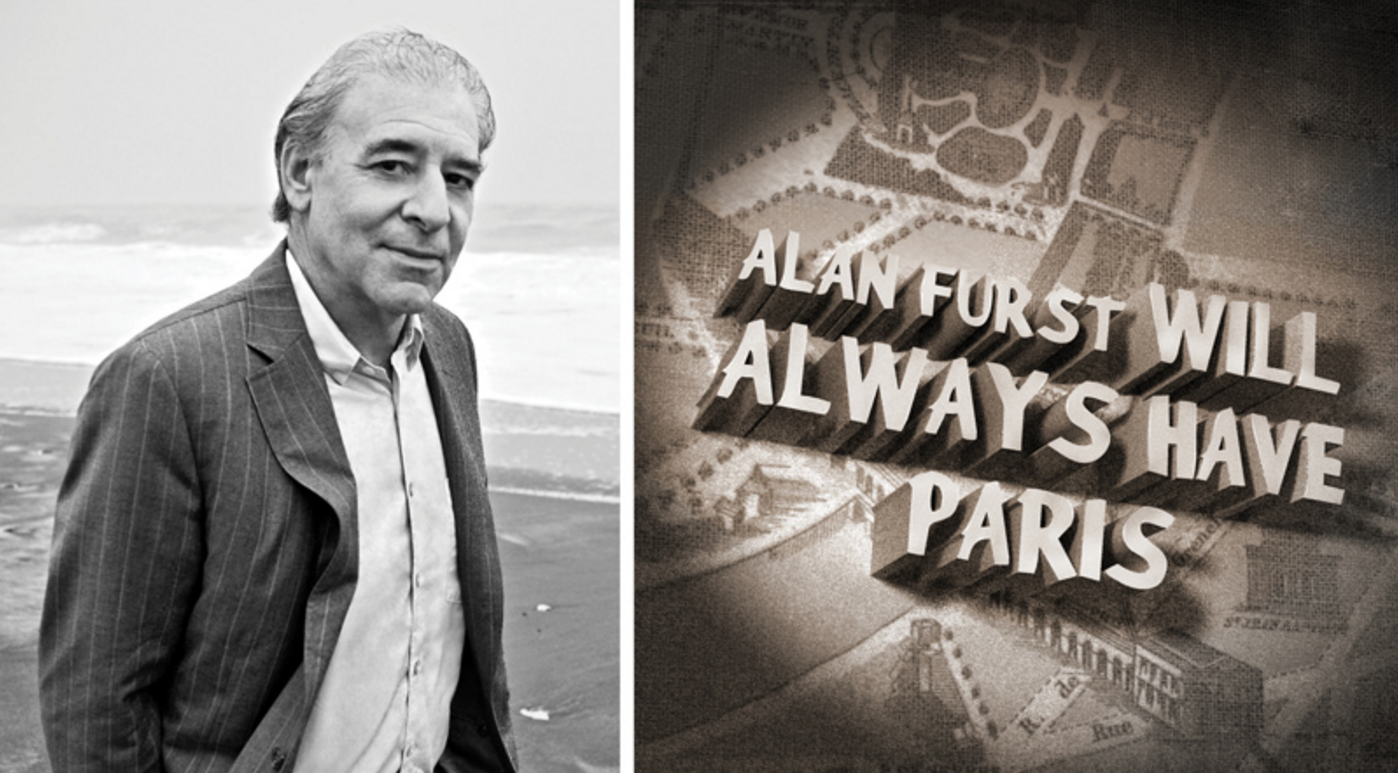

By Sarah Breger

In each of Alan Furst’s 14 novels about spies—not spy novels, he insists there is a difference—characters inevitably end up dining at Brasserie Heininger in Paris. The fictional restaurant, based on the real Brasserie Bofinger, with its opulent marble staircase and shucked oysters, represents the glamour and the joie de vivre of 1930s Paris, a city he calls “the heart of civilization.”

