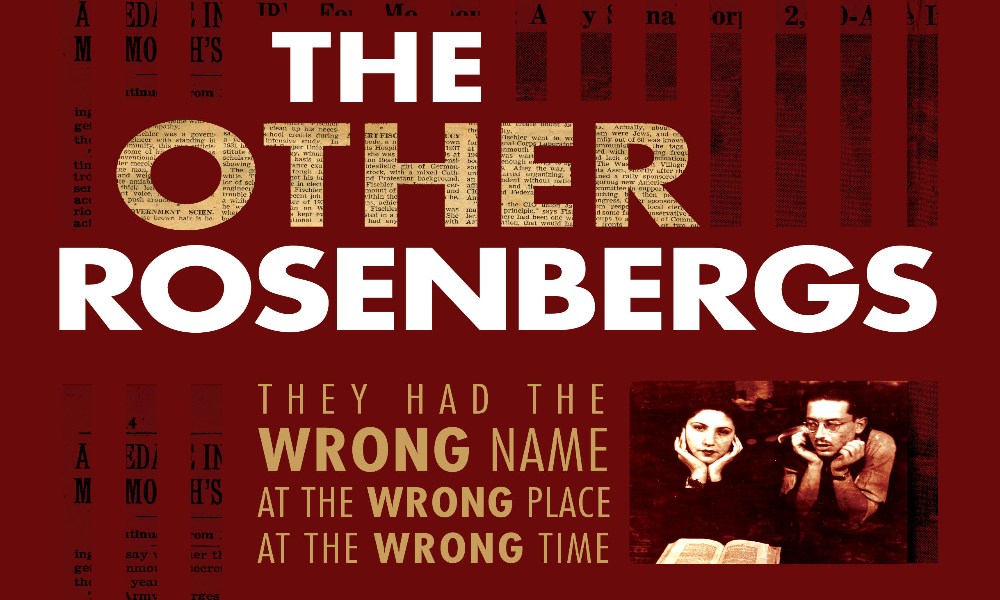

They Had The Wrong Name At The Wrong Place At The Wrong Time

An investigation into discrimination against Jews who worked for the U.S. Army Corps at Fort Monmouth, NJ in the wake of Julius Rosenberg’s arrest.

It was September 14, 1950, and the American hunt for communist infiltrators was at its peak. A little more than a year before, the Soviet Union had detonated its first atom bomb, which was built using information supplied by spies. Two months earlier, Julius Rosenberg, a young radar inspector for the U.S. Army Signal Corps, had been arrested for passing secrets to the USSR. Milton Rosenberg—a civilian electronic radio engineer with high-level clearance and a spotless record—was in his office at the short-range navigation unit of Watson Laboratory, just a few miles from Signal Corps’ headquarters at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, a sprawling hub of military communications research.

Milton Rosenberg was not related to Julius Rosenberg, whom he had never met. The child of struggling Orthodox Jews who had fled Eastern Europe, he was a staunch anti-communist, a Republican and a civilian Air Force employee since 1941. So he was shocked, when an Air Force officer entered his office and told him that he was being dismissed—without pay—as a security threat. His dismissal, based on Executive Order 9835, the loyalty program President Harry Truman authorized in 1947, was effective immediately. Rosenberg was escorted from the building to his car.

By the time he arrived at his apartment in nearby Asbury Park, he was ashen, says his widow, Eva Rosenberg, now 93 and living near Cleveland, Ohio. “We had young children,” she recalls. “Paula was seven and Stuart was four. Karen was an infant.” Her mother cried, recalls her daughter Paula Hecker, who now lives in Tucson, Arizona. “I remember a lot of hysteria.”

Rosenberg was given no explanation for his dismissal. “For 30 days we didn’t know why,” says Eva Rosenberg. On October 12 he received a letter from the Central Loyalty-Security Board, detailing the charges:

1. “On all the evidence, reasonable grounds exist for the belief that your immediate removal is warranted by the demands of national security. The evidence indicates that: During the period from 1945 to May 1950, at or near Washington Village, Asbury Park, NJ, you associated to a close and habitual degree with Louis Kaplan, who, evidence in the files of the Air Force indicates, has been active in the affairs of the Civil Rights Congress and of the Communist Party. The Civil Rights Congress has been designated by the Attorney General of the United States as communist. The Communist Party has been designated by the Attorney General of the United States as communist, subversive and seeking to alter the form of government of the United States by unconstitutional means.

