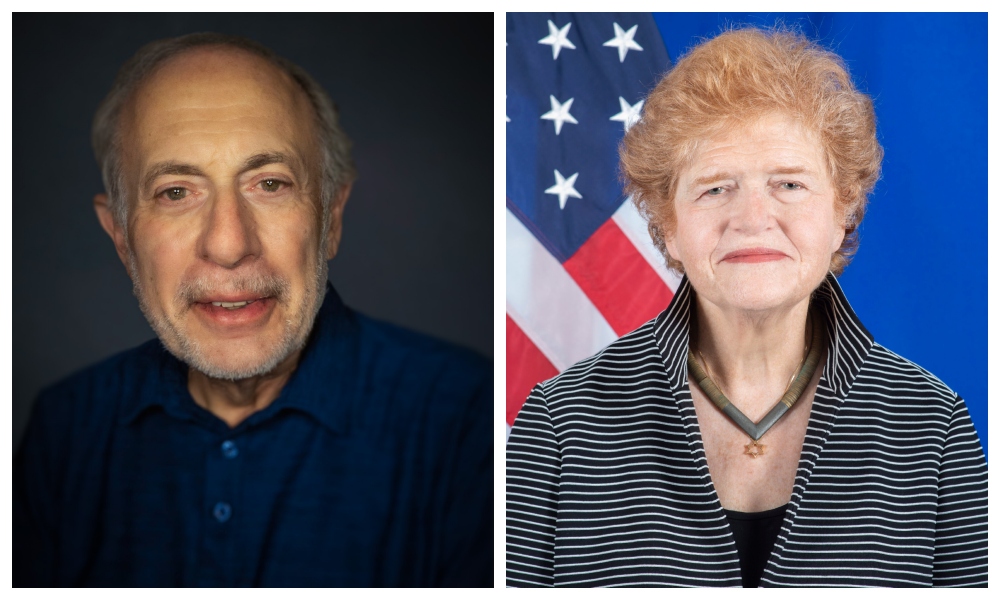

Last fall, Moment Special Literary Contributor Robert Siegel, former senior host of NPR’s All Things Considered, interviewed Ambassador Deborah Lipstadt as part of Moment’s 2022 Gala and Awards ceremony. Lipstadt, who serves as the United States special envoy for monitoring and combating antisemitism, was honored with the Ruth Bader Ginsburg Human Rights Award. She spoke about rising antisemitism in various parts of the world, her hopes for the expansion of the Abraham Accords, myriad issues she encounters related to religious freedom and more.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length. Watch the unedited interview here.

Your mission at the State Department “is to monitor and combat antisemitism and to advance U.S. foreign policy to counter antisemitism throughout the world.” So where do we stand? Is antisemitism dangerously on the rise, and what can the United States do about it?

Well, I think it’s on the rise in different forms. It’s on the rise certainly in physical attacks on Jews, some of which don’t grab headlines because they’re only—and I put “only” in big quotation marks— knocking someone’s hat off if they’re wearing a black suit, white shirt and a Borsalino or some other kind of hat, or someone is harassing a woman who’s pushing a baby carriage in Brooklyn, Antwerp, Paris or someplace else. We have those kinds of things and then we have more serious incidents as well. I do know that people are more conscious of antisemitism and possibly reporting it more, so I take that into consideration. But the numbers, the increase of numbers, are so dramatic that even if you qualify for people’s heightened sensitivity, it’s still on the rise.

Why do you think that is? How do you understand its cause?

It’s never just one reason. In some ways we’re in a perfect storm. We have groups (e.g., white supremacists, separatists) who feed on antisemitism, who nurture their followers on antisemitism, and they are becoming more emboldened in this country and others as well. The irony is sometimes they demonize the Jew but then proclaim their great support for Israel. We also see it coming from other places on the political spectrum, certainly not with the same violence and vituperativeness, but in a very effective way in terms of their objective.

I describe social media like a knife. A knife in the hands of a surgeon can save your life. A knife in the hands of a murderer can take your life.

The other thing we can’t ignore is that there’s a delivery system now that didn’t exist years ago. When I first started working on Holocaust denial issues and wanted to get materials about it, they were sent in a plain envelope to a PO box because it was illegal for them to go across international lines, and different countries would stop them. Now all you have to do is go on Google or Twitter or wherever it might be. And not only can you put it up, but you have an audience and a megaphone.