Furst lived in Paris for many years, and it was there that he wrote Night Soldiers, the first of his historical thrillers. At 75, Furst is a rarity in the publishing world, both a critical success and a consistent best seller. Furst’s novels, set during World War II or the years preceding it, feature opposing intelligence agencies, reluctant heroes and nations on the brink of war. His atmospheric books are full of shadows, doubt and unanswered questions. Whether writing about military blueprints in Warsaw or German refugees in Salonika, Furst’s gift is an extraordinary sense of place. In his new novel, A Hero of France, the place is 1941 Paris. The French are unhappily being occupied by the Germans, and the book’s hero, Mathieu, the leader of a French Resistance cell, navigates a web of collaborators,informers and spies, to fulfill his clandestine assignments.

Today, Furst lives in Sag Harbor, but this self-described “typical Upper West Side Jew” still dreams of a Paris that’s long gone. Furst speaks with Deputy Editor Sarah Breger about his new book, anti-Semitism and why he considers himself a “novelist of consolation.”

Why do you write exclusively about the period between 1933 and 1942?

It’s the most incredibly intense period. If you look at the chronology, Hitler comes to power in 1933; in 1934 and 1935, there are purges in the U.S.S.R; 1936 is the Spanish Civil War; 1938 is Munich and the betrayal of Czechoslovakia; 1939—the invasion of Poland; 1940, the invasion of France and the Low Countries; 1941, the invasion of the Soviet Union. But also, if you look at the literature, people were incredibly passionate. A lot of people didn’t think they were going to live out their lives. Life was so dangerous in so many ways. At the same time, Casablanca was made. There was a huge flowering of the arts. I don’t know what got into the world, but it suddenly became incredibly dynamic—and perfect for a writer like me. I couldn’t write about the 1950s.

Why not?

It’s John le Carré who writes about the 1950s. In the 1930s, everybody knew what everything meant. It was clear. Good and evil, sharply defined, as they aren’t in le Carré’s novels. He writes about the hall of mirrors—what does this mean, what does that mean? He has the perfect personality for it. He’s chilly, ironic, cold, distant. Very funny. He’s an excellent, beautiful writer. Can he write! But that’s his period. My period is more from 1933 to 1942.

How much of your stories and characters are based on fact, and how much is from your imagination?

None of it is made up. Well, here and there. If it wasn’t really this café, or if it wasn’t really that date, it was close to it. I feel obligated to honor the truth, because so many people had their lives end in that period. To honor their existence, you can’t go making things up. You have to say what history says to be true. History is a much better writer of fiction than any person I’ve ever met, and certainly better than me. All I do is sort of slip my characters into the historical stream.

Are there any historical characters you’re particularly fascinated by?

My “Jewish novel,” as I call it, Dark Star, is about the Soviet writer Ilya Ehrenburg. There are several others who have served as models, because they led extraordinary lives. Ehrenburg is described as a “Russified Polish Jew.” He spoke, you know, all those languages.

Everyone spoke so many languages then.

It’s astonishing! Now, if you go around the United States, people don’t speak another language, or read it, or care. And, okay, it’s not for me to judge and make accusations. The world is the world. It goes on as it goes on. But I don’t have to approve of it.

How do you research your books?

The best sources for me are contemporary journalists of the period. Another good source is self-published memoirs of people who lived through the period, some of which are incredibly good. These are not going to be books from Doubleday. I always encourage audiences when I speak: If your Aunt Edith has some story about how she sneaked into Switzerland in 1943, encourage her to write it down. Because those books go to the Library of Congress, and that means that history is preserved. Also, historians who wrote right after the war are sources. I also read the novels of the period, some of which are very interesting. And I like reading autobiographies of the period. And last are today’s historians. But they tend to be academic and argumentative—they fight about everything.

Do you spend most of your time reading?

Here’s how I work. I will write about three hours a day. I can’t do more than that. My brain just goes dead. But my afternoons, I have a lot of errands. Like everyone else, I have stuff I have to do. I have a house to take care of. I also watch a lot of sports. Because what am I going to do? Finish writing and then go read a novel? I don’t think so. I do other things. I watch a lot of television. I do a lot of research in the afternoon. That’s my favorite time. I can just lie there, with a pen and a piece of paper, and read a book, and make notes in the back. My books are covered with stuff. Thank God I don’t use the library.

