To & Fro

By Leah Hager Cohen

Bellevue Literary Press, 416 pp

Interview by Debby Waldman

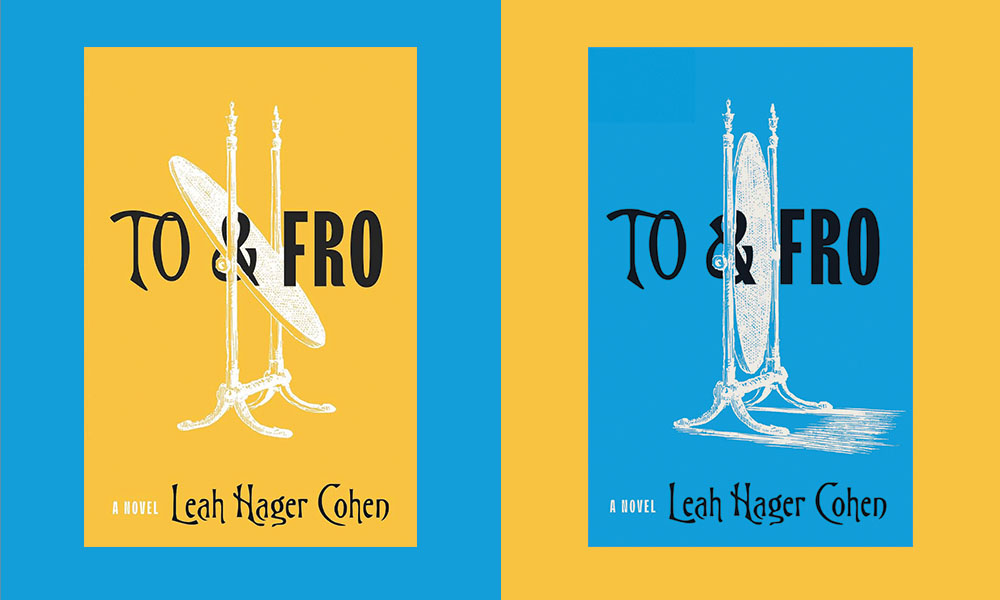

The two stories that make up Leah Hager Cohen’s captivating new novel, To & Fro, meet halfway through the book with an explanation—“Two Beginnings and No End”—and an invitation: “Flip this book.” If you started with To, you flip to read Fro. If you started with Fro, you flip to read To.

In less skilled hands, a novel with no clear beginning and end, which readers must flip to complete, could seem like a gimmick. But To and Fro is a gem: a captivating story about two 12-year-old girls, living very different lives, on separate but parallel quests to explore some of life’s big questions. Among them: What is family, how do you combat loneliness, and what does it mean to belong to a place and a people?

Ani (pronounced ah-KNEE, like “I” in Hebrew), the protagonist in To, is searching for the Captain, the leader of one of the many communities she will temporarily call home as she travels an unidentified countryside in an unidentified era with nothing but a kitten for company. Her mother is dead, and she is not welcome in the home her father shares with his favored wife. In her travels, Ani stumbles on one group of people in a “house of study,” who seek meaning through constant reading of an unnamed but easily identifiable text. Annamae, the protagonist in Fro, lives in contemporary Manhattan with her widowed mother and older brother. Among the constants in her life are her forthright grandmother and the delightfully quirky Rav Harriet, who teaches her about Torah and helps her to understand her place in the world. Annamae, like Ani, is on a quest for some kind of meaning, which she pursues through books and art.

Despite their different settings, Ani and Annamae’s stories echo each other, right down to the chapter titles, some of which are identical. But rather than being redundant, the stories illuminate each other in a way that makes you want to reread the book as soon as you’ve finished reading the second half—regardless of which half that was.

The author of six previous novels and five books of nonfiction, Cohen initially set out to write about the Torah study group she’d joined at her new shul, Temple Beth Zion in Brookline, MA. But when she learned that some group members were uncomfortable with the idea of a book, she dropped the project. In a conversation with Moment, Cohen talked about what she ended up writing instead—a novel in which Torah study is an oblique but ubiquitous theme. We talked about her own Torah study, her protagonists and how a Kafka parable worked its way into the novel.