To what extent is the rise of social media giving bigger audiences to ideas that have always been there but have been on the sidelines before?

I don’t want to beat up on social media. I describe social media like a knife. A knife in the hands of a surgeon can save your life. A knife in the hands of a murderer can take your life. It’s how social media is used; it’s how the platforms monitor themselves and live up to the standards they proclaim for monitoring content on their sites. So social media is a big part of the problem, but it’s also a big part of how we communicate and further aspects of Jewish life. So it’s a tricky situation.

Which countries give you the greatest concern?

I’ve just come back from Western Europe, and there’s something to be concerned about in many of those countries. I’m going to South Africa, which has a community that’s under pressure. And not so long ago, I was in Argentina for the 28th anniversary of the AMIA bombing—the AMIA, which is their equivalent of the JCC. I’ve been in Auschwitz-Birkenau with people who were there as prisoners. It’s an overwhelming, indescribable experience. But I felt much of that emotion when I stood before the now rebuilt AMIA building. Each of us had been given a photograph of a victim of the bombing before we entered the memorial’s vicinity, and the moment the sirens went off, we held them up. It was overwhelming because 28 years have passed and it still hasn’t been solved. And you were standing among people who had family in the building, knew people in the building, had been in the building. So there’s no dearth of places to which we can look for problems.

Antisemitism is like the canary in the coal mine of democracy. It is a threat, a warning.

At the same time, let me focus on some of the positives.

I’ve been to the Middle East. I was in the Persian Gulf states of Saudi Arabia and the UAE. No one dreamt that the Abraham Accords would bring these results. I’m not talking so much about the relationship with Israel. That’s the responsibility of other people working not very far from where I’m sitting right now in the State Department. Rather, in terms of those countries’ willingness to address issues of antisemitism and to recognize that attitudes toward Jews and the geopolitical situation in the Middle East—Israel and the Palestinians—should be treated as two separate issues.

During my trip to Saudi Arabia, which is not yet part of the Abraham Accords, I visited an older sheik. He said to me, “Ambassador Lipstadt, if Israel solved the Palestinian crisis, there’d be no antisemitism.” As I’m listening to him, I’m thinking as an academic. It seems to me there was antisemitism before there was an Israel-Palestinian problem, before there was an Israel, before there was Zionism.

But I didn’t want to get into a history match. Instead I said, “In my country there was a surge, an absolute skyrocketing, of contempt for Muslims after 9/11. So much so that the New York City council forbade permission for the building of a Muslim community center and mosque adjacent to Ground Zero.”

And then I said, “Many people I know, including many Jews, thought that was the wrong decision. Why should a Muslim who wants to go and worship, pray, or take his or her family for different events at a community center be prevented from doing so because other Muslims had attacked the World Trade Center?” He said, “You’re absolutely right. There is no connection. That’s a political issue and this is a hostility towards a religious group.” I paused for a dramatic moment and then said, “Well, that’s the same thing with antisemitism. Irrespective of how you feel about the Israel-Palestinian crisis, that doesn’t give you license to go around hating Jews or fomenting hatred of Jews.”

When I speak out, it’s in consultation with the wonderful team in my office and colleagues across the building. I’m speaking in the name of the United States government.

Of course Saudi Arabia was, for many decades, exporting imams to Europe and other places to preach antisemitism. Anyway, I met with fairly high-ranking ministerial officials and they listened to me. When I entered one deputy foreign minister’s office, he put out his hand and said, “I come from a city of Jews.” And I said, “Medina.” He said, “Correct.”

Does that mean everything is solved? No, of course not. Does that mean there aren’t human rights problems in Saudi Arabia? No, of course not. There are human rights problems in our country too. But does that mean we’re opening a line of communication? I think so, and that’s affirming.

I’m curious about what you have to say about the war between Russia and Ukraine. If you told me a few decades ago they were at war, I would assume that it must be bad for the Jews. Instead, Ukraine has a Jewish president, had a Jewish prime minister and, for all of Vladimir Putin’s sins, one thing he doesn’t seem to be is an antisemite, unless I’m not reading carefully enough.

