by Irvin Ungar and Allison Claire Chang

This October marks the 50th anniversary of the then-controversial Nostra Aetate [Latin: In Our Time], the Second Vatican Council’s declaration on the Catholic Church’s relationship to non-Christian religions. Issued a generation after World War II and the Holocaust, the declaration devotes one-third of its text to Judaism, rejecting once and for all the belief that the Jews bear collective guilt for the death of Jesus, and condemning anti-Semitism at any time, by anyone. Nostra Aetate signaled the beginning of the Church’s modern dialogue with Jews and Judaism, as well as decades of soul-searching to understand how and why Christian Europe largely stood by while six million Jews were systematically slaughtered.

Reckoning with the darkest moments of the past—a process the Germans call Vergangenheitsbewältigung—is painful and slow for an individual, let alone a massive institution with 2,000 years of history. Yet by most accounts the Church has made progress in the past 50 years. The Good Friday liturgy has been updated, more than once, in an attempt to remove anti-Semitic wording. In 1979 Pope John Paul II visited Auschwitz, the first pontiff to visit a Nazi death camp. In 1987 the National Catholic Center for Holocaust Education (NCCHE) at Seton Hill—the first of many such centers at Catholic institutions—was founded to promote the historical and religious study of the Shoah. In 1998 the Vatican issued a formal apology for the Church’s inaction during the Holocaust. In 2005, for his first official visit to a non-Christian religious site, Pope Benedict XVI chose a synagogue in Cologne, Germany; three years later, he became the first pope to visit a synagogue in the United States. And on a more personal level, Pope Francis made waves in 2013 when he revealed in an official interview that his favorite painting is Marc Chagall’s White Crucifixion (1938).

White Crucifixion is a challenging piece, regardless of one’s religious background or beliefs. Jewish artist Marc Chagall was living in southern France when he learned of Kristallnacht, the state-sanctioned, anti-Semitic violence that rocked Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland in November 1938. In response, Chagall painted a canvas placing Jesus on the cross—a figure well understood to symbolize innocent suffering—at the center of several scenes of the present-day destruction of Jewish lives and property. Chagall fluidly mixes Jewish and Christian imagery: his Jesus is a distinctly Jewish martyr, wearing a striped prayer shawl around his waist and a head cloth instead of his traditional crown of thorns. Rather than the Virgin Mary and disciple John, Jewish patriarchs and a matriarch gather at the cross to keep watch, hands raised in despair at the unfolding injustice. The work can be viewed as a meditation on the suffering of Jews in the mid-20th century and throughout history, but especially at the hands of their Christian neighbors. (After all, nearly two millennia of Church-sponsored anti-Semitism provided a strong foundation for National Socialism’s racist policies.) That the current Pope is not only familiar with White Crucifixion but actually embraces it shows a remarkable openness to Jewish art that makes strong claims on Christian moral conscience.

As if to affirm this possibility, Catholic leaders and educators soon will grapple with another challenging Jewish artist from WWII. Every three years the NCCHE gathers educators from around the globe for the Ethel LeFrak Holocaust Education Conference, which aims to discuss the causes of anti-Semitism and the Holocaust as well as to suggest appropriate curricular responses. This year’s LeFrak conference—happening on October 25-27, and the first since the appointment of Pope Francis—includes, alongside the usual lectures, an exhibition of the work of Polish-Jewish artist Arthur Szyk (1894-1951). A contemporary of Chagall, Szyk (pronounced “shick“) was largely forgotten in the decades immediately following WWII, but may now be ideally positioned to serve as bridge for continuing Jewish-Christian dialogue on the Holocaust and beyond.

Before he was a famous artist and illustrator, Szyk was a soldier and propagandist in World War I. After spending the 1920s in France, and much of the 1930s in Poland and England, Szyk anticipated that Europe’s rising tide of anti-Semitism would result in disaster for the Jewish people. He immigrated to the United States in 1940, his extended family staying behind in his hometown of Łódź, Poland. (Szyk’s elderly mother and brother were later deported from the Łódź ghetto and murdered in the Chelmno killing center.) By the time Szyk reached the United States, he had shifted his career to serve full-time as a “soldier in art” for democracy and freedom, producing anti-Nazi political caricature for mass publication in American newspapers and magazines. He also fought to keep the persecution of the Jews in the public eye, as the unfolding calamity garnered relatively little media attention. Part of his strategy to influence public opinion and to induce decisive action against the genocidal Nazis was to portray nonintervention as the moral equivalent of committing the crime itself.

