Even today, in the shadows of the high-ceilinged, historic synagogue, it’s possible to imagine the weary, rough-hewn figures of hardy Jewish gold miners brushing the dust off their overalls as they enter the simple sanctuary. They drop into the cedar pews, thumb through their black prayer books and listen for the familiar melodies that remind them of their faraway homes.

More than a century and a half has passed since the 1851 gold rush created the booming Australian city of Ballarat, 70 miles inland from Melbourne. The huge strike drew prospectors from around the world, some directly from the California goldfields, including scores of adventurous Jewish miners and merchants. The gold is long gone, but here at the far fringes of the diaspora, on a recent Shabbat morning, the two dozen worshippers who sit shoulder to shoulder in the pews of Shearith Yisroel seem determined to live up to their synagogue’s name: “Remnant of Israel.”

The synagogue, the oldest on the Australian mainland, is now listed on the National Trust, the country’s leading conservation organization. Its sanctuary, built to seat 350, is a rectangular box laid out in traditional Orthodox style, with the bimah in the center of the room, facing the ark on the front wall. There are numerous clues to the congregation’s vintage. Flanking the ark are two gold-leaf tablets honoring Queen Victoria’s 1887 Jubilee, in Hebrew and in English. Other tablets memorialize members who were killed in the two world wars. A stained-glass window above the ark, said to have been taken from an Irish mansion, is thought to date from the time of Elizabeth I.

This morning, women slightly outnumber the men, but there’s a legitimate, Orthodox minyan for the service. In recent years, some concessions have been made to accommodate the shrinking, aging congregation, many of whose members are retired. Services are held only monthly and on holidays. Instead of the creaky second-floor gallery, the women now sit in first-floor pews, but on the opposite side of the sanctuary from the men, most of whom are in open-collared shirts and talesim. Much of the service consists of worshipers following along quietly in worn British Empire prayer books dating from 1890, donated by another congregation. Lay leader Max Lasky, retired from the textile industry, recites the prayers from the pulpit in a sweet, gentle, unhurried nusach (prayer melody). “I feel spiritually uplifted in this beautiful, 157-year-old shul and love the haimish, relaxed, traditional services,” Lasky says later. There are English readings by both men and women. Adding the English readings, he says, “creates a warm, welcoming community for those who don’t read Hebrew.”

True, it is not the liveliest of services. There are long stretches of silent prayer, disturbed only by the lazy buzzing of a slow, fat fly. Still, at times the congregation comes to life, suddenly rousing itself to join in familiar melodies. There are also poignant signs of fading memories. One member, who lived in Israel as a young man and had once been fluent in Hebrew, needs Lasky’s prompting for a Hebrew reading of a prayer for the State of Israel.

Things were very different once. The title of Shearith Yisroel’s 1979 paperback history, written by historian Newman Hirsch Rosenthal, is Formula for Survival: The Saga of the Ballarat Hebrew Congregation. And quite a colorful saga it is. Its website boasts that it was “Built on Gold,” a claim that melds hyperbole and wishful thinking: On two occasions, mining companies paid the congregation to dig for gold around the building—alas, without success.

On the whole, the Jews who streamed into Ballarat for the gold rush in the 1850s and 1860s were more likely to supply the shovels than to wield them. Yet there were some Jewish miners among the shopkeepers, tradesmen and gold buyers. Two years after the initial find, the first service was held in a hotel. A local newspaper observed, approvingly, that the fact that “the Children of Israel had made such an investment in Ballarat was by no means the least significant ‘sign of the times’ upon the great western goldfield.” According to the history, the cantor at High Holiday services on October 11, 1853, a native of Lemberg, Germany, davened in the traditional red shirt and high boots of a gold-mining “digger.”

Some things never change, at least when it comes to Jews and the struggle for social justice. Another German Jewish émigré, Teddy Thonen, was among 20 miners killed at Ballarat’s Eureka Stockade uprising in 1854. This first armed rebellion against the Australian central government is credited with paving the way for universal male suffrage. Both the president and a future president of the congregation helped draft the uprising’s key documents. A lawyer who was also a member of Shearith Yisroel stepped forward to help defend the surviving leaders—including another Jew, Jacob Sorenson from Scotland—who were charged with treason. All were acquitted.