2. The foregoing reported association, and all the evidence related thereto, indicates that you have been and are a member, close affiliate or sympathetic associate to the Communist Party.”

Until earlier that year, Milton Rosenberg and his family had lived on one end of a two-block-long garden apartment project called Washington Village. The aforementioned Louis Kaplan—known for writing “communist-sympathetic” letters to the editor of the local newspaper, The Asbury Park Evening Press—lived at the other end. The Rosenbergs had never associated socially or politically with Kaplan, a stout, balding man who had left his job at the Fort Monmouth Standards Agency in 1947. He had become a chicken farmer, and his wife Ruth sold eggs to neighbors.

Executive Order 9835 protected the confidentiality of informants, so Rosenberg was in the dark as to the source of the information that had led to his dismissal, but he did have a right to an administrative hearing before the loyalty board. Sidney Meistrich, a friend, prominent local attorney and a leader at Asbury Park’s Congregation Sons of Israel, the Orthodox synagogue where the Rosenbergs’ two older children attended religious school, counseled Rosenberg to hire a non-Jewish lawyer.

No longer receiving paychecks, the family of five struggled financially. Eva Rosenberg, then a stay-at-home mother, went to work. “I did bookkeeping at fish restaurants on the boardwalk,” she says, referring to Asbury Park’s beachfront resort area. “I’d get a big fish meal and could bring fish home. And my sister’s husband came by with cash every few weeks.”

Worse than their financial woes was the ostracism. “People who knew me and knew we weren’t communists would refuse to talk with me and crossed the street when they saw me,” says Eva Rosenberg. “It was very hurtful.” She says her husband never got over the way friends turned their backs. “He was very bitter at the people who weren’t our friends during this period of time.”

Anxiety pervaded their lives. Until her husband’s suspension, Eva Rosenberg had been nursing Karen but within days lost her milk. Dr. Mark Ellenson, the local pediatrician, blamed it on stress.

That same September day—50 minutes apart, to be exact—an Air Force officer visited the office of another Signal Corps civilian engineer at the Watson Lab and suspended him immediately as a security risk. His name, too, was Rosenberg: Sidney Rosenberg.

Like Milton Rosenberg, Sidney Rosenberg did not know Julius Rosenberg, was not a communist and had been raised as an Orthodox Jew in New York City. A biologist, he had recently completed four years of night school at New York University, earning an M.A. in engineering at the behest of the Air Force. Sidney Rosenberg—who lived with his wife Claire and their children, Barbara and Paul, in the nearby town of Red Bank—was also not informed what the charges against him were.

Thirty days later, Sidney Rosenberg received a letter charging him with association with the same Louis Kaplan. Again, like Milton Rosenberg, Sidney Rosenberg did not know Kaplan well and had until earlier that year resided in the same Asbury Park housing project, Washington Village. Both their wives had, out of pity, sometimes purchased eggs from Ruth Kaplan.

As the two Rosenbergs were to discover in separate administrative hearings before the Loyalty-Security Board, the charges against them were interconnected. Milton Rosenberg’s hearing came first on November 28. With his wife and attorney William J. O’Hagan by his side, he listened to the detailed charges read by the examiner in front of the four-person board, three of them civilians and one an Air Force lieutenant colonel:

“Our information is that you, Milton Rosenberg, and Louis Kaplan were seen through an open window of the apartment of Sidney Rosenberg at 16 Washington Place…and that both you and Sidney Rosenberg were talking with Louis Kaplan about once a week for approximately six weeks prior to May 1950.”

“I swear by all that is holy that it is incorrect,” Milton Rosenberg answered when asked if he had ever been in an apartment together with Sidney Rosenberg and Louis Kaplan. He explained that he had been inside the Kaplans’ apartment only once, after their seven-year-old son Howard had thrown a rock at the Rosenberg family’s cream-colored Mercury on October 21, 1948, shattering the windshield. He had gone to the boy’s home to ask his father to pay for the damage but Kaplan, he said, had refused. Rosenberg also recalled being present at a 1946 party honoring Kaplan, a co-recipient of one of the Standards Agency’s highest civilian awards.