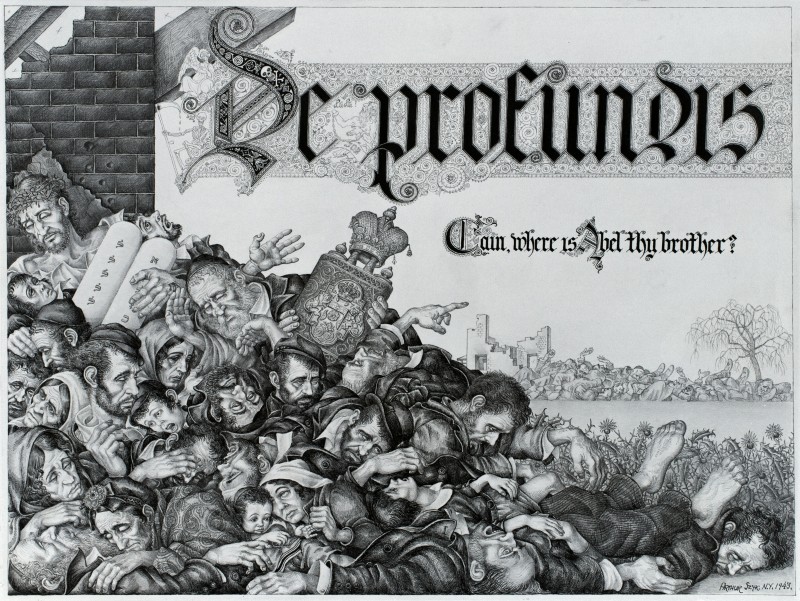

Consider Szyk’s standout work: De Profundis: Cain, Where is Abel Thy Brother? (1943). It could be said that De Profundis is the anti-Guernica. Picasso overwhelms the viewer with a giant landscape of abstracted death and destruction, where suffering has no apparent cause or resolution (and perhaps no meaning). Szyk instead draws the viewer into an all-too-human, of-the-moment catastrophe that is unsparing in detail and unforgiving in its moral judgment. Though he had not yet seen a photograph of the ghettos or camps in Europe, Szyk (rightly) assumed the worst. An accomplished miniaturist, his pen and ink rendering measures about the size of a ledger sheet, small enough to be held in one’s hands, like a first-person dispatch from the field. The black and white composition is dominated by a mass of dead and dying Jews, young and old, rich and poor, each with a distinct face and expression.

The incline of twisted bodies leads the eye first to an elderly man clutching the Torah scroll and then to the figure of Jesus, who cradles the tablets of the Ten Commandments in one arm and a dead boy in the other. (Like Chagall, Szyk had no qualms in appropriating Christian symbolism to make his point.) Another rubble-strewn killing field is visible in the background, indicating that devastation continues beyond what the eye can see.

At the top of the drawing, the words “De Profundis” (Latin for “out of the depths,” the opening words of Psalm 130) appear in gothic calligraphy. In a nod to the Christian tradition of manuscript illumination, the phrase is richly ornamented with delicate filigree and three lightly drawn figures: an angel, a skeletal figure with a scythe, and the suffering Job, who cries, “Eli Eli [lama sabachthani],” my God, my God, why have you forsaken me? (Psalm 22:1)—words that Jesus cried out during his painful crucifixion.

In smaller calligraphy just below is yet another Bible verse, Genesis 4:9: “Cain, where is Abel thy brother?” the question God posed after Cain committed the world’s first murder. Szyk leaves it to the viewer to remember and consider Cain’s callous answer, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” The outstretched hand of one lifeless man—in a gesture deliberately reminiscent of Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam in the Sistine Chapel—points toward the “C” of Cain in silent accusation. Within the capital “C” is a Nazi swastika, and within the “A” of Abel a Star of David, clearly identifying both the perpetrators and victims.

This provocative work was sponsored by the Textbook Commission (organized by the Protestant Digest, Inc.), a group that sought to expunge anti-Semitism from American textbooks. De Profundis illustrated the Commission’s full-page advertisement in the Chicago Sun in February 1943, within three months of the U.S. State Department’s official confirmation of the Nazis’ concerted efforts to annihilate the Jews of Europe. Entitled “The Living Voice of the Dead,” the ad stated, in part: “Out of the depths they speak…nor man nor committee nor organized ‘hush hush’ can stop them…2,000,000 sensitive human beings tortured, starved, butchered in an orgy of hate reaped by Hitler but sown in the very soil of Christian civilization, sown in the texts of intolerance.”

It is striking that American Christians turned to a Jewish artist to spur the collective conscience of their brothers and sisters in 1943, going so far as to suggest their complicity in one of the century’s greatest tragedies. Perhaps Szyk, as a popular artist and a religious outsider, was best positioned to speak hard truths in that historical moment. That those truths can move us some 70 years later is a testament to the power of art. Whether Szyk’s De Profundis remains within the sphere of Holocaust curriculum or goes mainstream like the film Schindler’s List, prominently exhibiting his work at a Catholic institution shows much has changed since the end of WWII. Barring new traumas, the next 50 years of Catholic-Jewish relations will extend the meaningful dialogue begun with Nostra Aetate, and create a shared future marked by mutual respect and responsibility rather than mistrust and pain.

—-

Irvin Ungar is curator of The Arthur Szyk Society (www.szyk.org). He will speak about Arthur Szyk at the Ethel LeFrak Holocaust Education Conference at the National Catholic Center for Holocaust Education on October 26, 2015. His essay “Arthur Szyk: Artist for Freedom” was recently published in Washington’s Rebuke to Bigotry: Reflections on Our First President’s Famous 1790 Letter to the Hebrew Congregation In Newport, Rhode Island (Facing History and Ourselves, 2015). Ungar is an antiquarian bookseller and former pulpit rabbi.

Allison Claire Chang is a Bay Area-based writer and editor. She is managing editor and executive vice president of The Arthur Szyk Society (www.szyk.org) and author of Heroes of Ancient Israel: The Playing Card Art of Arthur Szyk (Historicana, 2011).

One thought on “Nostra Aetate at 50: Jewish Art, Christian Conscience”