“History is a much better writer of fiction than any person I’ve ever met, and certainly better than me. All I do is sort of slip my characters into the historical stream. ”

Has anything particularly surprised you in your research?

One of the things I’ve discovered in reading historical accounts is that people had the most incredibly elaborate, brilliant methods of bribery. In one of my books I have a true story where two of the characters bribe an Estonian general by giving him a chandelier. They take him out for dinner. There’s a beautiful chandelier. And he says, “Oh, wouldn’t that be wonderful.” And they say, “Well, we’ll get you one.” Another common method was going to the racetrack, and making bets. The [briber] would go to the window, and would bet on all the horses, and then would come back and say to the person, “Oh, you won!”

In this new book, as well as in your other books, the theme seems to be “What would you do in this situation?”

Yes, it’s true. My latest book is about a group of upper-middle-class people who decide to resist the Germans. And I said, “So, fine. Which of your friends would you trust with your life?” When you start thinking about it that way, it’s somewhat chilling.

If you read the literature, the most astonishing people became friends and protectors. Yad Vashem, the Avenue of the Righteous—I think most of the people there are Polish Catholics. And at the same time, you know, the Poles were not great to the Jews, especially after the war. That’s the part that hurts. But this goes on and on. I say to people, “They were killing Jews the day I was born. They’ll be killing them the day I die. Why? I don’t know, really.” But it is true of our people, that we bear this burden. And we have to learn to live with it or adapt to it.

I really feel sometimes, after writing for a day, that I want to take an anticruelty pill. I almost can’t stand it anymore. How can people be like that? How on earth can people be like that? But they were.

In all of your books, there is usually a Jewish character, either at the forefront or sometimes just in the background. How do you decide how much of the Jewish element to put into your books?

I’m not a Holocaust writer. But the situation of the Jews in Europe during my period was prominent. So they have to be there; they have to be acknowledged; they have to be part of things. They’re not the whole story, but in my most recent book, for example, there is one Jewish character. The other people are French. He’s the one who’s been damaged—who, as a Jew, has lost his job as a teacher of mechanical engineering, and he’s the one whose family lost a shoe business. And he’s the one who wants revenge.

In many of your books, Jews are portrayed as these “tough Jews.” Is that an attempt to counteract stereotypes, or a reflection of reality?

It was a reflection of reality. Some Jews were passive and didn’t make it. Others were not and still didn’t make it. But if you were going to survive in a world where you were being persecuted, you had to do something, and one of the things you might have done is strike back. When you read about it, the really tough, murderous gangs in the French Resistance were Jewish teenagers. I mention that in the book and cite one of the actual gangs that was very famous. I guess they were all ultimately killed, but they really slaughtered a bunch of Germans. Payback.

Would you ever write a Holocaust novel?

I don’t think so. I’ve read the literature, and of course it breaks your heart. But I can’t compete with Elie Wiesel. Or, better yet, I can’t compete with Primo Levi.

“We’re swinging more to kind of very right-wing period. It’s all over Europe. It’s in Hungary, it’s in Poland. It’s like a virus that the human population doesn’t seem to be able to get rid of.”

I noticed a common refrain in many of your books: that Hitler said exactly what he intended to do before the war, but no one took him seriously. I couldn’t help but be reminded of current U.S. politics and Donald Trump.

It happens all the time. People say, “Do you do this on purpose?” No! But if you tell the truth, and if you’re accurate, that’s what will happen. You can see we’re swinging more to a kind of very right-wing period, and it’s not just Trump. It’s all over Europe. It’s in Hungary, it’s in Poland. It’s like a virus that the human population doesn’t seem to be able to get rid of. It keeps coming back.

I remember when I was living in Paris, the war in Yugoslavia started, and they were killing Bosnian Muslims. We had a duplex in the Marais, and I’m lying in bed, underneath the sloping roof, listening to the BBC. It’s very static-y, and it’s talking about a war that’s about 800 miles away. And I’m going, “Oh, no. Not again.” How could this ever happen again? But it does.