When asked, Milton Rosenberg denied he was related to Julius Rosenberg, was a communist or a member of any communist-related organization. He belonged to only two groups: B’nai B’rith Shore Lodge 1685 and the Institute of Radio Engineers. “Communism is atheism and atheism and Orthodox religion, or any religion, just don’t mix,” he testified. He was also questioned about his presence at a NAACP rally at which communists were said to have been in attendance.

After coworkers, friends and family members who had come as character witnesses spoke on his behalf, the informant was called to testify. He was Newell C. Jardine, age 52, the maintenance man in Washington Village between October 1944 and October 1945 until he had been hired as a plumber at Fort Monmouth and become a tenant of Washington Village. Jardine had lived in the apartment next door to Sidney Rosenberg and his family. “We hardly knew him,” recalls Eva Rosenberg.

The examiner asked Jardine if it was true that he had told the FBI that, “While walking your dog at 11 p.m. in the evening you observed Louis Kaplan [and] Milton Rosenberg, through an open window of the apartment of Sidney Rosenberg.” Jardine replied: “No, I can’t say that I did.” Although he had retracted his accusation, the examiner and board members questioned him for a prolonged period, before then calling Eva Rosenberg to testify.

She was told that the FBI had information that showed she might be connected to the Communist Party, noting that in 1942 a woman with the same name had signed a Communist Party nominating petition in New York. Eva Rosenberg testified that that was not her and that she had not lived in New York in 1942, but with her husband in New Jersey. “I didn’t know they had an FBI file on me until it came out in the trial,” says Rosenberg, who was terrified that the board would learn that her father and aunts were socialists. “They kept thinking I was 34—I was 30—and kept calling me Ethel.”

Sidney Rosenberg’s hearing followed Milton Rosenberg’s. But the second Rosenberg was less fortunate: Newell Jardine did not retract his previous statement and insisted that he had seen Louis Kaplan in Sidney Rosenberg’s apartment. “They [were] around the table in the kitchen and they were over the table,” said Jardine when asked for a description of what he had seen. “I don’t know what was on the table. They may have been studying for school.” Jardine said he knew of Kaplan’s communist sympathies because his daughter, who had worked as a babysitter for the Kaplans, said she had seen communist literature in their apartment.

Jardine also testified that the FBI had come to his home in 1948 and 1949 several times to inquire about Louis Kaplan’s acquaintances. While he had observed Louis Kaplan in Sidney Rosenberg’s apartment over a several-year period, he hadn’t reported it because investigators hadn’t specifically asked about Sidney Rosenberg until 1950.

During his hearing, Sidney Rosenberg explained that the man in the kitchen wasn’t Louis Kaplan but a fellow student in NYU’s master’s program. “We would study electric wave magnetism together,” says Rosenberg, now 97 and living in Sunnyvale, California. “He was helping me with the math. I was a biologist. The guy looked like Kaplan; he was about the same size.”

After the hearings the two families waited. Four long months later, on March 26, 1951, Milton Rosenberg was cleared and immediately reinstated into the Signal Corps with back pay. “After we were cleared some friends came back,” says Eva Rosenberg. “They said how badly they felt. Everyone was afraid for their jobs.” Other friends never returned.

Within a few months, he was transferred with his unit to Griffiss Air Force Base in Rome, New York. The family moved to a house in Utica, from which Milton Rosenberg commuted. “We didn’t want to live in another apartment project where everyone worked for the government,” recalls his widow.

“Milt grieved about what had happened,” she says. “He was very hurt and had a lot of hard feelings, but he liked his work.”

Sidney Rosenberg’s case took longer to resolve. When he was cleared in June of 1951, he too was transferred to Rome. The family settled there, in the hopes of beginning their lives anew. But unfortunately for both Rosenbergs, President Dwight Eisenhower’s Executive Order 10450 was still to come.

Both Eva Rosenberg and Sidney Rosenberg are convinced that the surname Rosenberg was a red flag for investigators. “They got everyone with the name Rosenberg,” says Sidney Rosenberg angrily. “I had no relation of any kind to Julius or Ethel Rosenberg. That son of a gun passed secrets. Of course I didn’t know him.”