The synagogue, on the corner of Princes and Barkly streets, was designed in the Renaissance Revival style by the English architect T. B. Campbell. At the 1861 opening, which packed the sanctuary and grounds with Jews and non-Jews alike, the Ballarat Times wrote that the building “is sufficiently tasteful without being ostentatious, and the interior is remarkable for the simplicity, perfectly in keeping with the object for which it was erected.”

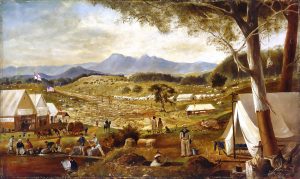

Gold mining at Ararat in Victoria, Australia, painted by English artist Edwin Roper in 1854.

Services began with a donated Torah from Melbourne, loaned with the proviso that the scroll would be returned if the congregation did not survive. At first, there was no need for concern, as the congregation grew and prospered, purchasing its own scroll in 1855. When the gold played out, many Jews stayed in Ballarat and helped build the young congregation. At its peak in the 1870s and 1880s, membership included 300 men, who may have represented 1,000 family members and required expansion of the women’s gallery. Three more Torahs were acquired in 1868 and 1869. During this time, there was a full-time rabbi and a full-time teacher for the afternoon Hebrew school, which had 60 students and fielded a cricket team. The thriving congregation established a Ballarat Jewish Philanthropic Society, a Hebrew Ladies Benevolent Society, a literary and debating society and even a volunteer fire brigade. In 1876, when a fourth Torah was acquired, a procession carried the scroll through the town.

“The early pioneers proved a sturdy and strong-willed group of visionaries who merged an intense Jewish consciousness with a passionate devotion to a country which gave them full citizenship and equality of opportunity,” Rosenthal wrote in his history. There was continued acceptance of the town’s Jews in the wider community, with Shearith Yisroel producing three Ballarat mayors.

Not that there weren’t some rough spots along the way. Early services were so boisterous, with people coming and going, that the doors had to be bolted while the Torah was being read. It was during this period that an uproar ensued when a woman in the second-floor gallery sang a solo during the service. Over the years, the community and the congregation have had their share of chronic schnorrers and crafty gonifs, one of whom pilfered the tzedakah box using a skeleton key.

The growth of the congregation, like much of Australia’s Jewish community, reflected the trajectory of the modern diaspora. Until the gold rush, only a few of the earliest Jewish arrivals to Australia made it to Ballarat—mostly criminals and prostitutes from England who arrived with the First Fleet of convict ships near Sydney and later Tasmania. But like many Jewish communities in the New World, the town provided a welcome haven for Jews fleeing periodic persecution and unrest elsewhere in the world. New members arrived from Germany in two groups, in the 1850s and 1860s, and again in the 1930s. At the turn of the 20th century, the congregation was reputed to be the most Orthodox in Australia. Even so, an influx of frum refugees from Eastern European pogroms in the 1880s and 1890s led to a split over religious practices in 1908, with the breakaway ultra-Orthodox meeting in a renovated warehouse. The breakup was not entirely bitter: If one group was short of a minyan needed to say kaddish or observe a yahrzeit, the other supplied the needed worshipers. A fifth Torah was acquired in 1914.

Shearith Yisroel’s decline in the early decades of the 20th century mirrored Ballarat’s economic fortunes. In the 1920s there were weeks when, for the first time, the by-now-reunited congregation was unable to muster a Shabbat minyan. By 1942, the congregation was hanging by a thread, with no rabbi and not enough worshipers for a minyan even on the holiday of Sukkot. Then, miraculously, the cavalry arrived. A contingent of U.S. Marines—including about 100 Jews—was temporarily based in Ballarat, training to fight the Japanese in the South Pacific. On the eve of Purim, they packed the synagogue’s pews, along with the locals, as Master Sergeant J. Green led the festival service.

With reports of the extermination camps in Europe filtering out, the chilling symbolism of the Purim service was clear to those in the pews. “The Megillah was read in circumstances that were moving in the extreme,” according to Formula for Survival. “The relevance of so much of the ancient story to the immediate moment was not lost on the large congregation,” some of whom would soon be in battle. To accommodate the servicemen, the synagogue added Friday evening services, and members opened their homes to the Yanks. The packed pews of those heady days reminded some of the older members of the congregation’s vital early years and, even after the Marines moved on, the new life spurred revival efforts. It was, the congregational history recalled, “evidence enough that the dogged perseverance and personal effort of the few which had kept it alive had not been in vain.”

