the 70th anniversary of the Nakba all play into the intense emotions. Usually, when you are on a book tour, and people show up and join the line to get the book signed, it’s a pretty friendly audience. With this book, I don’t know from minute to minute what’s coming at me. It’s exhilarating but also unnerving. I was signing books in San Diego, and an elderly Palestinian couple came up. The woman said, “I was born in Jerusalem, but now I can’t go back. Why is it fair that you can move to Jerusalem, but I who was born there can’t?” I’ve heard this argument over the years, but this was said to me not in anger but in deep sadness, and I shared that sadness with her.

What about Jewish responses?

The response among Jews has been—interesting. I’ve been vehemently denounced by the far right and the far left. The leftist website Mondoweiss claimed I had written that if you’re an anti-Zionist, you’re not Jewish. It’s simply ludicrous to say that. What I said in the book was that a deep attachment to the land of Israel has always been a foundational part of Judaism, that there’s no Judaism without the land of Israel. But just as we have Jews who are complete atheists and violate every law they can in the Torah, and they’re still Jews, of course you can be a Jew and not have a relationship to Israel.

The far right attacks me pretty regularly, and one article in the right-wing FrontPage Magazine accused me of pandering to anti-Zionists. I like those two pieces very much, because they really lay out the pathology of Jewish discourse in our time. It’s essential that the Jewish community not let its discourse be hijacked by lunatics of the far right and left. It’s being subverted; it’s being poisoned. And I believe that organized groups on both the racist Jewish far right and the anti-Zionist far left both need to be quarantined from Jewish discourse.

The State of Israel and the land of Israel cannot be the same. Likewise, the state of Palestine and the land of Palestine cannot be the same.

But you’d talk to Palestinians who held those same anti-Zionist views. Of course.

There are two kinds of conversations. There’s your own communal family discourse, and then there’s the discourse across boundaries. In dialogue with Muslims, my starting assumption is that our two communities are in a deep state of mutual hostility, and therefore it’s necessary to talk despite any disagreements. For example, I was teaching a class on contemporary Jewish identity to the first cohort of the Muslim Leadership Institute. Someone there made a comment about Israel and the Holocaust that I considered hateful: something like, “How can Israel be doing the exact same thing to the Palestinians that the Nazis did to the Jews?” I paused and asked myself—for quite a long time—how to respond. Finally, I said, “If you were a group of Jews, or for that matter Christians, I would walk out the door right now. But because our communities are often at war with each other, I’m committed to sitting at the table with you, if you’ll sit with me.”

Ultimately, the person who had made the comment decided to go to Poland on his own on a Holocaust pilgrimage. I don’t know how much impact that particular moment had. I think it was cumulative.

Does the rise of more virulent anti-Semitism among radical Islamists make your work more difficult?

All I can say is that those people aren’t my partners. In religion, you actually can pick and choose which parts of your scripture you’re going to highlight and which parts you’re going to downplay. In normative Judaism, for instance, we downplay the verses about slavery.

So radical Islamism—not Islam—emphasizes certain things that are problematic from our point of view and promotes interpretations that highlight the most anti-Jewish doctrine. And my allies do the opposite. They do what I do with my tradition: quote those verses that promote an interfaith approach. And one can find in our vast traditions many texts of both kinds.

Do you see anti-Muslim racism on the right?

Oh, sure. I get it on my Facebook page all the time. It’s “the Arabs. They’re all terrorists and Jew-haters. All the Palestinians are terrorists—except there’s no such thing as Palestinians. But if there were, they’d all be terrorists!”

What have you learned about disagreeing successfully?

A friend has a line I like: “The Israeli-Palestinian conflict is not going to be resolved in the Boca Raton synagogue.” I think it’s a profound statement, because we argue as if the outcome of our argument is going to resolve the issue. And I think we all need to take a deep breath and have a little proportion.

Politics has become a kind of theology. Political ideologies are human constructs, but nowadays we argue about politics the way we used to argue about religion, as if politics were revealed truth. And yet we’ve seen the failure of so many political ideas in our time. I remember my friends in the peace camp assuring me, with these deeply satisfied smiles, that Oslo was a done deal. And I remember my friends in the settlement movement in the 1980s, before the first intifada, telling me with those same smiles that the settlements would bring security and the Arab world would swallow our “facts on the ground.” Well, the settlements didn’t bring us security, and Oslo didn’t bring us peace. We need a little humility about our political ideas, and I wouldn’t call humility the defining trait of Jewish discourse in our time.

We’re all imperfect beings. Most of us are well-intentioned, and most of us want the best for Israel and the Jewish people. I’m not asking for artificial unity, but let’s give one another a bit of credit.