Other Jewish names also attracted unwanted attention, and in fact, any Jewish name was a liability. “Names were a category, just like whoever went to City College in New York or studied in a physics class with Julius Rosenberg was suspected,” says Donald Ritchie, historian of the U.S. Senate, who edited the closed hearing transcripts of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations.

Kaplan was another problematic name at the Signal Corps. This was due to the same Louis Kaplan who had lived in Washington Village and worked at the Standards Agency. Kaplan, who was not suspected of being a spy and was never convicted of any crime, invoked the Fifth Amendment when asked during the 1953 McCarthy hearings about possible communist activities. While Kaplan was not the only former Fort Monmouth employee to plead the Fifth at the hearings—others who refused to testify about possible communist activities were Albert Socol and Marcel Ullman—Kaplan’s name was the most common.

This was unfortunate for another Louis Kaplan, a high-level scientist in the Thermionics Unit at the Camp Evans Signal Laboratories, a facility a few miles south of Fort Monmouth. From 1942 on, he was plagued by mix-ups with the Louis Kaplan at the Standards Agency. At first, it was paychecks, then bank accounts. “His wife’s name was Ruth, the same name as my wife, and he had two boys and I had two girls,” recalls Kaplan, now 94 and living in South Orange, New Jersey. “Down the line I began to see there was a problem with this guy…security people were after me and I was being investigated until I was blue in the face. We had seven-and-a-half years of hell.”

Kaplan was fired in 1953 and testified a week later before the Senate subcommittee, during which he was questioned by chief counsel Roy Cohn about his relationship to the other Louis Kaplan. Kaplan, whose father had spent his career fighting communist infiltration into the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, was cleared a week later. To avoid further confusion, he started using his middle name. “I arrived at Fort Monmouth as Louis Kaplan and left Louis Leo Kaplan. I’ve been Leo ever since.”

Another man confused with Louis Kaplan was Jacob Kaplan, an assistant branch chief in the Countermeasures Branch at Camp Evans. During Jacob Kaplan’s testimony before the Senate subcommittee on October 30, 1953, Roy Cohn asked: “You have never been known as Louie Kaplan?” to which Jacob Kaplan replied “No,” and Cohn retorted, “Maybe they are suspending everyone with the name Kaplan.”

The pursuit of scientists with names such as Rosenberg and Kaplan was ironic since so many of those names were American inventions. “Rosenberg wasn’t even our real name,” says Sidney Rosenberg. “When my father came to Ellis Island he either changed it or someone else did. It was Gorcyzski. Some people with this name changed it to Goren or to Green. When I told the FBI investigators this, they interviewed Mr. Green who ran the cafeteria.”

Eva and Milton’s youngest daughter, Karen Rosenberg, tells a similar story: “After all this, of course, Rosenberg is not really our name. My grandfather Samuel Rosenberg bought somebody else’s papers in the old country.” The coincidence, she says, is that “our name was Kaplowitz, that is, we were Kaplans.”

Jews, by any name, were not particularly welcome in Monmouth County, New Jersey, before World War II. Located about 60 miles south of New York City, the county was rural but for the string of resort towns along the Atlantic Ocean. Some Jewish families resided in these shore communities despite Ku Klux Klan activities in the 1920s and German-American Bund rallies in the 1930s. As late as 1948, a 12-foot cross was burned on the newly purchased home of Leroy Hutton, described in The New York Post as a “Bronx Negro,” who was an engineer at a Fort Monmouth laboratory.

When World War II broke out, the county’s transformation to a New York City suburb began, thanks in part to Fort Monmouth, which ballooned from 150 to 14,000 employees. To fill new positions in military laboratories, the government hired Jews and blacks, drawn mostly from New York City. Most were young Jewish scientists who had difficulty finding jobs in their field. “At the onset of World War II, most private laboratories like Bell Labs didn’t hire Jews or had quotas,” says Jean Klerman, a former county librarian and a board member of the Jewish Heritage Museum of Monmouth County. “All the bright scientists came.”

The large wave of Jews fanned anti-Semitism. One focal point was Washington Village. Still standing today, the 64-unit apartment project was constructed in 1943 by the federal government for low-income residents, but due to the World War II housing shortage, was opened to Signal Corps employees. A newspaper report from the time says that half of Washington Village’s apartments were occupied by Jewish families.