In the opening days of the war, and then again more recently, Putin talked about the denazification of Ukraine and going after the Nazis. It was Holocaust distortion 101. And that was clearly disturbing. Then at another moment in the war he, or the Kremlin, warned the Jews and threatened to close down the Jewish Agency for Israel in part because of Israel’s seemingly limited support of Ukraine.

I’m very careful of labeling anyone an antisemite, but I know when I see actions that are antisemitic or foment antisemitism, and some of those are coming out of Russia. This is not a good situation at all.

I asked you earlier about social media—two huge social media companies, Facebook and Twitter, are American companies, but the vast majority of their users are in other countries, some of which have laws against hate speech. Have you ever found yourself advocating in other countries for an approach to antisemitic speech that would be thrown out of court in the United States as an unconstitutional violation of the First Amendment?

As an American diplomat, I don’t do that. But I do say, in this country and other countries, that I hope these platforms would abide by their own set regulations and standards. I meet with my counterparts in other countries, who are freer to call on these companies to regulate. Because, as you rightly put it, in the United States these cases would be thrown out of court because of First Amendment rights. But I think there has to be some sort of sense of responsibility because it can be very dangerous.

You have encountered some interesting issues in your role at the State Department that I hadn’t expected, one of which involved a proposed European law on the humane slaughter of animals. It claimed that people shouldn’t be able to slaughter livestock without first stunning them. What was the problem here?

The problem, which applies equally to Muslim and Jewish communities because of Halal in Muslim ritual and Kashrut in Jewish ritual, concerns religious animal slaughter. When animals are slaughtered to be eaten according to the rules of Kashrut and Halal, they should be alert and then killed efficiently. In some countries there have been laws forbidding it, more so in recent years as an anti-Muslim thing or as a protection of animals issue.

Just last week I was at a European Union meeting and virtually every EU country was represented to talk about the attempted bans on religious slaughter. We made an argument that didn’t get into stunning, what works better and what doesn’t, how fast the animal dies, and so on. We said, “This is a matter of religious freedom.” One country that’s considering this ban has written religious freedom into its constitution, and if you proclaim religious freedom, then you’ve got to allow people to practice their religion, especially if the bill you’re proposing has exemptions for hunting, fishing, bullfighting, etc. Not exactly humane ways of killing an animal, right? So it just seems strange that this should be such a focus.

But I wasn’t there saying this was antisemitic. I did argue that in our lifetime, two out of three Jews were murdered on the European continent. If you travel through Europe, you see that many cities have a gorgeous synagogue, lovingly restored by the community, the government or UNESCO. Or the synagogue is a museum, a place for tourists to visit. And it’s not because the Jewish committee said, “Oh, let’s leave and move someplace else.” It’s because they were murdered. So, anything that’s going to make Jewish life less viable today, particularly on a continent that once had the most vibrant Jewish life, is something that I’m concerned about.

You are now an ambassador, but you’re also known for your work as a professor at Emory University and your landmark victory in a British courtroom against the revisionist historian David Irving, who sued you for libel for calling him a Holocaust denier. What can be done as an ambassador that you couldn’t do as a private citizen?

Deborah Lipstadt celebrating her victory outside the courthouse.

© AP Images

When I was in the academic world, I had a lot more freedom. I could write what I want, say what I want, go where I want. And I taught three courses a year and wrote a lot. And, as I said to someone, “that was a full-time job.” In fact, when I got the call from the White House saying that the president was planning to nominate me for this position, I had a moment of hesitation. Do I really want to leave this job to work in one of the most complex bureaucracies in the world, the United States Department of State?

And I said to a friend, “I’m not sure I’m going to do it.” And she said to me, “Deborah, you have to do it.” “Why?” I asked. She said, “Because you can make a difference.” And it brought me full stop, because I think so many people would like that as their epitaph at age 120, as we say in Jewish tradition: “You made a difference.” That’s what I’m trying to do that I couldn’t do before.

Antisemitism is often called the longest or oldest hatred. It’s so baked into the weeds, into the soil of civilization.

So how do I make a difference? First, I had a pretty big megaphone before, but I’ve got a much bigger megaphone now. I realized that just a few days into the job. I was sitting across from the CEO of a very large corporation, which had engaged in some acts that clearly were antisemitic, or could be interpreted as antisemitic, against American citizens. And I said, “We’re very concerned about that.” And I looked at his face and knew he heard the United States government speaking. Of course I had been empowered to do that by my boss, Secretary Antony Blinken. So, when I speak out, it’s not me deciding what I want, it’s in consultation with the wonderful team that I have in my office and colleagues across the building, and I’m speaking in the name of the United States government.