But more challenges were to come. Like Jews in small towns in the American South, beginning in the 1950s, the community’s young people began leaving Ballarat for universities, then settling in larger coastal cities with greater economic opportunities and more vibrant Jewish communities. In recent decades, the historic synagogue has attracted more tourists, including non-Jews, than worshipers. Services for the tiny community were held only on the High Holidays. The last time there was a full house was in April 2011, when the congregation celebrated its sesquicentennial with a service of Thanksgiving.

About five years ago, Max Lasky and some other old-timers and newcomers came up with a new formula for survival, featuring monthly Shabbat and festival services. They were determined that their shul would not become an empty tourist attraction, or worse, one of Australia’s infamous padlocked or sold “ghost synagogues,” abandoned in smaller inland towns around the country. The congregation declined offers to align itself with a large Orthodox synagogue in Melbourne, which would have eased their financial burden, or with Chabad, which would have provided one of their circuit-riding “Outback rabbis.” Instead, they opted to go their own way. “We are a traditional independent shul,” says Lasky, one with a Modern Orthodox cast.

Still, survival remains daunting, according to Gary Mallin, who administers the congregation’s website. “If Yiddishkeit in the goldfields is not supported by visitors, members and volunteers who live outside its boundaries, it will die, slowly but surely.” On rare occasions, a visiting rabbi officiates as part of the monthly Shabbat services, and sometimes Torah readers come from Melbourne. Otherwise, all services are lay-led. So it’s up to Lasky to coordinate the services, which he does without complaint. “I enjoy this community work and see it as a great mitzvah,” he says.

Interior of the sanctuary, Ballarat Synagogue.

So these days, members and guests are invited to speak at services—as I was—in hopes of luring additional friends and family. The congregational leaders also encourage unaffiliated (or cash-strapped) Melbourne Jews and former Ballarat residents to get out of the city and attend High Holiday services—which in the Southern Hemisphere usually come in the spring. There are plenty of seats, offered without charge or required membership. Interested non-Jews are also welcome. Among those attending on the morning I was there was an Irish Catholic nun who participates in an international Torah study group hosted on Skype by a Colorado rabbi. In 2016, the congregation built its first sukkah in 80 years. There are now 110 names on the membership rolls.

I was so drawn to the tiny congregation and its jewel-box sanctuary in 2017 that when my wife and I returned to Australia last fall, we decided to accept Max Lasky’s invitation from the previous year and attend Yom Kippur morning services. We were greeted as old friends.

This year in the Southern Hemisphere, it is late spring, sunny but still crisp. Inside the sanctuary, the only defenses against the chill are several small, malfunctioning space heaters. Contrary to Orthodox practice, a few of the women wear talesim, but as shawls for warmth rather than ritual. Scattered on the pews are matched and mismatched pillows used to cushion the unpadded wooden seats. There are 15 men and 9 women, slightly more than at the Shabbat service the year before.

Lasky, dressed in a dark suit and Sir Isaac Newton–brand running shoes, is back in the pulpit, speeding through the four-hour service as best he can. This time, he is supported by a stronger, humming undertone of prayer from the larger crowd. There is still a good deal of liturgical spontaneity. The presence of an Israeli couple adds some fluent Hebrew readings to the mix. When the shul’s five Torahs are removed from the ark, Nathan Mond, an internet radio broadcaster, assists in the chanting before the open ark. I was given both an aliyah and the honor of opening the ark.

Near the end of the service, John Abraham, the congregation’s president, whose great-grandfather came to Ballarat in the early 1850s, gives a short talk, reviewing the shul’s 165-year history. As an example of continuity, he talks about how he has restored the synagogue’s small original ark and made it into a bookcase now residing at the back of the sanctuary. Members scatter around 2:30 p.m., vowing to return for Ne’illah and a communal break-the-fast in the separate social hall and kitchen behind the sanctuary.

Mark I. Pinsky is an Orlando-based journalist who writes about diaspora communities around the world.