Locals, including returning veterans, were incensed that federal employees who earned more than the income guidelines were allowed to settle in Washington Village. Their furor was whipped up by Conde McGinley, the publisher of a widely distributed local anti-communist and anti-Semitic newspaper called Think. McGinley’s paper charged that Washington Village and its tenants’ association were “Communistic and Jewish,” according to a January 8, 1951, article in The New York Post. (McGinley became nationally known in 1950 for his unsuccessful fight to derail the nomination of Anna Rosenberg, a New York attorney whom President Truman had nominated for Assistant Secretary of Defense and whose husband was named Julius Rosenberg, no relation to the spy.)

Tensions erupted in Washington Village in the late 1940s, when some residents and management tried unsuccessfully to evict Fort Monmouth employees. Around the same time, the FBI began to investigate many of the Fort Monmouth Jews living at Washington Village, who could be fired if “reasonable doubt” existed concerning their loyalty under Executive Order 9835.

“The natural conflict between the old residents and newcomers was exacerbated by religion,” says Klerman, who interviewed many of those involved. “The conflict was between the local uneducated Christians and the Jewish newcomers.”

“It was a very conservative area; it was a very explosive situation, you had a civilian security force that was very anti-Semitic,” says David Oshinsky, Pulitzer-Prize winning author of A Conspiracy So Immense: The World of Joe McCarthy. “They were picking these people off.” Given the fact that many of the Jewish scientists had attended City College or had associated in some way with communists or with someone who had been associated with them in their youth, “there was enough superficial evidence there to light a bonfire.”

With superficial evidence ripe for the picking, many were willing to pick it. According to Klerman, Ira Katchen—a local attorney who later represented many of the scientists called to testify before McCarthy—blamed the head of security at Fort Monmouth from 1940 to 1953. “Katchen said he was a real anti-Semite,” says Klerman. “He had his spies all over.”

That was Andrew J. Reid, who was described by one of the men he investigated as “a local cop from Eatontown” who knew nothing “about the scientific problems we faced.” Reid’s suspicions were shared by Signal Corps Intelligence Agency officers, army intelligence investigators and an active network of local anti-communists.

From 1946 on, Reid and others investigated scores of Signal Corps employees and were astounded when the local loyalty boards determined that most were loyal, including a few who had committed security breaches. As a result of these exonerations, those employees that had been dismissed were reinstated. Others, such as Milton Rosenberg—whose FBI file dates to 1948—were not dismissed at the time.

Until McCarthy drew national attention to Fort Monmouth, little appeared in local newspapers during this period. “The press didn’t cover it,” said the late Doris Raffelovich, a longtime local reporter. “And nobody talked about it. They were all ashamed.”

Some of these early Signal Corps investigations took on new life in 1950 when the Soviets detonated the atom bomb that they built based on information supplied by communist spies in the U.S. One of these spies was Klaus Fuchs, a German theoretical physicist who was convicted that year of providing the Russians with documents from the Manhattan Project during and shortly after World War II. Fuchs, who had worked at Los Alamos, fingered another Los Alamos nuclear physicist, David Greenglass, who in turn led investigators to his brother-in-law Julius Rosenberg. The news of Rosenberg’s involvement led to wild speculation about a possible Rosenberg spy ring at Fort Monmouth, reigniting interest in those who had already been investigated even if they had been cleared.

In 1951, Major General Kirke B. Lawton took over as Fort Monmouth’s commander. He was described as being “obsessed” with security regulations and, like Reid, he was disturbed that scientists who had been suspected of being dangerous to the U.S. security had been reinstated with the Army’s stamp of approval. So in 1953, Lawton ignored the Army’s upper echelons, who were concerned that McCarthy was overstepping his authority, and secretly alerted McCarthy’s Senate subcommittee to the possibility of communist subversion at his facility, according to Rebecca R. Raines, an Army historian and author of the paper, “The Cold War Comes to Fort Monmouth: Senator Joseph R. McCarthy and the Search for Spies in the Signal Corps.”

McCarthy was on his honeymoon when Roy Cohn informed him of Lawton’s call. He rushed back to Washington to launch his investigation on August 31, 1953. It should come as a surprise that McCarthy was interested in the Signal Corps, says Oshinsky. “You might think this investigation came out of thin air but that would be a mistake. What you can’t whitewash was that there were security breaches at Monmouth. During World War II there was no security in place; it was just assumed that people were loyal. The hiring of someone like Julius Rosenberg was an enormous security breach.”