That’s an overwhelming, awesome privilege and responsibility. But there’s another part, which I didn’t anticipate. I have the opportunity to ensure that the fight against antisemitism becomes a fundamental part of American foreign policy. So when the supreme leader of Iran, Ruhollah Khomeini, speaks out in the most antisemitic fashion, my office works with colleagues that deal with Iran and the Middle East to respond. Then the State Department’s spokesperson speaks out and reiterates our response.

I may give up a little bit of my freedom, say to write an op-ed for Moment, or The Washington Post or wherever it might appear, but I’m ensuring that the message goes out, that the fight against antisemitism is something of prime importance to this government. I’ve talked to the secretary about this and, while less so, certainly to the president and the vice president as well. And they get that antisemitism is like the canary in the coal mine of democracy. It is a threat, a warning. If you’re an antisemite, then you think, well, the justice system isn’t fair because it’s controlled by Jews. The government isn’t fair because it’s controlled by Jews. The media isn’t fair because it’s controlled by Jews. You lose faith in the democratic institutions. As a historian, I can think of no democracy that tolerated antisemitism and remained a vibrant democracy.

The best case in point is Weimar Germany turning into Nazi Germany. I’m not suggesting that a Holocaust is looming or a Nazi Third Reich equivalent is looming. I’m not suggesting that at all. I’m looking at Weimar Germany as a fragile democracy that was beginning to thrive, but as the antisemitic forces, along with other forces, became stronger and stronger, its fate was doomed.

You’re reminding me of Poland in 1981, when an antisemitic group emerged on the political spectrum shortly before martial law was declared. And I remember asking, “How can you have an antisemitic movement when there are virtually no Jews here?” And a very wise Italian journalist told me, “You really don’t need Jews for antisemitism.”

Antisemitism without Jews shouldn’t surprise us because antisemitism is often called the longest or oldest hatred. It’s so baked into the weeds, into the soil of civilization, starting with the New Testament depiction of the death of Jesus and how that depiction was used by subsequent leaders of the church. I’m not suggesting it had to go in that direction, but outside of Notre Dame in Paris there are two statues: one is Ecclesia, a beautiful woman who symbolizes the church, and the other is Synagoga, a woman whose hair and dress are disheveled, her eyes covered by a serpent. In other words, this is the church and this is the devil, the synagogue. It’s there so deeply that it’s hard to fight. Now, I don’t want to suggest it’s only the church. It’s all over the political spectrum. It’s ubiquitous.

I recently read about the anniversary of the Tree of Life shootings in Pittsburgh. There was a commemoration of the victims and a man was quoted saying, “a 50-year vacation had ended.” Do you ever have the sentiment that the time period when antisemitism was politically, and even to some extent socially, unacceptable in our country is now over?

I think that’s very well put. To some degree, I think you’re right. I’m hoping I can help change that. I remember visiting countries in Europe in the 1980s and ’90s, even into the aughts, and wanting to find a synagogue. And people would say to me, “Oh, when you get to the street, look up and down, and when you see the gendarmes with their machine guns, you’ll know you found the synagogue.” Today the same can be said for most synagogues in America. Either they have an armed officer outside and congregants patrolling, or maybe just congregants. But we haven’t gone through the front door of my synagogue in four years.

One last question. You’ve been awarded Moment’s Ruth Bader Ginsburg Human Rights Award. Did you ever meet or know her?

We were both honored once at an event, and I sat next to her, but I didn’t really know her. When you look at her story and you hear her deep-seated commitment to equality, to fairness, it comes out of such Jewish roots. And when she fell asleep during the State of the Union address, and afterwards she said her granddaughter called her and said, “Bubbe, you can’t do that!” my heart melted.

2 thoughts on “An Interview with Ambassador Deborah Lipstadt”

One of the best in her field. America and the world at large are fortunate to have her voice, her opinion, her experience and knowledge in history, current affairs and Anti-Judaism.

Thank you, Ms. Deborah Lipstadt. May you live to 120 years.

I am so glad we have Deborah Lipstadt in this position.

On the other hand, we have to HAVE this position.