How often do you go back to Europe?

I don’t go anymore. I left Paris about 20 years ago, and almost by accident, my wife and I bought a house in Sag Harbor for little money. It was one of those lucky strokes. And rather quickly, I fell in love with village life at the end of Long Island. I can’t go to the post office and not spend 20 minutes there, because I keep meeting people I know. Same way with the grocery store. So I now consider myself rusticated. Anyhow, the Europe I’m writing about is gone. It’s a fond memory, and one of the things I’ve said about my new book, is that it’s a love letter, a valentine to a lost Paris of another time.

I read somewhere that you describe yourself as a typical Upper West Side Jew. What does that mean?

It means that I went to public school, then I went to Horace Mann. The Upper West Side Jew–we all probably hung out at the same places. We were chased around by some of the tough kids who lived east of Broadway. Recently, I was walking with a friend of mine who lived on Columbus Avenue. And he said, “Have you ever been here before?” I said, “Never walking. Always running!” My bar mitzvah preparation was at Temple Rodeph Sholom, which was at 83rd and Central Park West. So I had to cross enemy territory to get there. And again, other Jewish kids from the West Side would say the same thing. It was a culture. But it’s all gone. It’s all changed now.

What book most influenced you?

I really think that the book that influenced me most was Eric Ambler’s A Coffin for Dimitrios [published in 1939]. My paperback copy, which I still have, has on the inside of the cover in the back written in pen, on an airplane, the first paragraph of Night Soldiers. He had this incredible grasp of the contemporary politics of the time. But it’s as though he knew exactly what was going to happen. He’s a very insightful writer.

Do you consider yourself a genre writer?

I started out as a classical genre writer. But in a way, I kind of developed my own genre. I have been interviewed by people who say, “The newspapers say you write spy novels or spy thrillers.” That isn’t really true. I don’t write spy novels. I write novels about spies. There is a difference there.

Did you expect to have such a cult following?

You can’t look for that. It’s a somewhat odd feeling for people to look to you that way. I don’t consider myself any kind of cult figure. But it’s true that people do that. I have a big fan base. Random House has told me, “We know they will buy your book every single time, and they will buy it early.” And that’s kind of how I survived at the beginning, and how I’ve prospered since. There are people who really, really like these books. What could be more flattering?

I consider myself a novelist of consolation. I consider what a novel was to me as a child: It was an escape. I could get away from the daily problems, whatever was going on, and escape to another time, another place, and be carried away. If that’s my role in the world, I could not be happier. I consider that a privilege.

2 thoughts on “Alan Furst Will Always Have Paris”

Mr. Furst’s first three novels are classics of their genre. Based on these novels Eric Ambler may be his only peer. The history is sound, as is the geography, politics and sociology. The writing is absorbing and captivating.

Then, it seems to me, Mr.Furst ran dry. His plots remained interesting, but less so as the stories rolled out. Dialogue became both repetitive and trite as did characters, even those making return appearances. The novels came from a novel writing machine, not a human author. To borrow a phrase, there is no soul there.

Mr. Furst may always have an unobtainable Paris. I will have “Night Soldiers”, “Dark Star’ and “The Polish Officer” on my bookshelves, always accessible and enjoyable. For that, Merci, Mr. Furst…

So many stories evolved from the WWII years; I was born in 1943, in the Oakland Naval Base hospital while my dad a Lieutenant JG from OTC, was stationed in The Philippines. He brought home these pea green storage chests carrying his uniforms, a big set of black binoculars, woolen white blankets with a dark blue stripe, white starched shirts, underwear and souvenirs from Manila. His ship the USS Eldorado (what a romantic name) was visited by himself, General Douglas MacArthur who, my dad said, looked like he’d walked right out of a movie. I am now reading Hans Fallada’s EVERY MAN DIES ALONE, in which he describes everyday life in Hitler Germany and the courage of a married couple who carried on their own small acts of treason against the Nazis. He had a years’ long problem with alcohol for which he was incarcerated in a Nazi insane asylum and later he died after the war and before he saw this movel published, of a morphine overdose. Very ssd.