When the Jews of Fort Monmouth began making national headlines, the national Jewish community kept its distance, says Harry Green, an attorney for some of McCarthy’s victims in an article that appeared in the 1950s in The Asbury Park Evening Press. “I have been shocked,” he says, “by the complete apathy, the hush-hush attitude and atmosphere with which we have been received at the top level.” He singles out for criticism the American Jewish Congress, the American Jewish Committee and B’nai B’rith’s Anti-Defamation League. Green also criticizes local Jewish groups for not coming to the defense of Signal Corps employees. He calls the Fort Monmouth situation, “The American Dreyfus case except that here there are 41 Jews being sacrificed instead of one.”

Fortunately for Milton and Sidney Rosenberg, they escaped the attentions of McCarthy’s investigators. They did not, however, avoid the new round of investigations authorized by the April 1953 Executive Order 10450, which revoked Truman’s Executive Order 9835, dismantled the loyalty boards and entrusted the entire investigatory process to the FBI.

During 1953 and 1954, both men were fully reinvestigated by the FBI for the same charges. According to Milton Rosenberg’s FBI file, various informants re-interviewed by FBI agents at this time said they had assumed all the Jews in Washington Village were friendly with one another and that Milton Rosenberg was friendly with Louis Kaplan because the two were of the same faith.

After anxiously awaiting yet another decision, the men were once again cleared and could begin to put the episode behind them. By then, the Cold War was thawing and fears of communist infiltration were beginning to fade. Soviet leader Joseph Stalin had died in 1953, raising hopes that U.S.-Soviet relations might improve. McCarthy’s confrontation with the Army and the televising of the so-called Army-McCarthy hearings—where the general public got to see the volatile senator in action for the first time—led to his censure in the Senate in December 1954. On July 21, 1954, Fort Monmouth’s General Lawton was ordered to Walter Reed Hospital for a “medical check up” and then forced to retire. Andrew Reid stepped down as security chief and the internal investigations evaporated. When McCarthy died at age 48 in 1957, he was unaware of the actual evidence against two real Julius Rosenberg co-conspirators who had fled to the USSR: Alfred Sarant and Joel Barr.

Many wrongly accused struggled to put their lives back together. In 1957, Sidney Rosenberg left the government, moving to Sunnyvale, California to take a job at Lockheed Martin where he worked on reconnaissance satellite guidance systems. After a year as a chicken farmer, Louis Kaplan became a writer for The Asbury Park Evening Press. Milton Rosenberg and Louis Leo Kaplan went on to have fulfilling government careers.

But the innocent people targeted by investigators were scarred. “This was the worst time in my life,” says Sidney Roseberg, now the oldest member of Temple Emanu-El in San Jose, California, where for more than four decades, he has chanted the Rosh Hashanah service in Hebrew for the congregation. Fearful of unwanted attention and possible retribution, he remains reluctant at first to talk about what happened to him.

Eva Rosenberg, who became a bat mitzvah at age 91, believes it is important to let the world know, although she often expresses concern that doing so might lead the government to take away her husband’s pension and her health insurance.

Milton and Eva Rosenberg’s daughters believe their family has been deeply affected. Their parents didn’t speak about what happened for years and didn’t tell their daughter Karen until 1968, when she was 18. “My parents lived under a halo of shame,” says Karen Rosenberg, now a social worker in Ohio. “They didn’t want to lose their friends again. They had been shunned in Washington Village. The whole affair was shrouded in secrecy. I couldn’t understand it at the time. I couldn’t understand anyone trying to hide their politics. But my mom kept saying over and over again that they didn’t want to lose their community. Now that I am older I understand that. I see how the trauma is still in her being.

“Such a traumatic experience never really fully goes away,” says Karen Rosenberg, “especially when it is not openly discussed.”

Click here to read a special report on anti-Muslim discrimination in post 9/11 America

This project was supported by the Fund for Investigative Journalism

the communist, socialist and american labor parties were Not illegal … they were even on the ballot

Russia was our ally during the war, and almost single handedly defeated the Axis powers (and as an interesting piece of history INCLUDED the Ukraine …)