Because your dad was a very secular Jew and your mom wasn’t Jewish, going to synagogue was never a part of your life growing up. What led you to join a congregation when you were in your mid-forties?

My whole life I have felt a sense of something I don’t have words for—as the girls do in To & Fro. A couple of years after the death of my mother, I began to read about Buddhist thought and Christian thought. I was interested in spirituality and theology of various kinds, but then at some point I thought, “Hey, my name is Leah Hager Cohen. How much more Jewish can I get? Maybe I can turn that curiosity to Judaism and Jewish writers and thinkers and philosophers.” And that drew me to want to experience Judaism in a community in a shul and, for the first time in my life, to study Torah.

How did you go from a nonfiction book about Torah study to To & Fro?

It was not a conscious decision, “Oh, I’ll just transpose the inspiration into a novel.” It was just that in the wake of this project that I had undertaken and abandoned, I found myself waiting to receive some kind of “message from the universe” about the next creative undertaking, and I found myself inspired by this Kafka parable about a man who is summoned by a bugle no one else can hear and sets off on what he knows will be “a truly immense journey.”

Did Kafka study Torah?

I don’t know. I do know that he became interested in studying Judaism and Hebrew. But in Jewish tradition, as I understand it, commentary may pluck from all kinds of sources and put them into conversation with each other. To & Fro is following that tradition by plucking this parable from Kafka and putting it in conversation with various other Jewish texts.

Whose story did you write first?

I began with Ani, and I would say maybe 50 pages in I hit a wall. I sort of gave up for several months, and then I found myself, one day, beginning to sketch out little snippets of what turned out to be Annamae’s story. I didn’t even know at that point if these were going to fit together. I was just writing, without a master plan. And slowly I began to think, these stories and these young protagonists are in relationship to each other. I began to go back and write more of Ani’s story, and I’d go back and forth between Ani and Annamae. I began to feel that not only were they in relationship to each other, they were reaching toward each other, each without knowing the other was there. That’s when it came to me, the unusual form for the book. I was initially resistant because I didn’t want to do anything gimmicky. But it was the book itself that seemed to be suggesting that this was how it had to be in order to be true to its essence. This is the right way for the physical object, the book, to fit together.

How did you keep things straight so that the two girls’ stories remained distinct?

I like closing my eyes and feeling my way with my fingertips and trying to trust or have faith that things will come together as they’re meant to come together. I had a dim sense of it, but mostly I was operating on a more intuitive level, willing myself into a space where the things that needed to meet would meet. The book’s not like a riddle that’s meant to be solved, any more than the Torah is. The Torah is something we can come back to and mine for fullness our whole lives. We’ll never reach a point where we say, “I get it! I’ve solved the mystery of the Torah!”

You’ve said you modeled the Ani plot in part on the story of Hagar and Ishmael from Genesis—she’s cast out by her father and his second wife— which is a pretty disturbing story when you think of it. What made you want to reference it?

My sympathies are with Hagar and Ishmael—I find Sarah and Abraham’s actions in that story deeply problematic. But something that I love about Torah study is that we don’t shy away from things we struggle with in the text. I’ve learned to value that our religious texts are full of difficult and sometimes ugly stuff as well as beautiful stuff, because that feels like a more relevant, useful, living and breathing accompaniment to the experience of life than a text that’s all perfection. Because after all, which one is more like the experience of living?

Ani and Annamae are fiercely independent, but sometimes, especially with Ani, I’d find myself thinking, “This could get dangerous for her. ” Yet she keeps encountering safe, caring communities.

In this day and age, what we expect when we read about a girl on the cusp of adolescence, journeying on her own, is that she’s going to be subject to predation—but this was not the story that was growing through me. How radical is that? I think there’s also merit in a story where someone has encounter after encounter with non-threatening strangers. At this moment in history, when we are so afraid of one another, there’s so much anger, and I think so much of the anger is rooted in a fear of others, a fear of strangers. I didn’t plan it this way, but in retrospect there may be something politically powerful and valuable about putting forth in the universe a narrative in which encounters with strangers yield something other than threat, aggression and violence—in which we see them yield kindness and generosity.

Debby Waldman is a freelance writer in Edmonton, Alberta, whose reviews have appeared in People, Publishers Weekly and Postmedia newspapers in Canada. You can read more of her writing at debbywaldman.substack.com.